The Reformation had its 500th anniversary this year. A movement that changed the ways Europeans read, worshipped, traded, and slaughtered each other, it also had the potential to change the nature of art. In part, this is because the various Protestant churches that sought to reform the Catholic hegemony tended, among other things, to take the Second of the Ten Commandments to heart, the one about having no graven images. This made them, to varying degrees, iconoclasts, the idol breakers, who did selective but considerable damage to medieval statuary and paintings and shifted the ways artists in predominantly Protestant cultures practiced their trades. (Four years ago, the Dayton Art Institute had an excellent show from the Victoria and Albert Museum that traced the rise and definitive fall of English sacred carvings in alabaster from Medieval times to the Reformation.) In honor of the Reformation’s anniversary, the CAM mounted an exhibition to help us admire the taste and ambitions of two figures who lived centuries apart, Albrecht Durer and Herbert Greer French, the P&G executive, pictorialist photographer, and extraordinary collector of early prints whose extensive holdings, given to the Museum in the 1940s, form the core of the works in the show.

The title of the show is at least a bit misleading. Though one might hope to be able to see how an iconoclastic culture found and developed a new systems of pictorial language for a new age, in fact Durer’s relationship to the Reformation was circumspect at best. Though he seems to have been interested in Luther’s work and, we are told, owned a number of his pamphlets, he was also a sharp enough businessman to see that the Reformation’s attitudes towards representations of things divine could put him out of business. And while he executed, late in life, a number of engraved portraits of Luther’s advisors and followers, he also did a portrait of Cardinal Albrecht of Brandenburg, a strenuous opponent of the Reformation. Rather than helping to devise ways of making images that could be compatible with the new religious ideas and emphases, Durer devoted the final years of his career to publishing books about his theories about art.

Germany

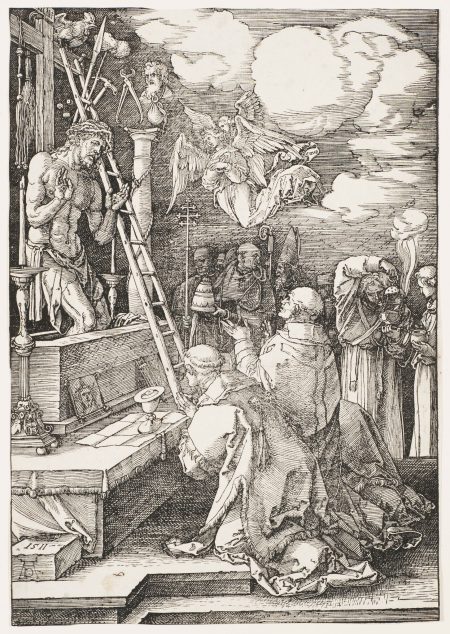

Mass of St. Gregory

1511

woodcut

Gift of Herbert Greer French

1940.219

In Durer’s mid-career woodcut “The Mass of St. Gregory” (1511), we can see what the Reformation did not look like. Gregory, a monk who had become Pope in the late 6th century, was celebrating Mass when, in response to an onlooker’s expression of skepticism about the literalness of the transubstantiation of the Eucharist, Christ Himself appeared above the altar. The vision is a gift, of sorts, for the Pope; as the caption on the wall observes, all the other men in the print seem partly or entirely distracted as Christ appears. Gregory, transfixed, can’t tear his eyes away. Some of the drama in this—and other—Durer prints is the difference between people who see things and those who don’t. If the Reformation leans towards being iconoclastic, in this visually dense woodcut, every possible image associated with Christ appears arrayed in the air: the cross, the dice, the cock, the scourge, and so on. It is as if the purpose of the print is to confirm and celebrate the importance of divine imagery; leaning up against the altar is a separate small painted image of Christ. Images clearly exist for purposes of devotion—a perspective on which the Catholic Church and the Protestant churches to follow would strongly disagree.

