A Dayton, Ohio living room has been converted into a simulation death chamber. Walk through the door and it hits you in the stomach: the smell of disinfectant and an uneasy superposition of the state and domicile. There is a gurney primed for lethal injection. You can see it through plexiglass picture windows in a newly constructed wall, enclosing a third of the gallery. There is no way in or out of this room. Lit from beneath, the black gurney casts a rippled shadow on a curtain of institutional green. The shadow resembles the form of a body, arms outstretched. From safely in the living room converted into a gallery, you might imagine yourself reclining on the black vinyl cushion, straps wound tightly around your torso and appendages. Supine, ribcage confined, arms extended, you might imagine your wrists swabbed with cool disinfectant, then a needle puncturing a vein in each arm. The cocktail administered is the ultimate expression of state power, delivered intravenously in succession: midazolam to relax and sedate; pancuronium bromide to slow breathing and confine mobility; potassium chloride to arrest the beating of your heart. You might imagine yourself relaxed, breathing slow and shallow, and in your final moment you direct your gaze to the wall and notice its interior constructed from plywood. A stage prop for your death.

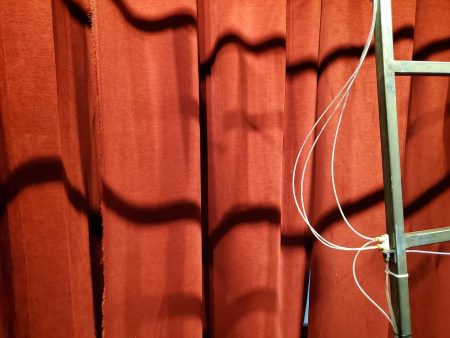

On the opposite end of the gallery, positioned before a red curtain and illuminated by lights, cold steel and plastic tubing form a large cross. This is not a pleasant devotional icon but a holy terror of automatic death. Whereas the lethal injection chamber was sealed, this is an open stage. You approach the machine and feel the heat of the lights. There is a joystick mounted on a protruding arm. There are printed instructions: “Push to engage. Pull to retract.” You push the joystick. The machine sighs to life. Compressed air exhales through pneumatic piping. A crown of long metal spikes encloses around where a head would be positioned. Nails push inward at the points of wrists and ankles. Automatic stigmata. There is a clicking of metal on metal, and the horrible machine rests. It occurs to you that, had there been a body present, you would have set in motion the wheels of execution. Looking up at the horrible machine, it also occurs to you that its mechanisms, though excruciating, are not directly fatal. They are systems of penetration and confinement. Eventually the sentenced individual would run out of oxygen and, like the machine, fall silent.

Artist Michael Casselli has called this exhibition at Blue House Gallery a tacit agreement. Standing between these two works is a visceral experience, and it’s only after letting one’s gut settle that the artist’s chosen language begins to take hold. Certainly, this is an opportunity to meditate on the stark actuality of capital punishment and the relationship between the state and the body. Additionally, in this setting — a gallery within the walls of a home — that relationship can be extended to a question of public and private (or state and domicile). This latter point is emphasized by the presence of curtains and stage lighting. In terms of the experience of the work, these inject an element of Lynchian surrealism. Discussing David Lynch’s use of curtains in his film and television oeuvre, Mark Fisher writes: “Curtains both conceal and reveal. […] They do not only mark a threshold; they constitute one: an egress to the outside.”[1] The space between these curtains — one blood red and the other institutional green — establishes the gallery space between as oneiric. It becomes an uncanny valley between state power and individual agency. The presence of two stages — one open, the other closed — doubles this as a tension between subject and object.

The eeriness of these works is also palpable in their sterility. They are each bodily, yet bodies are absent. Above the lethal injection gurney, we see a ghostly shadow with outstretched arms. In the case of the mechanical cross, it is clearly itself a body: It breathes. It has appendages and a circulatory system. The instructions printed on its arm compels me to move its joystick, activating its machinery. What has compelled me to move its joystick? A sense of curiosity? Social pressure? At the point of action interface, the machine is a prosthetic of my own body — and my own actions are the prosthetic of a larger outside system, of which I don’t have a clear sense beyond its outsideness. Whatever it is, it encompasses the mechanical cross and the implicit contract of interfacing with a work of art in a gallery.

An interpenetration of subject and object has taken place on this stage-within-a-stage, and it is metonymic for the behavioral mechanisms that transpire as state power moving through the social body.

Beyond the walls of this gallery, a virus moves through the population. At writing, there are half a million infected. As the body count climbs, the lives of individuals have been pitted against the health of the stock market, an emergent prosthetic body itself. If, in the coming weeks and months geronticide is effectively enacted by the state, to what tacit agreements did we consent?

–Steve Kemple

[1] Mark Fisher, “Curtains and Holes: David Lynch” in The Weird and the Eerie. (Repeater Books: 2016), pg. 53