Summerfair began in 1968, more than fifty years ago, as something of a street fair that spilled over into all the available spaces in Mt. Adams. It became more professionalized (juries and the like) in its first move to Coney Island, and then in the 1970s it moved to the Riverfront area, which is where I first encountered it. I have a vivid memory of an artist who was assigned a space out on the exposed and shadeless Plaza who built herself a shelter out of her own paintings to give her some relief from the sun and the heat. In 1985, Summerfair returned to Coney to stay. The roots of the Weston show go back to 1981, when Summerfair brought in jurors to award $3000 prizes (recently increased to $5000) to a small handful of exhibitors per year, each of whom must live within a forty-mile radius of Cincinnati. The current Weston show, postponed twice because of Covid, honors three years of winners.

Across the street and down the block from the Weston, the Contemporary Arts Center is featuring a show called “The Regional,” and it’s interesting to compare the two exhibits’ ideas about artwork from the region. To be sure, the CAC show is intended from the start to be far more sweeping, displaying the work of 23 artists from 14 cities across the greater Midwest. The show at the CAC was heavily and explicitly political. Its focus was on stinging critiques of racism and sexism, and it freely mined recent and no-so-recent history to develop a commentary on capitalism, colonialism, the environment, and immigration.

By contrast, the artists selected for the Summerfair show tend to be more interested in issues stemming from the individual. Its focus might be said to be on psychological issues, the body, identity and the forces that blur it. The works tended to turn us inwards rather than outwards. Though the judges were hardly apolitical in their decisions, their tastes tended to run more towards the local and the personal. There is nothing I could see at the Weston show that reflected on race or international conflicts. Both shows had some interest in edgy gender issues, sometimes explicit and sometimes implicit. There were some deeply analytic strains in the CAC show—how did things get to be this way?–while the Summerfair show tended to be more interested in the effects, rather than the causes: how do these awkwardnesses in our culture make us feel? The Summerfair show at least glanced at the personal dislocations caused by the pandemic. And the Summerfair show seemed to be considerably more interested in the materials from which art is made and proudly showed off the absolutely remarkable level of craft in the artists’ works.

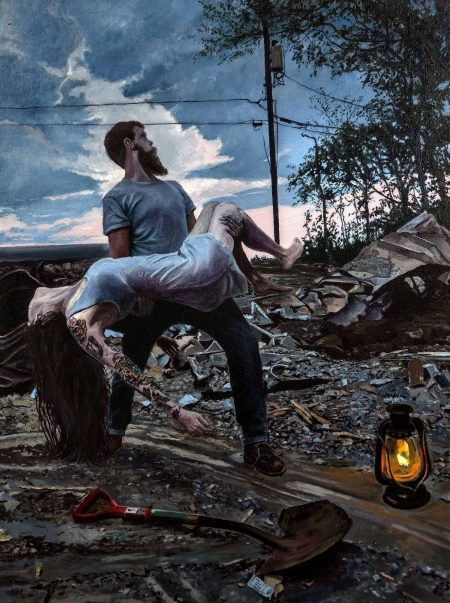

We can get a sense of the psychological richness of the Summerfair show by looking at the work of Kevin Muente (for whom this was his third Summerfair award). In “Act of Nature “ (2018), a bearded man is carrying off a dead or unconscious woman. It might be a rescue; it might be an abduction. He could be about to roar, like King Kong making off with Fay Wray. Muente clearly wants to evoke a narrative, but the story the painting suggests is by no means clear. He carries her through a field of debris. Has a flood just receded or a tornado just whirled through or a plane just crashed—or is this just what man does to nature? Close to his feet are, presumably, the tools of his trade or rescue—a shovel and a kerosene lantern. But he doesn’t have, of course, enough hands to have been carrying everything. They sit on either side of a wet gully like props. It is not at all clear how he got here—we have to be content with what we see. In his Artist Statement, Muente calls his paintings “cinematic,” and that seems very fair: we are drawn to the drama he depicts, but also remain distant from it. The painting could be a very effective poster to a movie.

The male figure is captured mid-stride and is frozen in his pose. There is something related to Hellenistic statuary about Muente’s figures: they are caught in a moment of suspended action. The man’s head is sharply turned off to one side. Has he heard something that we can’t see or is he averting his eyes from us, or from the whole scene? As in a number of his paintings—“Family Portrait” (2019) is another excellent example—Muente seems to asking questions about just what constitutes a “pose.” It is something that borders on the extreme; it is restful for neither the figure nor the observer, which is part of what contributes to their psychological richness. Though he exposes all his characters, if we may call them that, to the outdoors, there is little to make anyone feel at home in nature. Even his sleeping figures, like the girl in “Sleep of Reason” (2019), are mysterious.