This print is, at its core, so non-Reformation. In other artists’ versions of this same scene, indulgences—one of Luther’s chief bête-noires—for up to thousands of years were traditionally appended to the bottom. Elsewhere in the show is a remarkable woodcut of a “Madonna and Child” (1520-25), possibly by Sebald Beham, printed on the reverse of some repurposed paper stock, but with enough red and gold paint still showing to make it clear that it was an ordinary person’s object of veneration, an altarpiece for an ordinary home. There is something cheerfully medieval about the Durer St. Gregory. Among its more “modern” elements are the particularized portraits of the people in the background—Durer virtually never failed to individualize the figures in his crowds, especially if they were male—and his interest in the floral curlicues of drapery, likely to have been influenced by his study of classical and Italian models. (It was a look Durer liked so much he often used it to show the frothy movement of water flowing around objects.)

Also more modern, perhaps, is the presence of Durer’s monogram in the body of the image. I used to think that there was something intriguingly egotistical about the Northern Renaissance need to make sure their initials were present right on the image, but the CAM show strongly suggests that it was an exercise in branding. The notes to the show tell about Durer taking time off around 1506 from his production of woodcuts to go to Italy and track down the artist who had produced copies of his Life of the Virgin (1503-1511). In the end, he not only got an injunction against the Venetian engraver Marcantonio Raimondi, but the final published book concludes with a colophon forbidding the unauthorized use of Durer’s initials—though not necessarily the images themselves—a ban reportedly backed up by Emperor Maximilian.

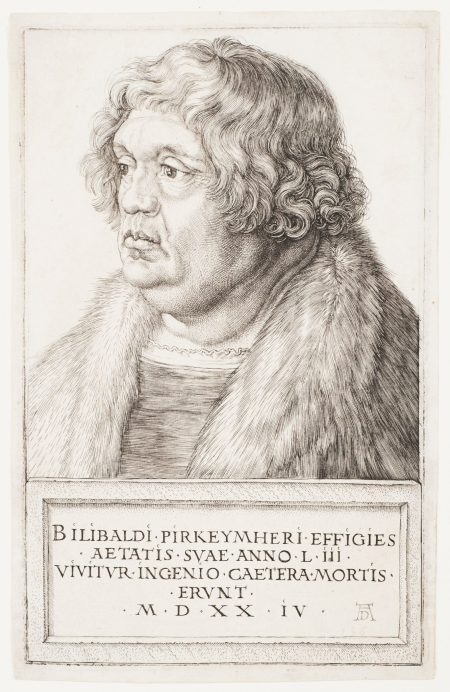

Germany

Willibald Pirckheimer

1524

engraving

Bequest of Edmund Kemper

1960.909

If we are looking for what is most Reformation-like in Durer’s artistic career, the exhibition has a wall where a number of engraved portraits have been gathered together. They are in many ways in the style of the unadorned humanist portraits. (One of the best of Durer’s humanist engravings is technically not that of a humanist at all, but his “St. Jerome in his Study” [1514], which shows the Bible translator at work at his desk in a private, well-lit, 16th century space with books and paper in evidence.) As a group, they consist of such figures as the humanist Erasmus (a great fan of Durer), the Reformation resister Cardinal Albrecht, and Reformation theologian Philip Melanchthon, who has the faraway look of a saint in modern dress. One of the most powerful of these portraits is of lawyer and author (he translated a book about hieroglyphics) Willibald Pirckheimer (1524), Durer’s friend and patron. Pirckheimer helped to suggest, as humanists often did, the program for complex civic visual allegories, such as the monumental triumphal arch for Emperor Maximilian which was made up from nearly 200 individual wood blocks, dense with symbolic indicators. Durer’s own master prints, such as his famous “Melancholia I” or the engraving we know as “The Knight, Death, and the Devil,” are cluttered with allegorical elements that link the artist’s intellect and aesthetic both to the Middle Ages and to the Humanist appetite for fragmented symbolic systems where the parts are in danger of overwhelming the whole. Though not really a scholar himself, Durer was drawn to the scholar’s instincts. In formulating his own book on human proportions, Durer reported that it was very helpful to have met Venetian artist Jacopo de’ Barbari, but was disappointed that his understanding of the body was not sufficiently systematic, and reported that he had go back to the ancient Roman Vitrivius to get what he needed. Humanist portraiture is a warts-and-all art form and Pirckheimer was no beauty, but Durer has captured his fur, wavy hair, and rolls of flesh in such a way as to suggest a rich inner life: he was the middle class man who valued the life of the mind. Like his other late portraits, Pirckheimer is a private man who has had to step forward into the public world.

