In light of the recent death of Muhammed Ali, I wanted to revisit his biographical career via Michael Mann’s 2001 film Ali. My curiosity to revisit the film peaked while watching his lengthy funeral service two weeks ago. Specifically, I wondered if the film held up 15 years later, and the short answer is no, and it never did.

The world’s outpouring for the death of Ali was an interesting event to witness. Fans, admirers, and removed onlookers received his life’s memoir via every media outlet available within the span of a week. His tributes showcased his athleticism, political activism and religious devotion while providing an even, if not at times grandiose summation of his life.

But just as the significance of his memorial service was lost (as the tragedy in Orlando took place 24 hours after) the film based on his life and career is an overdrawn, somber account not worthy of the man so glorified by the people and perhaps most importantly –by himself, if he were still with us.

In screenwriting, “show… don’t tell” is a cardinal law. If you can’t show it to an audience it has no business existing. This film manages to show, yet has nothing to say. Bio-pics since 2001 have become somewhat formulaic; and rightfully so, as they are difficult to execute successfully. Flashbacks, conflicting points of view and character arcs are all too ubiquitous, leaving only a handful of films standing out since 2001 (Walk the Line, The Social Network, Hotel Rwanda, Moneyball).

Yet Ali is one that is never mentioned.

It encompasses a critical 10 years of his life. Starting in 1964, when he won the world heavyweight championship as Cassius Clay, to 1974, when as Muhammad Ali, he fought George Foreman in the Zaire Rumble, the film’s flat conclusion. The screenplay by Eric Roth and Mann seems timid to find its footing on a specific direction of what “type” of Ali they want to portray: the family man, the business man, the public’s hero. It wouldn’t be a problem to have all them exist – yet the audience has to know early on who they are dealing with. Character trust is never established. The result is a polarizing figure to identify with, leaving the notion of understanding why he’s a prominent figure but not appreciating it.

The great value about Michael Mann is that he is a talented perfectionist, yet this material is wrong for him (he should have passed, as this film went through many hands and false starts before his involvement). 1995’s Heat, one of the best action movies ever produced, benefits from his understanding of a paced crescendo of energy, finalizing in an airport shootout that is as much about character development as its action. This material for him is just too dense to fit into a laborious 3 hours. His pre-production on the project was a solid two years of research, choreography and overseeing Will Smith’s impressive transformation into Ali. Not one piece of clothing is ill hemmed and not one punch is thrown inaccurately, but this precision carries a noticeable importance rather then setting a consistent narrative tone. This is not a straight-laced telling, nor would it benefit to be one – however, the editing is rushed leaving scenes no room for breath and experimentation for actors to inhabit. Besides Smith’s portrayal, several historical figures are used, yet sidelined, by the iMovie editing type organization. The cast includes Jamie Foxx (Drew Brown), Jon Voight (Howard Cosell), Mario Van Peebles (Malcolm X), Ron Silver (Angelo Dundee), Jeffrey Wright (Howard Bingham), Mykelti Williamson (Don King).

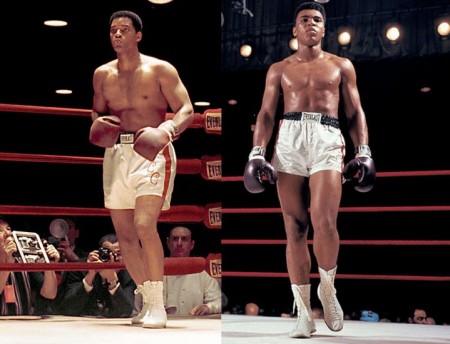

Even with its evident production problems, the real reason people watch is for Smith. Smith’s career was at a high point back in 2001 and has since stumbled as his movie star status has changed to niche projects, yet he has been consistent as of late. After coming off successful blockbusters (Men in Black, Independence Day, etc.) this was a clear passion project and will probably be his most realized career role. Adding 35 pounds of bulk and muscle to his frame, and adopting not only the symphony of Ali’s essence but his vulnerability, Smith plays each scene to its apex, whether it’s contemplative or the familiar brashness the public knew Ali by. He works best against other actors up to the challenge, not an easy feat yet Jon Voight’s Howard Cosell and Jamie Foxx’s Drew Brown play like great jazz opposite Smith and provide realism the audience feels secretly invited to witness.

The film provides more snippets than source when dealing with Ali’s life not central to boxing. His known womanizing, the assassination of Malcolm X, his refusal to step forward during Army induction and the stripping of his title for evading service during Vietnam are presented in cliff notes fashion. His career was mired in controversy, which the story does not shy from, though it has been mythologized over time – positively or negatively depending on your admiration for the man.

15 years after its Christmas release in 2001, Ali, the man, has not only grown in myth but in cultural, athletic and spiritual form. His funeral service was a celebration of individuality and call of reform for world peace. It was a spectacle only he could orchestrate, which he did – as he planned his own service for the last 10 years of his life. In its purest form it was thought provoking to witness, making Ali all the more of a missed opportunity to measure in stature.

2/4

Steven Havira

Artist, Actor, Writer/Producer