Tyler Griese’s paintings are also cinematic in their way, encapsulating moments of drama, but he tends to see this as a norm of our world, the way we live our lives, not an extreme that can be played with. In his Artist Statement, Griese proposes that his interests are in constructing “an allegory of titanic human narrative of instability and vulnerability.” His paintings are haunted by a sense of imminence: he is interested in capturing the moment just before something is about to happen. In “The Past is Close Behind” (2019), a female figure is asleep (or unconscious?) sprawled out in the foreground on a chair in what looks like the family room of a suburban house. Two partly-clad figures seem to be tip-toeing out, apparently swiping things off the bar top on their way. It feels like a depiction of false friendship in which the central figure is not even aware of her vulnerability; she has been placed in the middle of a drama she can’t see. She will—we hope—wake up at some point, but will find herself betrayed and abandoned. Griese sets his paintings in a suburban world where one’s attributes of wealth create no security. In “Wistful Daydream” (2019) he paints a central figure who is surrounded by signs of middle class comfort but has no access to them: a smart phone, a drink, perhaps members of her family. To me, she does not look wistful in the least, but rather just about to fully realize something horrible. A moment of revelation is very close at hand, and neither we nor the painting’s subject is going to like it.

Not all the paintings in the Weston show are about drama, or melodrama. Michelle Heimann’s work, for instance, as she writes in her Artist Statement, is about her “desire to find and create ‘comfort.’” That need for comfort, she explains, is in direct response to the pandemic; she is one of the few artists to respond, either directly or indirectly, to life under Covid. Like most of us, Heimann found herself with no alternative but to take her imaginative life indoors. The work she is showing at the Weston are all from a series she calls “The Interiors.” I take these paintings to be paintings of largely imaginary rooms (how many rooms can one house have?), but I could be wrong. The paintings themselves are eye-catching—they have some of the color schemes of Matisse and some of the obsession with household details that you might see in a Vuillard. She seeks pleasure in the magic of these rooms. A work like “The Curtains” (2021) goes out of its way to find a scheme of symmetry to help us find our true place in this world. Heimann is content to bring nothing into too tight a focus; we are always aware that we are witnessing a world made of paint. Unlike a Vuillard, there are few signs of active human occupancy in these works. The paintings seem designed to capture the still lifes in which we live, a refreshingly artificial world in which we can take shelter.

Mark Wiesner’s wall pieces take unconventional materials and masterfully transform them. He starts with what he calls “remnants or scraps” of cardboard, weaving and painting them until they look more like glittering metal. He displays both the smooth surfaces of the cardboard and the corrugated ones, giving his pieces rich and startling rhythms. While his work with the materials he has chosen makes his pieces seem more sturdy, even monumental, his titles make them seem more tenuous and fleeting, as if he’s capturing a passing moment of thought over which he has no control. The most recognizable shape he exhibits here is a mole’s eye view of a sheaf of grass, impenetrable in some places and airy in others, which he has titled “As Sleep Descends It Rustles Through the Grass and Ties My Thoughts into Knots That Then Unravel” (2021). It may be that Wiesner is asking his title to do too much of the work here, but it does start to suggest that the piece is a way to capture time and movement, and that he himself is and isn’t like the grass he depicts. Holding the wall at the bottom of the stairs is another Wiesner piece, this one an abstraction in purple and black, perhaps a bit like a bruise. Somewhere between an elegant puzzle and a highly organized scribble, it makes you unsure of where it begins and where it ends. Once again, the sculpture’s essential monumentality is loosened by the title: “The World Felt Tenuous as Though One String Could Be Pulled and It Would All Unravel” (2019). The title suggests that this puzzle is not impossible to solve; unlike the Gordian knot, a slight tug could reduce its complex twists into a simple line. It leaves us to wonder whether that would be a good thing or not.

I had trouble taking my eyes off Lisa Merida-Paytes’s work, whether it was her wall pieces or the sixteen-foot tall monumental installation on the upper floor hanging from the ceiling. These powerful pieces are made almost entirely of starched paper enriched frequently by a delicate staining of brown and blue. The paper is sometimes torn and sometimes cut and then woven together in a way that I would like to have been able to witness but whose net effect is a mixture of linear and free-form, smooth and rough, tightly contained and on the verge of flying apart. Regardless of the scale, the work seems deeply biological–and not necessarily in reassuring ways. These are the kinds of shapes out of which the innards of living things are made. Merida-Paytes’s ferocious imitations of living elements are both monumental and disturbing. Confronting what you’re made of isn’t going to be easy.

