In the artist’s statement accompanying Matthew Metzger’s showing of ten new paintings at Miller Gallery, Metzger articulately lays out some of his goals: “In an overwhelming landscape, harsh, indifferent, opposite to arguably our most endearing human traits, we recognize our humanness.” In a nutshell, Metzger is here describing our relationship to the sublime, an aesthetic category that has been with us since the 18th century (which rediscovered it from the classics) and truly came into its own with Romanticism. We can find our true selves in a landscape that affords us no comfort, and possibly even no place. Nature, as experienced in the sublime mode, is a world out of proportion to human measure. It is traditionally distinguished from beauty. (A garden arouses our sense of the beautiful; the Grand Canyon arouses our sense of the sublime.) The sublime appeals to the part of us that is drawn to storms and mountains. It is a vision of nature on the verge of formlessness, and is likely to inspire in us awe and perhaps even terror. In return, the sublime unbinds our spirit from its material reality and allows it to expand, potentially without limit.

To engage with the sublime is to find oneself attracted to the otherness of nature; as Metzger puts it, this is the nature that is “opposite to arguably our most endearing human traits.” A painting that engages with the sublime sets itself off from the tradition, say, of the Hudson River landscapes of the 19th century, which pictures rugged scenes where human beings are still connected to the natural world around them. Somewhere out there in all those forested foothills of the Catskills, we can catch a glint of light reflected off a window, or see a rowboat on the glassy lake, or detect the reassuring presence of a plume of smoke in the distance, implying a hearth somewhere. Metzger’s work traffics with the sublime and puts us more in the realm of Bierstadt and Thomas Moran than Church and Kensett.

In “Mountain and River” (2014), we can just make out the distant silhouette of a mountain pushing up through the reassuring horizon line. But the painting’s drama is in its clouds. Metzger’s clouds are shapeless but energetic materializations of water vapor. That sounds very clinical but it’s important to remember that his clouds are not those of Constable, say, or Thomas Cole: they don’t look like anything. There is something resolutely non-metaphorical about them. Metzger doesn’t need and doesn’t utilize the pleasures of line and draftsmanship. His clouds function as veils, occupying space on his canvases to keep us from seeing what might be behind them. When the clouds change color, as they do in “Mountain and River,” it is hard to tell whether they are breaking up, suggesting just a bit of blue-grey sky peeking through, or whether the darker portion is just another, grey-blue (and wetter) layer. It is reasonable to think that the purpose of the clouds is to remind us of one of modern painting’s great formal issues: when we look at a canvas, are we seeing an illusionistic representation of a deep space which, in this case, the clouds have obscured, or are we looking at a flat painted surface, where the notion of something behind another thing is a mere illusion, however convenient or habitual?

Metzger’s work calls attention to the physicality of art in other ways as well. About half of the works hanging at Miller are painted with colors he made himself out of ground slate, marble, iron, and lapis lazuli. When asked why, Metzger explains that it is not about nostalgia or even control, but to help focus on the tension “between illusion (ie using paint to create something that is not) and materiality (ie the paint is actually a combination of a beautiful stone and silky oil).”

European landscape tradition imagines that we are situated on a fixed place looking out towards the stabilizing and reassuring presence of a horizon line somewhere. Metzger’s “Atmosphere XI” (2015) takes us one step further. It feels as if we are looking directly up, rather than out, at veils of mist and cloud, without line and without gravity. (There is so much moisture represented in this show that just looking at it must be good for your complexion.) As with “Mountain and River,” it is not clear whether we are looking at the sky clearing, or clouding up. As I read this work, it is a daring reminder of how much we usually depend on a horizon line, whether present or even just implied, to ground a painting, however abstract, and orient the viewer. We are still earthbound—I get the feeling that my feet are still on the ground—but in a dizzying and liberatory way. A picture like this speaks directly to the “paradoxes” Metzger writes about in his Artist’s Statement, where he says that his work represents “forms dissolved in haze, atmosphere, and light, yet substantiated.”