The CAM’s exhibition accounts particularly well for the economics of the world of print in which Durer was engaged for practically his entire career. Towards the end of his career, he briefly earned a pretty good pension from Emperor Maximilian, but chose to continue to make new prints and sell copies of his older ones, because you can never tell. For Durer, the world of prints was largely the world of books. As an artist, he served his apprenticeship in the shop of Michael Wolgemuth, who contributed illustrations to the Nuremberg Chronicle, a massive compilation of what was known about the world in 1493, with hundreds of separate woodcut illustrations, some of which were probably designed by Durer and some of which might even have been carved by him as well. The show has a blind spot in its omission of The Ship of Fools, a late Medieval-early Humanist potboiler satire about dozens of different forms of folly and stupidity, for which Durer is reputed to have designed a portion of the illustrations. Many of what we think of as Durer’s best-known woodcuts are actually individual pages from books that he published, such as his “Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse” (1498) or the nudes he used to illustrate his ideas on human proportion (1525).

One of his late-career books on perspective is open to a page where two men labor like industrious craftsman with a paned window-like perspective device that lets them capture the lute from any angle. Not shown at the CAM show is another woodcut where the artist stares through a similar perspective frame at a reclining, mostly nude woman, her feet facing the artist, while he studiously draws her. His intense examination of her, ripe with sexual implications, is a strange and often commented upon mixture of intimacy and clinical distance. Perspective is a technique that both confirms the immediacy and privilege of point of view, but also allows you to hold onto your separation from the thing being seen. One would like to know what vision of the artist as a seeing creature the book on perspective ends up with. Durer’s commitment to the book as a medium is all the more startling when we appreciate how new an invention the moveable type book was in Durer’s world—an information-sharing technology that went from its infancy to Durer’s Apocalypse in less than a half century. It is also interesting that the most desirable versions of some of these series—and therefore the ones more likely to have been in Herbert Greer French’s collection, as he had an eye for what he thought was the finest and rarest specimens—are woodcut proofs before the letterpress of the book was added, allowing us perhaps to see more detail, but effacing the intended context for Durer’s art.

Durer himself was never abashed to be associated with books. His mid-career masterpieces include woodcut series of The Life of the Virgin and The Passion of Christ, as well as an engraved version of the latter. His style fell comfortably, if industriously and often with great inspiration, under the general heading of book illustration. He learned from woodcut design how to tell stories within strict limitations. His central graphic works were woodcuts executed in black and white, carved on blocks of fruitwood almost certainly by other craftsmen and printed on handmade paper by still others. All the lines are more or less the same thickness, so if your composition tends towards the crowded, it’s easy to end up with a print that, from even a short distance, loses its highlights in a dense grey. And crowded they were. Between his Humanist desire to retain the central symbolic details of each piece of the total story, and his Renaissance inclinations to honor the individual by not generalizing the faces of the bit players in his prints, even of a mob, there is a lot competing for our attention. Like other artists of the Danube School (who helped bring the modern landscape into being), he also cannot resist filling up the spaces with weeds below and birds above, each of which may have links to sacred allegory but which, in Durer’s hands, sometimes seem like, well, weeds and birds.

Germany

Joachim’s Offering Rejected for Life of the Virgin

circa 1504-05

woodcut (proof before text)

