A few weeks ago I made my first visit to the Contemporary Arts Center since the pandemic’s beginning. After holding up my phone so the visitor staff could scan the QR code of my timed entry ticket, I stepped over to the lobby in order to behold the Brussels-based Marjolijn Dijkman’s newly commissioned wallpaper. Earthing Discharge is the latest installation to occupy the vitally important wall space dominating the CAC lobby. Following Kahlil Robert Irving’s Ground Water From Screen Falls [(Collaged Media + Midwest STREET)] (reviewed in the June 2020 issue of Aeqai), it is the second wallpaper commission organized by CAC Senior Curator Amara Antilla.

Spanning the lobby’s entire 40-foot wall, Earthing Discharge is a printed photo collage showing small electronic components found in personal electronic devices tumbling alongside lumps of rare minerals extracted from the earth for technology and energy use applications. Dijkman photographed these objects through conductive glass while subjecting them to high voltage electricity. Through this process, each object (enlarged to comparatively monumental scale) is transformed into a Tesla coil illuminated by its own corona discharge. Blue and violet electricity spidering into the inky void, it’s hard not to think of microbial life, or planetary-scale spaceships. Printed on slightly glossy adhesive vinyl, late afternoon sunlight slants from the lobby windows, layering orange onto the wall’s deep blue.

Dijkman’s research-driven practice is often concerned with showing otherwise invisible phenomena, like electricity and smartphone circuitry, and, in doing so, exploring an ethics of representation in bio- and techno-social contexts. For instance, in a 2018 collaboration with Toril Johannsen and composer Henry Vega, Dijkman created a narrative film made entirely from footage of microbial life found in brackish waters (the rise of which being metonymic for the Anthropocene). Reclaiming Vision deliberately anthropomorphizes these microbial forms, inviting the viewer to empathize with otherwise invisible lifeforms. Dijkman and Johannsen seem here to be after something like philosopher Timothy Morton’s “ecological thought,” which contemplates all life as a “vast mesh of interconnection” with no center, human or otherwise.[1]

Rather than brackish waters and living microbes, Earthing Discharge is the convergence of research into the history of electricity and ongoing documentation of a lithium mine under development in the Democratic Republic of Congo. As part of an interdisciplinary research project On-Trade-Off, Dijkman and others seek to call attention to the environmental and economic implications of extracting rare earths for use in “green” technologies. As an essential component of high-capacity power cells manufactured by Tesla for use in technologies marketed as planet-saving, lithium becomes a charged metaphor. Punning on the double-meaning of Tesla (Nikola contra Musk), Earthing Discharge invites us to see the invisible force that powers our smartphones as a visible, awe-inspiring force, drawing inspiration from 18th century electricians who enraptured audiences with spectacular stage demonstrations. Just as Reclaiming Vision called attention to rising sea levels, Earthing Discharge asks us to think ecologically about the subvisible, nonliving components ubiquitous in our daily lives. By visually aligning the transformation of rare and toxic materials into ubiquitous conductive commodities, and imbuing them with a kind alien life, it invites the possibility of thinking on a planetary (or ecological) scale.

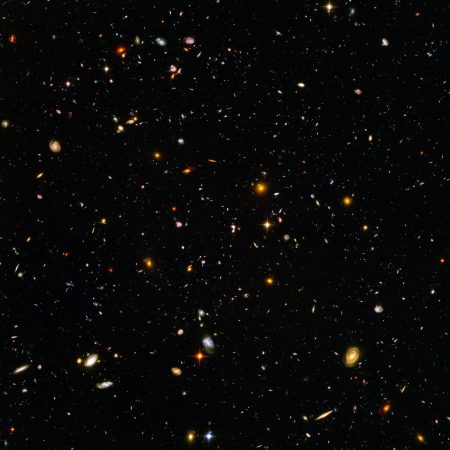

Yet this is not a journalistic project. A viewer won’t walk away more informed about the ecological hazards of lithium mines or the exploited laborers who work in them. Nor will they be presented with evidence of an environmental crisis of e-waste, the byproduct of planned obsolescence and unfettered capitalism. Per Dijkman’s own statement: “Earthing Discharge returns to this moment in time when electricity was still made visible, in contrast to today where most electrical processes are hidden from the eye and more or less taken for granted.” Consistent with that ambition, the nearest visual analog that comes to mind is the Hubble Deep Field image, in which tiny pricks of light are revealed as not stars but entire galaxies.

As with any work installed on the CAC lobby wall, scale is a crucial consideration. The lobby wall is interesting because, due to its high visibility, it operates as neither interior nor exterior. It falls in a middle zone. At least in spirit, it is the consequence of CAC architect Zaha Hadid’s “urban carpet” concept. For Hadid, who opposed the presence of artworks in the lobby (and certainly would have recoiled at such uses of its central wall), the “urban carpet” was a formal concept purely embodied in the sidewalk curving into the wall. Thankfully for us, the CAC has more recently come to understand the much richer spirit of the concept. In this broader interpretation, public and private space don’t so much curve into one another as coextend, entering into a state of superposition. Looking at Earthing Discharge, the thought enters my mind: Is the CAC lobby wall like Schrödinger’s box? Certainly its state is observer-dependent. In order for a work to succeed, it needs to make one kind of sense when viewed from across Fifth Street and another kind of sense when viewed from five feet away. In the former case, it needs to function more like an exterior mural, optimized for appreciating at a glance from the window of a passing bus. Inside, it must convey information at a different scale (unlike a mural, which loses its coherence when viewed up close). In this regard, Kahlil Robert Irving’s work succeeded, and I think Dijkman’s does, too. Returning to Timothy Morton: “The ecological thought […] involves dissolving the barrier of ‘over here’ and ‘over there,’ and more fundamentally, the metaphysical illusion of rigid, narrow boundaries between inside and outside.”[2] As viewers, we benefit greatly from Antilla’s ecological approach to this vitally important exhibition space.

In a talk earlier this year at the De Brakke Grond in Amsterdam, Dijkman’s Reclaiming Vision collaborator Toril Johannessen quoted philosopher of science Ian Hacking: “We do not in general see through a microscope; we see with one.”[3] There’s a corresponding truism with Earthing Discharge, which allows us to see with a capacitive touch screen. Although this work is configured for ocular and not tactile appreciation, the sense of touch is nonetheless implied. We touch with the screen and not through it. This maps onto the scale of the work: touch capacitive technology is scaled to the human body, specifically the finger, which taps and moves along the smooth surface. It expands and calls attention to the point of interface between both senses of the word digital.

–Steve Kemple

Marjolijn Dijkman’s Earthing Discharge was organized by Senior Curator Amara Antilla and will be on view at the Contemporary Arts Center through March 21, 2021. It was one of the many projects supported by FotoFocus in lieu of their 2020 Biennial.

Watch Marjolijn Dijkman discussing Earthing Discharge with curator Amara Antilla and On-Trade-Off collaborator Jean Katambaya Mukendi in a filmed conversation here.

[1] Timothy Morton. The Ecological Thought. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 2012. (pg. 54)

[2] Ibid. pg. 56

[3] Ian Hacking. “Do We See Through A Microscope?” Pacific Philosophical Quarterly 62, 1981 (305-322)