Lebanese artist Nabil El Jaouhari has only been in Cincinnati a short time, but since his arrival six months ago, he’s created a body of work that continues his visual investigation into the power of memory. Through a variety of media and approaches, he reconsiders the fixed impressions from a childhood marked by conflict. Born in 1976, he grew up in Aramoun, a village about twenty miles south of Beirut, the place where he witnessed his country engulfed in civil war.

When I visited his Clifton studio to discuss his work, El Jaouhari explained his uncanny ability, developed at the tender age of five, to identify a bomb’s direction. From the safest place in his home, a hallway where the family slept for almost two years, he could identify the sound of missiles, knowing whether one was coming or going. It’s evident just how engrained this memory is for him, since he casually offered it up while musing about his love of the color pink.

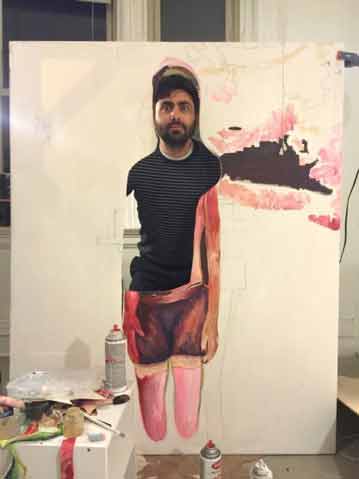

Before coming to the United States for graduate school, El Jaouhari attended art school in Lebanon, where the broad curriculum followed what he describes as a traditional French model. The rigorous training included stained glass, mosaic, printmaking, weaving, ceramics, sculpture, and painting. In his current practice he tends to turn to mixed media he identifies as personal: wallpaper, glitter, stamps, olive oil, torn pieces of old drawings and paintings. Dismantling older work to reinvent the remnants into new visual configurations is an integral part of his practice, and he has recently introduced a wood-burning tool into the mix. It’s easy to understand how closely intertwined he is with the heaps of material scattered around the floor of his studio; the disarray tends to reflect just how much of his work is about the process itself. When I ask about a bundle of woven white fabric I notice piled on a shelf, he pauses. The fabric is his creation. He spent six months weaving 24 yards of cotton as a way to connect to his late father, a professional rattan furniture maker. It’s always the memory, he explains, “Memory never leaves. For me, it finds itself through this repetitive form.”

Though it’s undeniable the atrocities of war will leave a permanent imprint on the human psyche, El Jaouhari acknowledges his own recollections of war as something akin to a stain. It’s this very stain that commands his careful attention, allowing him to transform memories into a visual lexicon, an abundant source for a striking array of imagery that effortlessly blends vibrant color palettes with both figurative and abstract forms.

You speak openly about the war in Lebanon during your childhood. The reality of that is difficult to grasp for most of us here in the States. What memories of war continue to find ways into your work?

Syrians and Palestinians, Israel, all took part in the Lebanese Civil War, much the way that today Syria is a battleground for Russia, the US, and Iran. It was the war of others, but on our land. There was also the religious segregation and other fucked up shit happening. I have fragmented memories—visual images—still very raw in my mind. One is of patterns, patterns I noticed on different soldiers. Another memory involves a young, hopeless-looking Syrian soldier getting a haircut in a partially destroyed building. I’ve been literally trying to recreate the image of this idea of the guy having his hair cut. I see how my own history is embedded in this image, so I’m trying to make it my own.

Does this process of tapping into the past in order to extract a visual impression lead you into uncomfortable territory… as in perhaps finding you’re depicting particularly traumatic events?

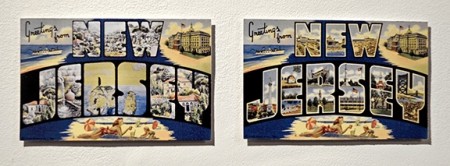

I had a previous exhibition about the USS New Jersey, a battleship that, in the 1980s, fired huge missiles into Lebanon. They were so huge, so heavy, that they were referred to as VWs, because they weighed as much as a Volkswagen car. All of these VWs missed their targets so they ended up killing nothing but civilians. One of them landed in my village in the middle of the street, but luckily it never even detonated. I remember walking around that thing for like four, five, maybe six months, just to get to school. That entire time that thing is in the middle of the street, as big as a car, literally in the ground. I remember kids jumping on it—it was just gigantic! And the funniest part of it is, here I am, after like thirty years or something, and I was in a vintage clothing store in Missouri, and I see this postcard for the state of New Jersey, saying “Greetings from New Jersey.” Inside each of the letters was a scene of a New Jersey landscape. I don’t know if it was traumatic, but this image had a very different meaning to me and I used that card and inserted Lebanese watercolor landscapes, a kind of genre that’s considered a lower form of painting. In an exhibition of my work in Columbia (Missouri), I displayed this image alongside the original card. Next to it I had a wall display consisting of 300 tiny VW cars I created; they were arranged into the shape of a bomb. I just wanted to tell a history of this battleship by changing the caption. I wanted to rearrange it, reestablish it visually.

You came to the U.S. to attend the MFA program at the University of Missouri. What was that like, coming from Lebanon to Columbia, Missouri?