Bequest of Herbert Greer French

1943.216

One of Durer’s central achievements is that he could make a monochromatic picture so detailed and still keep it readable. In one of the blocks from The Life of the Virgin, “Joachim’s Offering Rejected for Life of the Virgin” (1504-05), based on a lesser-known moment in the New Testament when Mary’s father has the lamb he has brought to the temple thrust back at him, we get the chance to see Durer’s story-telling and pictorial techniques. As with all his mature woodcuts, the lines are loose and natural, and capturing of the cross-hatching is remarkable; I found myself wishing I knew more about the skilled craftsmen who cut the wood, the tools they used, and the training, deference, and pay they received. In a print that is smaller than 8 x 12, there are no fewer than 20 figures, from children to senior citizens, with hats, costumes and, of course, draperies. The crowd is very socially varied, seeming to range from thugs to courtiers. Some are talking in small groups, one is putting on his glasses so he can read from a book, and others are carrying their sacrificial lambs with them. Some are watching the unfolding drama, some are averting their gaze, and others seem wholly unaware. As viewers, we are at a safe and respectful distance. The figure closest to us is a child with his back turned towards us. Are we looking with his eyes? The drama unfolds before us as if it were being performed on a stage and we are secure in some gallery; this too is an exercise in perspective. And all this is just in bottom half of the register. Behind them, there is a curtain, perhaps because some elements of this story will always be a mystery. Behind and above the curtain, we see the plaster of the walls starting to peel off to reveal the brickwork beneath, which feels like a miniature sketch of how human history works, where there is an ongoing drama between the old and the new.

It is hard not to be startled to move from the woodcuts to the etchings and engravings, where we have the chance to see the unmediated handiwork of the artist directly on the plate. For an audience used to the remarkable lines of woodcuts which still cannot help but be formal and just a little stiff, buying an engraving must have felt like owning an actual drawing by the master. The engraved line is autograph. It would be interesting to know about comparative prices and even marketing. You have a genuine sense of being in the presence of the artist as he draws, and perhaps even as he prints: in one of the plates of the engraved version of the Passion (1507-12), there is a ghost of thumbprint that might well be Durer’s, we are told. For all of the immediacy and technological progress represented by the engravings, Durer often kept to the compositional models he had worked out in the woodcuts. You can get a feel for this by comparing his woodcuts for The Passion of Christ with the engraved versions of the same scenes. Why give up what you’ve learned about how to tell a story?

Durer made prints of unsurpassed gravitas, but he did not hold back from those staples of western art, sex, violence, and otherness. It would be very interesting to know something about the sales of some of these works. His woodcut of the “Rhinoceros” (1515) went through eight early modern editions, a tribute surely to both the animal’s otherness and its monstrosity. The martyrdom of saints will increase an artist’s gore quotient and body count in a hurry, and the roots of such scenes—of both horror and celebration–go back almost as far as Christendom. Nonetheless, it is interesting to try to imagine the purpose of his 1497 woodcut, “The Maryrtyrdom of the Ten Thousand.” There are many Christs suffering for their faith here, many cruelly indifferent Pilates, and many sets of tyrannical Roman soldiers. One possible clue to the purpose of such a print is in the oil version he painted a decade later. In that painting, which is generally very similar to the earlier woodcut, he placed himself as a calm observer, bearing a flag with his name, in the geographic center of it all, looking on. “The Sea Monster” (1498-1500) is an interestingly puzzling engraving. A nude woman (as many descriptions of it point out, she is not young) is being carried off by a human-faced merman, of sorts. In the distance, other humans down by the water’s edge are frantic or grieving. Not so the woman. While clearly not happy, she is at least resigned to her fate and, as many have pointed out, more interested in posing in her elegant nudity than she is in resisting her abduction. The literature about the print is crammed with mythic interpretations or historical analogues, but there is something more basic to the pose, more folkloric, more archetypal. Unlike the figures on the shore, she seems to understand her fate. The monster is equally dispassionate. It has the appearance of the fulfilling of an old contract. It is almost as if it is a picture of some justice being fulfilled, carrying her away to a destiny that is unclear, but is surely sexual in nature.

There is an odd and interesting arc about gender issues in the Museum’s show which, while not explicitly foregrounded, is hard to miss. There is something either mysterious or blank about Durer’s women. While not exactly looking like Michelangelo’s women, who, as many critics suggest, may have been modeled from men with breasts (or “breasts”) added on and penises removed, they are frequently hefty and well-muscled when nude and clotheshorses otherwise. With an artistic style that relentlessly humanized the crowd, regardless of how dangerous or low-life they were, his women are typically idealized beyond being characters. (This is even—or perhaps especially—true of the Virgin Mary in the woodcut series about her life.)