In her Artist Statement, Merida-Paytes orients us quickly about the biographical aspects of her work: her father ran a “taxidermist/slaughterhouse business.” Bodies and parts of bodies constitute the language out of which she makes her statements and asks her questions which focus, as she goes on to say, on matters about “growth and decay.” “Anamorphosis Series: Pulp V” (2021) helps us see the range of her visual language. The overall shape suggests a paisley (as does another of her wall pieces, “Anamorphosis Series: Wall Flux”), with sweeping curves coming together to a sort of a point holding things together. The more linear pieces of paper suggest ribs or some other way of supporting the sculpture’s shapeliness. The smaller torn pieces almost coalesce into flowers, though not quite. If these are our innards, we are busy down there. In “Pulp V,” she has added literal depth to the whole by extending a sort of porch into which we can peer. The hanging has been masterfully lit by the installers because we are able to see inside this extension as if we had our noses pressed up to a fence overlooking a calming garden. Inside the dappled light, things are gentler and cozier, though still surrounded by the more rough and raw shapes of the outside shell.

Jeweler Christina Baitz-Brandewie work also calls the body to mind as she crafts what she calls “sensuous forms of body adornment.” Her gemstone work was perfectly striking, but I found myself particularly drawn to the half dozen or so bracelets that were on display. They are from what she calls her “Fabric” series because of the frequently intensely decorated nature of their surfaces. The most arresting of these bracelets are made of strips of metal that have been bent into rows of concave or convex partial circles, making them both airy and yet architectural as well. There are curves within curves, sometimes layered with bracelets that encompass other bracelets. On some of the most complex of these, Baitz-Brandewie uses small pearls as punctuation, sometimes where they are visible, and sometimes, most strikingly, putting the pearls on the inside of the bracelet where they cannot be seen; all we see on these are the fastenings, which equate the invisible pearls with rivets, the decorative merging with the functional. I can’t speak for the comfort of these pieces on one’s wrist, but they seem particularly daring. On the one hand, they have value that is hidden from the viewer and gives the pieces a kind of literal inner life. The whole piece exists only in the mind of the wearer, making the bracelet’s total into a kind of shared secret.

Amanda Curreri’s work is rooted in her conviction that the roots of today’s communication can be found in the “woven structures” in the distant history long before electronics. With straightforward collages, whose unfinished edges of loose strings and threads often call attention to the process of their creation, she draws us back to the simplicity of how we share our thoughts and feelings. These works connect us to our “hxstories,” to use Curreri’s term, and in particular to stretches of the past that have excluded the unspoken stories of LGBTQ+ people. In many pieces, she mines this history by including emblems of “Dinah,” an image she has taken from the cover of a 1980 issue of the lesbian newsletter Dinah, which enjoyed a more than twenty year run in Cincinnati. The Dinah image is a female breast, sometimes used singularly and sometimes in multiples, calling to our attention an emblem of female identity and also of the community happy to share it as a code. It also keeps us in mind of the ghost of the human body, the body referred to but not present. Perhaps Curreri’s most striking piece is the “O.H. Coat” (2019) (“O. H.” is short, she tells us for both “Ohio” and for Obergefell and Hodges) set out to hang on display, itself a ghost of the body. Embellished with some chaste but striking embellishments, the inner lining consists of multiple versions of the Dinah image in many different colors. Like some of Baitz-Brandewie’s bracelets, only the wearer has a grasp of the complete design and power.

Marsha Karagheusian is also interested in feminist communication and sees her painted clay tiles of nude dancers (45 dancers in 8 wall pieces, in all) as connecting to “a 10,000-year tradition” of ceramics. Each set of dancers is mounted as panels in one sort of antique window or doorframe or other, replacing the glass or wooden rectangles. I would have been interested in how this mounting directs our thinking towards the domestic environment as either a complement or a contrast. While the painting on many of the panels was striking, I saw the figures as tied up in their (often similar) gestures, rather than being part of what Karagheusian calls their “opposing cultural narratives.”

Summerfair is designed to attract a wide range of artists and audiences with a great many different interests, and so it is highly likely that not everything worthy of recognition will appeal to everyone. At the risk of being thought humorless, I found I was not on the same wavelength as Anne Huddleston, who covers fiberglass animals with mosaic skins of glass, stones, and other collaged objects. I was more drawn to Sarah Miller’s felted sculptured beings, some plant-like, some animal-like, and some a mix of the two. She sees them as small rebellions against the world’s (and my) excess seriousness. As Miller writes in her Artist Statement, “There is a place I imagine, it is wild and growing, a tangled forest that exists outside of time….It is here that I envision a joyful menagerie of woodland characters banding together…to celebrate and commiserate….” I appreciate that in both these artists’ cases, they imagine themselves creating fresh new worlds, designed to surprise us and change our perspective on what is and isn’t possible as we settle deeper and deeper into our own.

