Lisette Chavez’s Three Hail Marys, Two Our Fathers opened on San Antonio’s Second Saturday, July 9th at Provenance Gallery located at 1906 South Flores St. Provenance Gallery is located within a much larger complex. It’s a warehouse of sorts, situated around a railroad crossing, full of other gallery spaces and artists’ studios opened to the public. I drove up solely for the exhibition. The trip, I’m excited to say, was well worth my time and energy, the drive from Corpus Christi being about two or more hours in length. I was rewarded with rhinestones, glamour, glimmer, guilt, and many likenesses of some people’s lord and savior, the one and only, Jesus Christ.

The title of the exhibition is probably the best place to begin. The title is derived from Chavez’s first confession, an important occasion for any young Catholic, the entirety of which was camped in anxious lies. The story she related to me in our phone interview was quintessentially riddled with guilty jitters of an apostate Catholic. She waited until the last date available to make her first confession that would still allow her to enroll in the classes children must take before their first communion. First confession, like first communion, is a rite of passage that one’s family anticipates and before which there is a lot of pressure, hand wringing, and desperation with regards to selfhood and faith. She sat anxiously in the rigid pew next to her mother, a central figure in Chavez’s Catholic quandry. The priest let the line know that he would take two more confessions before calling it a day. Her anxiety surged, turning over adequate sins in her mind, as her mother explained that she was going to go whether she liked it or not, whether their was a line in front of them or not. When a starchy old woman exited the booth, Chavez’s mom gave her the ultimatum of “do this now,” that only mothers can deliver. She cut the line, and went forth into the religious darkness of confession. Chavez told me that the three sins she confessed were all lies. The most noteworthy is perhaps that she had talked back to her mother…once. Reportedly, she talked back all the time. The other two sins were equally small, believable but invented. The penance given was Three Hail Marys, Two Our Fathers, hence the title of the exhibition. It is small, but the weight imposed by the lie becomes evident when one consider the scope of Chavez’ oeuvre.

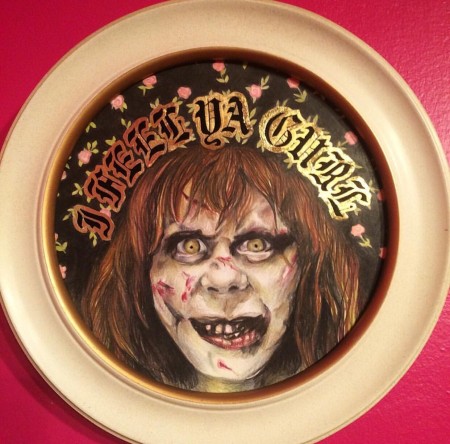

Chavez’s work deals with identity and how hers is intimately entangled with her Catholic upbringing. Catholicism and Chavez’s complicated relationship with her family and their religious dogma has been the source of heavy consternation throughout her artistic maturation and emergence. This confusion is exemplified by one of the most hilarious drawings on display. Linda Blair’s likeness from The Exorcist is faithfully rendered, her face aglow with Satanic lunacy. The words “I Feel Ya Gurl,” are drawn around here in a typeface that references both illuminated manuscript and lyricisms of the barrio. The drawing specifically references Chavez’s initial reaction to the cult horror classic whereupon viewing she felt she could identify with Blair’s character, Regan.

Provenance gallery is a small room nestled deep inside the chasm of the 1906 complex and seems to have provided a more than appropriate venue for Chavez’s work. The space feels quite like a tiny chapel with Chavez’s work installed. It’s an annex of sorts, which does not diminish the work on display whatsoever. On the contrary, the work and viewing experience are concentrated and intensified. The experience was quite like visiting a relic or sacred cite of pilgrimage. The artist painted the walls and ceilings with a color I’ll call princess pink. The candy walls and work glowed with invitation. The center of the gallery was anchored with a small section of altar. The altar’s cushioning was of fine red velvet emblazoned with text written in rhinestones: The higher cushion reads “Sorry,” the bottom cushion reads “Not Sorry.” This centerpiece evokes the dichotomy of Chavez’s religious character. The walls surrounding the altar are frenzied and full, hung with every type of devotional chalkware you might imagine. Busts of the virgin, crucifixes, drawn and appropriated images of Jesus, are bejeweled with glitter, rhinestones, and craft store shimmer. These religious affects are interspersed with tender sacrileges that are both vulnerable in honesty and keenly sexual in their export. Small photoreal drawings of condoms, erect and flaccid penises, crying eyes, a fetal skull, infected pink eyes, razor blades, and small textual confessions are framed in gaudy thrift store moldings. Rosaries are draped like foliage around the meticulously bedazzled cluster frenzy and the entire installation reads like a brutally honest teenage confession that would burn the ears of any priests worth their salt. Some of the text pieces provide provocatively informative phraseologies like: “When are we going to have the sex talk?” “I’ve read the Satanic Bible, but not the holy one,” “Believe in God, Believe in the Devil,” “While you prayed the rosary, I thought about all the times you’ve hurt my family,” “She fucks strangers on Saturday night and goes to church on Sundays,” “We only dated because you looked like Satan,” “He whistled and said ‘Hey baby,’ I was six, but I prayed for him to die,” “More crosses and more Jesus’ won’t help you or me,” and “I said I’d pray for you, but I didn’t.” All of these phrases are personal and function quite like confessions.