And then there’s the sex. In the engraving that has come to be known as “Coat of Arms with a Skull” (1503), a figure of the folkloric wild man is getting somewhere with a young patrician woman, possibly a bride. She is more flirtatious than bashful, and has her fingers entwined around the buckle of a leather strap that is holding up a helmet with an extravagant arrangement of feathers. There is something deeply fictive about it all—the helmet only makes sense as a three–dimensional representation of a two-dimensional design engraved on some other metal surface than an engraving plate. But the skull is deeply sinister, of course, and suggests the end result of this dalliance. Like the sea monster, the wild man is more seductive and reflective than he is passionate. The overall impression is tied to the Dance of Death, one of the Middle Ages’ great equalizing images, though it’s complicated by their clear distinction in social status or even sexual desire.

Promenade, circa 1497, engraving, Bequest of Herbert Greer French, 1943.181

Even more strongly connected to the Dance of Death tradition is “Promenade” (1497) in which a pair of young, well-to-do lovers are out for a walk in the country, their hands entwined. Behind a tree, Death lurks, holding an hourglass on his head. It is not hard to “get” the point of the print; audiences had been “getting” such images for centuries by the time Durer came to make this engraving. On the off chance that we are not focusing on what is essential, the young man wears his sword on a belt around his waist straight in front of him, the upright grip right in front of his crotch. Still, the figures are sympathetically rendered, rather than, say, appearing merely heedless—or at least the male figure is. But the Dance of Death makes most sense in a series like, for example, the one Holbein would do around the second decade of the 16th century. The king, the knight, the bishop, the mother, the couple in love, even the humanist looking up at his model of the universe: death comes for all. But in Durer’s oeuvre, there is hardly anything more dangerous than to be part of the male-female couple. The lurking danger of heterosexuality is killing them.

Somewhere in all this, we have to make a little room for “The Men’s Bath” a woodcut from around 1496-97, one of several of his prints that feature groups of men who are currently doing nothing very much. Four mostly nude men are relaxing in the bath while two others, equally unclothed, are playing music for them. One of the men is drinking; one holds a scraper and another holds a carnation. These last two are gazing at each other very intensely. A fourth man leans against a block of wood out of which comes a faucet at what is surely intended to be a very suggestive spot right in front of his crotch. Audiences had been “getting” images like these for centuries too; just look at the walls of Pompeii. The man leaning near the faucet has an expression that isn’t readily readable. Perhaps he is amused by it all; perhaps he is delighted; perhaps his look is one of yearning as he stares at the drinking man. Some scholars believe the drinking man is Pirckheimer; many tend to identify (with more absolute assurance than I feel) the gazing man as Durer himself—and it is certainly fair to remember that Durer inserted his presence into a number of his other images. If indeed it is supposed to be a self-portrait, this Durer has his hair up in a topknot and is particularly ripped.

Some scholars suggest that the four men represent the four temperaments, and others propose that they are the four senses, but I’m not buying either of those. It seems an image that celebrates an intense homoerotic attraction between several of these men. Yet it is a perfectly chaste image; no one is touching anyone else, and there are no skeletons lurking in the background. They are frozen by what they are seeing. A fully-dressed figure is standing against the rear wall of the bath looking on, perhaps attracted in some way to what he sees. Does he want in or out? For him, the men and the musicians might be a miracle, an aberration, or a sideshow, or they might even be a mirage, a transitory image that might disappear if he moved either closer or further away.

The world of Durer’s graphic art is a world of spectacle. It is a world that adores the act of seeing. His Reformation sympathies, whatever they were, to the contrary notwithstanding, Durer tends to place his audience in the position his St. Gregory found himself in. Something amazing is unfolding before our very eyes, and we have the chance to take it in. Although the prints made ownership of art within the reach of far more people than could consume objects of visual delight and intensity in previous centuries, there is still the lurking sense that it is a private moment, a private show. Those who ignore it are like the rest of the townspeople in the “The Men’s Bath”: in the distance, a man is going fishing and up the path a ways, a woman is drawing water from the well. In looking at the man outside the fence, his back to the town, looking in at the male bathers, we are looking at a version of ourselves.