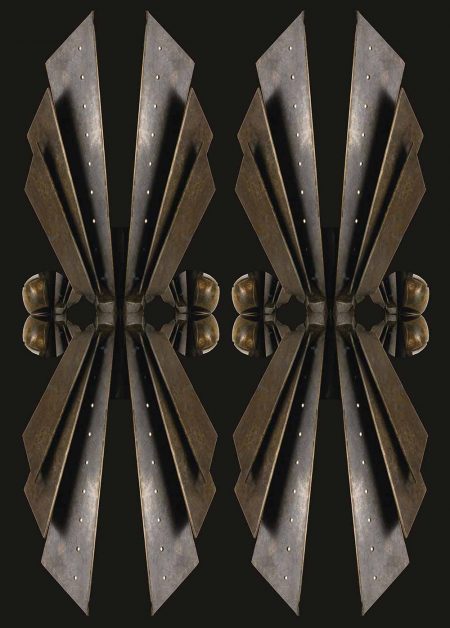

Stacey Dolen also deals in the transformation of materials. She starts with a brass sculpture which she photographs, and then manipulates the images with Photoshop. It is hard to say what we are looking at as she allows the one piece to generate new ones. Sometimes they look like other sculptures. At other times, her influences (“of Biomorphism an Italian Futurism”) enrich and complicate our sense of what we’re seeing. They could be remarkable plants or examples of the sometimes airy, sometimes brutal work of Italian modernism. Sometimes they seem richly three-dimensional and sometimes they seem flat, an effect magnified by printing the end image on polished aluminum. Part of the drama of her work is how the images both retain and sacrifice their sculptural origins. Some look like we’re seeing a picture taken through a kaleidoscope, and some (as in “Twin Forms” [2017]) look like modern adaptations of medieval weaponry. The spirit of recycling shapes the whole project, and there is a pleasure in recognizing elements that we have seen before, now “digitally resculpted” into a whole other thing that requires our awe and attention. But then other versions look more like egg sacs and other sea-born forms washed up on the beach after a blowy day—evidence of such an abundance of life that it may be hard to take, as we can feel in front of Medina-Paytes’s pieces. Together, in Dolen’s words, they produce the effect of “inviolate, armored biology that can withstand the hostilities of our increasingly toxic environment.”

This brings us back to ways that the Summerfair show and the CAC’s “Regional” show share concerns about the world around us. Alice Pixley Young’s pieces depict nature as we have colonized it, and some of the ways that nature resists. Young states that she has drawn upon a wide range of inspirations, “from the Hudson River School to Land Arts.” Each of these extremes is an example of the landscape that has been touched by humans. Indeed, they raise the question of whether it is possible for humans to see an untouched landscape: to look is already to have touched. Like Merida-Paytes, Young makes monumental objects from mere paper. The opaque, black roofing paper Young uses evokes the 19th century vogue for silhouettes, and helps call the gothic to mind. In a piece like “Lit (Broken Utility)” (2019), she depicts a power line becoming overwhelmed with vines. Cross country power lines have long been seen as potentially anthropomorphic, and stand in rows as effigies to the human; they are our version, perhaps, of the sculptures on Easter Island. In “Lit,” the steady triumph of the plant world is both lyrical and reminiscent of many of our favorite horror stories in which the human is defeated by the vegetative. We build statues to ourselves out in the wilder realm of nature, but it is a competition that nature will win. Will we be ready to pay the cost of achieving harmony with the world around us?

We make things that are ready to be beautiful or scary; Merida-Paytes’s homages to the elements that make up life and Dolen’s manipulated photographs come to mind here as well. Young surrounds “Lit” with a rope of pink LED lighting that only enriches these issues. It could be seen as a sort of cartouche, giving a name for a thing, or the form like a tombstone, showing how things end. It might serve to remind us that the electricity came through somehow, regardless. Do we read it as a lasso, man’s boastful claim of victory showing that he can control whatever nature throws at him (or glides unstoppably up his constructed legs)? Or is it designed to make a mockery of humankind’s celebrations, affirming that we just don’t get it?

Though the gallery’s photograph of this piece unfortunately erases it: when you look at “Lit” in person, you would see a rich interlaced network of shadows that the elements of the piece cast against the wall. But this is probably not what the artist had hoped for. In her Artist Statement, Young suggests that we should be seeing ourselves, in that the work is “activated/implicated by the viewer’s own shadows.” This would, of course, vastly enrich the political reach of the work—to see ourselves, our psychological complexities reduced to silhouettes, as part of the world represented in front of us. It would have been a handsome way to have combined the political and the psychological.

“Summerfair Select” at the Weston is open until April 3.

–Jonathan Kamholtz