The impression that stays with you after viewing Kurt Grannan’s show at Wash Park Art is of figures with white faces, holding poses and commanding you to pay attention to the meaning of their performed identities. This exhibit of thirteen mostly figurative oil paintings demonstrates versatility in subject matter and technique. An Assistant Professor of Art at Mount St. Joseph University, Grannan has written that art should address social issues. This social mission of art is seen in the vulnerability of the people in his paintings, in the way they use masks to survive in a world that would exploit or categorize them.

Art with a social mission can be problematic. If the message overwhelms the art, it runs the risk of becoming commentary at best and propaganda at worst. Grannan avoids this danger by his skill as a painter and the respect he feels for his subjects. The women in his paintings, some wearing only bras and panties, are exposed, their bare arms and shoulders thin and pale. They are seen in stark urban settings. Yet, in the way Grannan depicts their bodies, particularly their arms and hands, these women have an inherent dignity and an aristocratic grace. Their faces, mask-like or literally turned into masks, are jaded, leery of how the world views them, but suffused with strength.

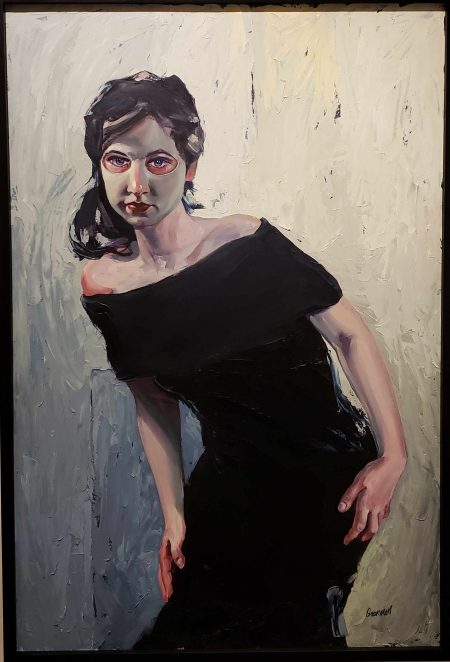

“Verna,” the most striking painting in the show, is an almost full-figure portrait of a woman in a formal, dark dress. Hands on her hips, she leans forward and bends at the waist, as though she is trying to fit into the frame of the painting. The composition is astonishing. The curve of the woman’s body makes her appear off-balance, but her face is perfectly level and looks straight at the viewer. Dark hair, falling to one shoulder, frames the face. Her hands clasp her body, helping her hold her awkward pose. The black dress sets off the pale skin of her hands, arms and shoulders. Her face, except for the area surrounding her eyes, is almost white. On inspection, it becomes clear the face is a mask; only the blue eyes and the skin around them are uncovered. Has the woman been manipulated into this sexualized pose? If so, her masked face and penetrating eyes indicate there is a part of her that cannot be dominated. The elongated torso, pale skin, and dark dress of “Verna” echo another eroticized depiction of a woman, Sargent’s “Portrait of Madame X.” Whereas Sargent’s subject acquiesces to the male gaze, Grannan’s defies it.

Grannan is even more explicit about the sexual exploitation of women in two paintings set in what appears to be a dressing room where women prepare for some kind of performance. In the larger painting, “Smoking in the Changing Room,” the setting is sinister, a noir mixture of smoke, dangling electrical wires, and off-balance walls and doorways. The message about smoking is almost too obvious in the multiple cigarettes dangling from one woman’s mouth.

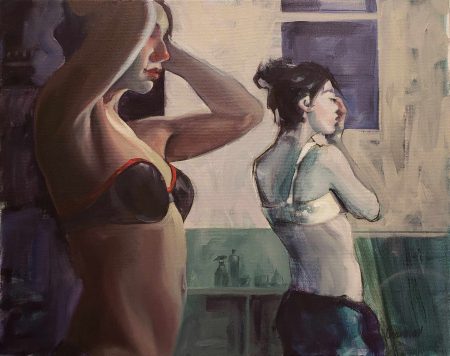

“The Changing Room” a smaller painting, shows two women in bras and panties preparing their hair and make-up. The woman in the foreground has her arms raised to her hair. This pose allows Grannan to paint a beautiful rendering of the woman’s bare arm and upper torso. Her face is framed by her arms, her eyes all but hidden, her full red lips the dominant feature. The almost naked woman has a look of resolute dignity. The second woman is seen in a harsher light that makes her skin appear pale. One hand is raised to her face, seen in profile. She is intent at applying her makeup. The bras so prominent in this painting, rather than being delicate or titillating, suggest in one case a breastplate and in the other a bandage, clothing these women wear for protection as they prepare to perform. In its composition of vertical and horizontal lines and its carefully modulated color palette, “The Changing Room” is a beautiful if troubling painting.

