Make or Break: Recent Work by Oscar Guerra opened at Silkwörm on July 9th on San Antonio’s Second Saturday and featured a healthy selection of Guerra’s paintings and collage works. Inasmuch as there are paintings and collages, Guerra thinks of almost everything he does as part of the same process which he considers to be drawing. Truly it is. The hand is the anchor to Guerra’s wily sails that take inspirational direction from winds of environmentally dependent compass points. The gallery in which his works are hung is a narrow corridor within the much larger complex, which features an ample offering of gallery spaces and artists’ studios open to the public. I would encourage anyone to visit the complex as it is an exciting venue that seems to garner substantial local support as well as audiences from the surrounding area as far away as Austin. With regards to the curating I was pleasantly surprised by this selection of work, none of which I had seen before in person.

The exhibition, from the viewer’s standpoint, is a compilation that plays a sort of transchronological mixtape of Guerra’s flow exemplifying explosions, interstices, and stones rolled through the process and its gunk. In order these would be, the Cameo Series, a series of collages on baseball cards, and a pair of sculptural painting assemblages.

Guerra’s works in this exhibit are evocative of a DIY ethos and a fluxing material limitation dependent on geography, finances, frustration, and origins. When Guerra first began making art it was always collage, simply because he could make something out of otherwise mundane ephemera. When Oscar began making stuff he did not have the savvy nor the access to materials traditionally considered appropriate to the fine art endeavor. In this way some of Guerra’s painting is its own brand of rough hewn human experience shot like a beam of bop through the prism of human experience.

Talking with him was extremely telling, and very natural. Inasmuch as Guerra’s work happens quickly, and carries a brutal compulsion comparable to the vibe of some visionary and outsider artists, everything is terribly intentional, well read, and distinctly choice driven. Guerra makes choices regarding the direction of his work bodies based on where he’s at in his life, both literally and maybe existentially also. If the place he’s living in is tiny in the midst of a convulsive metropolitan environment baked by the Texas sun, like San Antonio, that’s absolutely going to make face in the work. Much of his work he says is still Corpus Christi, where he earned his MFA, and which he still considers to be his home of returning in many ways. The work is self-conversational. The echoes of Guerra’s hand-styles ask questions of brushed-swoops, to which spliced-collaged-headlines answer, only to be stifled by the intersection of a meticulously paint laden fragment of pasted cardboard. Rules are established within the process only to be later broken, remade, and then disappeared all together. This kinetic energy is what comes across when you stand in front of Guerra’s work, and it feels like jazz, it’s driven by impulse and improvisation. It is a lot of fun to look at.

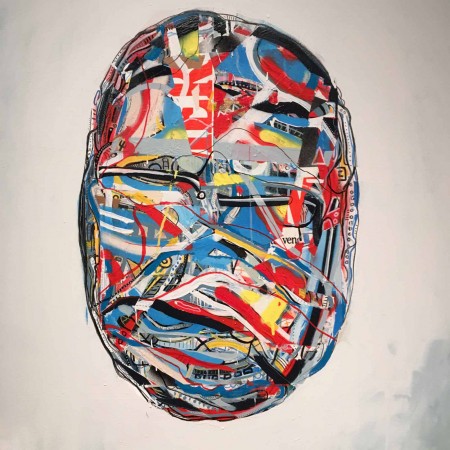

The implementation of collaged elements in Guerra’s work supplies an industrial feel that evokes the modern age, and the frenetic speed of contemporary visual culture, and also the personality of South Texas, which to put it lightly is a gritty place. The pulse of the street, of the commonplace, and everyday hustle is palpable in Guerra’s surfaces, wrought of a heavy and swift hand. Compulsion is tangible in the rough surfaces of Guerra’s paintings. Three of the larger paintings in this exhibition feature excerpts from Guerra’s “Cameo Series” which abstract the human head with riddling blue line, and swerving red flourishes, all amuck glue and painterly detritus. They look quite like the Olmec heads, sculpted from the page in a sense; they boast a tactile quality that increases their visual weight.

Opposite the wall hung with the bravado cameos was a series of nearly twenty collaged drawings on baseball cards, which provided a sectional staccato foil to the weighty cameos. This series of works speaks to the side of Guerra’s process that is limited by lack of studio space and enabled by his vast collection of ephemeral materials. Guerra is driven by the necessity for adaptation and this is perhaps his work’s survival mechanism, as it would seem that nothing could ever stop his hand.

The collages are all done on baseball cards and they are titled through a system of chance where names of Guerra’s favorite songs and pop songs from the card’s era were drawn from a hat alongside the player’s names. The results produced titles like Ghost Bitch Canseco, Lodi Dodi Hardaway, Lucky Star Holyfield, Blood Duster Duran, and Bo Rump Shaker Jackson. The collages were framed without glass, which increased their tactility. About these works, as well as with regards to most everything he makes, Guerra says that he works cyclically in series. He switches back and forth between the interstitial periods of making that are dominated by collage, and investigatory bodies of work that are more their own thing. The Cameo Series is one such body of work. The two spaces of working find similarity in their limits. Guerra says that when he hits on something he runs with it until his legs give way to exhaustion. He masticates ideas until they provide no more food for thought. He works ideas to exhaustion and then moves into the next space of working. The texture of the work echoes his words. Their surfaces have the patina of experiment all over them; like jazz musicians play different solos for every live performance of the same song, Guerra’s conclusions are drawn through the heavy fabric of trial and error.

The final topic of discussion for this exhibition is a pair of works hung on a small outcropping of wall close in proximity to the collages. The pair of works are assemblages, drawings, paintings, composed of studio detritus accrued over the course of four or five years. Painting props, scraps and other elements are drawn together in a talismanic curating of processional fragments. The slowness of these objects’ identities is what makes them special. They have a certain maturity to them and as a physical remnant they tie the work together well.