I sometimes felt a sense of displacement in Lebanon, though I was always open about my sexuality to my friends. I think when I came to the States I expected to experience more diversity in my graduate program and I don’t really think I found that. Some of my professors didn’t understand why I was trying to make work about my experiences, especially when it involved my sexuality. I was trying to do many things at the same time. I wanted to explore so many possibilities. In general, I was trying to understand my entire history as a homosexual, but I never really stepped away from it and looked at it until I was in that place. It’s layered. It’s not one thing. Being gay in the US, I sometimes find people try to put me in a certain category. I also find people tend to assume that, because you’re Arab, you’re Muslim. I often have to explain how Lebanon is not a Muslim country. I have to explain that being Arab is a race, not a religion. People who know me, I think there is something about me that makes them forget I’m a foreigner.

You’re also Druze, and since I’m sure most people don’t know about this ethno-religious sect, can you provide a basic explanation?

Druze is monotheistic, and it’s also a minority religion. It combines Far Eastern religion with the three main faiths from the Middle East. The Druze are supposed to only marry other Druze. You can’t marry more than one person at the same time, but you can remarry. It’s also very interesting that such a minority religion can exist with so much power. Druze controlled land and money, so they always held that kind of power. The first municipality in the mountains of Mount Lebanon, it was for the Druze, given by the Ottoman Empire. Druze are also in Israel, and now a major part of the Israeli Army. In Syria Druze is big, even though we’re a minority. But also the Druze played a very crucial part in the modern history of Lebanon. In the Civil War they were one of the major players.

How has being Druze shaped you as an artist? What role did art play in your childhood?

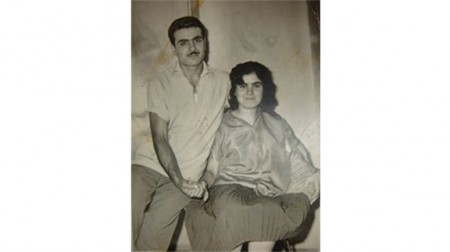

There is that kind of special feel of being Druze, a pride about it. I was never really involved in anything that was specifically Druze, but I kind of miss that small town feel of it here in the U.S. It’s hard to find a Druze person, though in Texas there’s a Druze community. I don’t know that being Druze specifically influenced me creatively, but it was definitely my dad who was my biggest influence. He used to give me money to buy something I would need, like a pair of shoes, but at the same time he’d give me money to buy paints because I was always the kid off in the corner, just sitting and drawing, doodling. Understanding that about me, that came from a guy who never went to school. My father was uneducated because his dad died before he was born. His mother took him to the city to work as a laborer at a very young age, selling trays of water at the age of five years old. When he was eight, he became an apprentice in the workshop of a furniture maker. He still taught himself to read and write. He made himself from nothing. He made beautiful furniture in his shop. He would take a stick of bamboo and heat it on the plate and then curve it on his knee to create a chair. He also used to stretch canvases for me. He was proud of me, even in his limited understanding of contemporary art. My dad was an amazing person.

You have mentioned that artist Mona Hatoum and author Rabih Alameddine both influenced your creative development. Aside from their connection to Lebanon, what about their work resonated with you? Who are other artists you admire?

With Hatoum, there’s that balance between her storytelling and her high quality of art making. She has intense issues to talk about and knows how to find that beautiful bridge.

Rabih Alameddine just fascinates me. In I the Divine, he tells a tragic story, like Greek tragedy kind of stories. He writes only in English but there is such a connection. And my brain no longer knows English from Arabic or other languages anymore… they’re all sort of mashed up in there! But my work is self referential, like biography, so I do feel a personal connection to these artists for that reason. I like so many other artists, it’s difficult to list, but some of my favorites are Dana Schutz, Neo Rauch, Peter Doig, Gerhard Richter, Ann Hamilton and Mark Bradford. And I’ve always loved the paintings of Chaime Soutine. I was also influenced by Mohammad El Rawas, my former printmaking professor from undergraduate school in Beirut. Oh, and there’s Fatima El Hajj. I really like all the contemporary art happening in Beirut right now. Ashkal Alwan, the Lebanese non-profit art organization, has this event called Home Works that happens every year. Beirut is an incredible city for art; it’s very supportive of the arts.

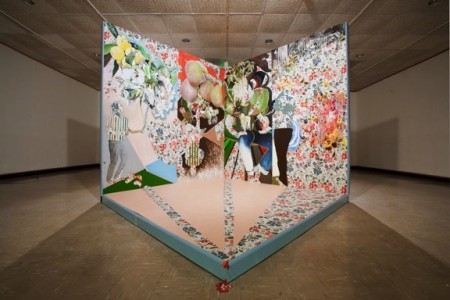

What do you want the viewer to take away from your exhibition? Is there something in particular you hope to communicate most through this body of work?

Though I’m intrigued to see how the pieces are forced to sit together in a synchronized way, I want the viewer to find the nonlinear narratives, the different ways to tell a story, through the points they can connect. The memory of some of the pieces can then find a way into another story. When you look at something that’s not one thing or the other, you kind of make it one thing or another by your own perceptions. I like the idea of this exploration of memory.

Memory Pacifier is the title of El Jaouhari’s solo exhibition at the University of Cincinnati Clermont College Gallery, where he’s the visiting artist for UC’s annual International Education Week. The exhibition runs from November 1 through December 14, 2016.

–Kim Rae Taylor