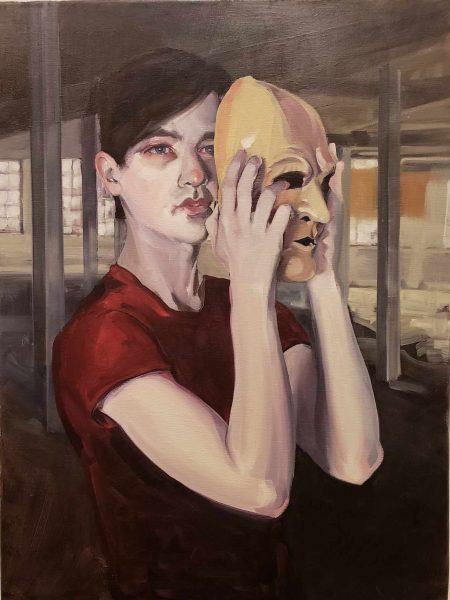

Most of Grannan’s subjects are women struggling to maintain themselves under difficult circumstances. “Cole” is a subtly executed portrait of a young man. The painting demonstrates Grannan’s incorporation of hands and arms in his portraits and his use of masks to suggest the interplay between identity and conformity to societal expectations. With both hands raised in front of his face, the young man holds a mask of a stylized mature male face. His skin is paler than the flesh tone of the mask. This young man appears to be removing his own identity or perhaps considering an alternative identity. Cole has the sensuous red lips found in all of Grannan’s portraits. This, along with his slender body and delicate features suggests gender fluidity. Behind Cole is a large room with a number of vertical columns threatening, like prison bars, to confine the young man. Cole looks directly at the viewer, as though appealing for understanding. The wonder of the painting is its ambiguity, of the myriad interpretations it allows.

In most of his portraits, Grannan paints the background with simple, basic strokes: a wall, a window, an open space. As a result, it is surprising to see him also offer paintings filled with minute details. “This Food Is for the Birds” is a brilliantly colorful and skewed view of a restaurant that pivots from the corner of a table set with dishes of food to encompass the whole room.

“Waitress” starts with a similarly off-kilter view of the sink behind a lunch counter. Grannan masterfully captures the shiny metal surfaces of the sink and the translucent glassware set to one side. The right half of the painting is given to the figure of a woman holding a large white dishtowel. She is seen in profile with her hair pulled away from her face. With her elongated torso and the graceful curve of her stance, this waitress resembles a goddess, a woman superior to her surroundings, something lost on the two shadowy men sitting on the other side of the counter. The painting is a tour de force of perspective, detail and coloration.

“New Nadia,” a vividly colored portrait of a young woman, further demonstrates Grannan’s versatility. Present are his characteristic mask-like face with pale skin and red lips. But this is a happy painting. A simple red hat crowns the young woman’s head. Her dark hair flows to her shoulders and becomes, at an indistinguishable point, a hijab. The young woman’s eyes are blue and blue shadows surround them. The background is bright orange, echoing the gold background of Christian icons. There is a tranquil expression on the young woman’s face, as though she has discovered something that pleases her and wishes to share it with us. This sense of communicating an important message is further accentuated by Nadia’s raised hand, her index finger pointing upward. With its flat surface, vivid primary colors, and stylized gestures, “New Nadia” resembles early religious art, an icon that blends both Christian and Muslim imagery. Unlike Grannan’s exposed, vulnerable women, Nadia is not performing an identity. The woman in this portrait is in touch with her true self. As such, she is a challenge to our intolerant times.

“Out of the Dark” is a small show filled with artistic vitality. It is perfectly suited to the Wash Park Art Gallery space. Viewing it, we cannot help but respect his concern with social issues. Nor can we resist admiring his considerable skill as a painter.

“Out of the Dark” runs through May 26 at Wash Park Art.

–Daniel A. Burr