The content and construction of Chavez’s work is complicated and fiercely multidimensional. I was surprised to find out that despite the overtly irreverent nature of her work Chavez still goes to church, still prays, and still sort of believes in God. Chavez goes to church because she loves the intensity, the catharsis, and the ritual aspect. She loves the sound of people praying. She’s somewhat of a Catholic voyeur. She told me that when she sees an especially unique statue of the lamb of God she gets very excited. She still keeps a crucifix hung above the door of her studio. She also told me that she finds it incredibly hard to believe in God when there is so much tragedy in the world. She cannot believe that so much pain is supposed to teach us something. So while Chavez isn’t the pinnacle of piety and may not even believe in God all the time, it’s clear that her religion, or that of her family is deeply entangled with her identity, probably inseparably so.

The merit of Chavez’s work is in its personal vulnerability. The familiarity of religious iconography is used digestively to lubricate intensely intimate disclosures regarding sexuality and selfhood and how their pursuit interrelates with religious doctrine and belief. In Chavez’s case the two would seem to be at odds.

The statues of Jesus and Mary are hung with rosary and encrusted with rhinestones and glittery ephemera, which simultaneously evoke the sacrosanct and the greasy residue of popular culture. The titles of these pieces refer to them as infected. The rhinestones cover the faces of Jesus and Mary like boils, problematizing their mass production and posing the question of whether we love them because of who they depict or because of their popular proliferation. The many drawings of eyes, all intensely glaring, convey the voyeurism of Chavez’s own religious spectatorship and the intensity of the watchful eyes of God, while the infected pink eyes pose a question of purity. “Am I good enough?” Chavez’s installation is a sort of confession against the sacrament, a joyful misstep and paradoxical dance through the questions of Catholic faith. It is a raging against the self censorship that Chavez realized she was self inflicting during her MA when she began drawing grotesque images of dicks and two-headed cats out of frustration. She realized she was self conscious, and that this sentiment was born out of religious origins. This body of work is responsive to a need for vulnerability and honesty concerning the guilt rendering voice of her mother: A voice that haunted her artistic output, that was perpetually ringing in her ears. This voice and its effect is a personal phenomena that Chavez has been entertaining for several years now, beginning with her master’s thesis. The artist says that this will likely be the last time she shows this body of work which has already or is at least nearing its conclusion. Inasmuch as Chavez’s work exposes her conflict with her Catholic upbringing and a disdain for many of the rules’ infringements on personal sovereignty, she contends that she will never separate from the church, that to do so for her would be impossible. Interestingly Chavez let me know that things have gotten easier for her since she started making this work. That audiences have been receptive and in this she has found it easier to continue purporting internal authenticity regarding her religious experience.

The aesthetic purport of Chavez’s work is closely akin to those who’ve made a habit out of appropriating the mundane object culture of thrift stores. Chavez’s work may remind viewers of Nick Cave, Trenton Doyle Hancock, Raul De Nieves, and Mike Kelley; Judy Chicago also comes to mind. Chavez’s work is celebratory and confrontational too. Her use of rhinestones and other elements of shimmer and glimmer reference her obsession with fashion to the tune of Balmain and Discount Universe. The irreverence of Francis Bacon is also there. The sexualization of Jesus Christ and its impossibility is palpable. This is perhaps what comes across most when viewing Chavez’s work. It’s what I would describe as the impeccable humor of personal paradox and the discomfort therein. Chavez’s journey it seems has been a painful secret that’s now transformed into a touchstone of divine comedy in our mortal coil. Her painful secret, however, absolves her of her guilt, and frees her from judgment. She feels that so long as she is relating a truth that’s wholly personal then no one can tell her it isn’t valid. Chavez feels like this work is her direct line of communication with God, if He’s listening. Her expression of guilt is remarkable, its permutations striking chords of consideration across the boundaries and intersections of American Pop culture. Her transgressions are battling both personal belief and institutional axiom as they exist within and without as well as familialy. This is where Chavez’s work derives its vocal breadth. The pleasures of sexual humor, and surfaces of elevated visual felicity that deliver a divine fleshiness amidst a krafty, technicolored, sparklegasm are all just triumphal icings of a cake that’s swimming with careful content all through its funfetti innards.