In an email, the artist comments on the wide range of sources and models available to him: “references and influences can be found within the work itself (such as nods to romanticism, Song Dynasty painting, Luminism, lyrical abstraction/color field painting, etc.).” Think of the swirling atmospherics in late paintings by J. M. W. Turner, the lyrical skies of Martin Heade, the second generation abstractions of Helen Frankenthaler and perhaps especially Jules Olitski who, like Metzger, made an important series of paintings that left almost no trace of a brush stroke. But in this showing of his work, Metzger seems to have been particularly interested in seeing the ways that his vision is in conversation with the great works of ancient Chinese paintings. “Occidental Voids” (2015)—the least scroll-like of his Chinese-inflected works on show—is an excellent place to take the measure of these issues. As the painting’s title suggests, the painting sets out to contemplate the Asian sublime with western eyes. Though it might be about torrents of rain obscuring the shapes of the land, it might also be the morning sun burning off a fog. Once again, the painting is dominated by veils of pale color that seem both to conceal something hidden in the topography and yet to be the true subject of the painting. The masses of color at the center read both as a curtain and as a centerpiece: they are all we need to be paying attention to. There are suggestions of a hilly landscape towards the bottom of the painting, but they are among the least readable landscape features—the most like blots—of any of the pictures in the show. There is a bleached quality to the center of the painting; by the time we have gotten to Metzger’s 2015 pictures, his 2014 works seem positively gaudy by comparison. As the title of one of these later works suggests his color range runs from “Slate to Ochre.”

Part of the appeal of Asian painting to western eyes has been the ways it indicates pictorial depth. When the painters trained in the European tradition saw Chinese landscapes, they had a revelation: the devices by which western artists exerted themselves to suggest the recession of space and the connections between foreground and background were unnecessary, uneconomical, and a distraction. The Asian pictorial tradition happily suggests that some things are behind others, and that there can be an astounding amount of space to traverse. How else would all those boats filled with exiled poets make their melancholy, contemplative ways to new homes far from the corruption of worldly courts? But they do not accomplish this by employing western schemes of perspective—yet things still somehow make their way from the back towards the front. As a colleague of mine observes, Chinese art is interested in essences, not likenesses, as is Metzger. “Su Shi’s Passage” (2015)–named after a Song Dynasty exiled courtier, poet, and calligrapher–features a waterfall, or perhaps a river, which suggests how something in the distance makes itself known to something closer to us. What is our position as a viewer? According to the “occidental” ways of figuring space, we would think of the voyeuristic eye of the painter, looking out his window at some civic space—the interior of a church or a public square somewhere—recording what is seen with the geometric optical conventions that we call “perspective.” Perspective gives us a sense that the artist is both removed and yet still connected to other citizens. It anchors the painter’s eye. But not in Metzger’s work. There are trees that are going to have to be dealt with, but not from where our point of view is located. They are more or less stacked on top of each other far below us. It is as if we were in a drone, alertly hovering for a moment over a complex space and changing we cannot tell too much about, ready to plunge down into it all—or just to soar away.

Metzger’s remarkable paintings were exhibited in a two-artist show at the recently refurbished Miller Gallery space in Hyde Park Square. Reopening under new ownership with fresh and friendly Gallery Associates and a thoughtful new Director, David Smith, Miller now hosts a very contemporary-looking space for one of Cincinnati’s oldest continuously operating art galleries. The other artist on display was Jonathan Queen, whose work might initially seem as if it was not being shown to its best advantage being paired with Metzger. Queen’s paintings are small and sober while Metzger’s work is exuberant and demands space.

But it seemed to me that Queen’s work could be seen as being in profitable conversation with Metzger’s if we think of it as representing one of the rival arcs of American visual culture. Queen’s work is part of the American tradition of the hyperbolically realistic and powerfully-restrained late nineteenth century still lifes of John Peto and William Harnett. This tradition represents the stream of American art that believes that an artist’s first duty is to look hard at what’s real. It is both adorative and skeptical about its subject matter, and even about the consumer of such objects. This is the tradition of the American artist who feels obliged to start with what is seen, even if what is being seen is commercial, mundane, and literally plastic. But to an eye like Queen’s, if you look hard enough at something in front of you, you might just see through the tawdriness of its materials and reach an understanding of what it’s capable of doing and why you might want to be careful when in its presence. In Queen’s best work, the mundane unfolds to reveal the uncanny.

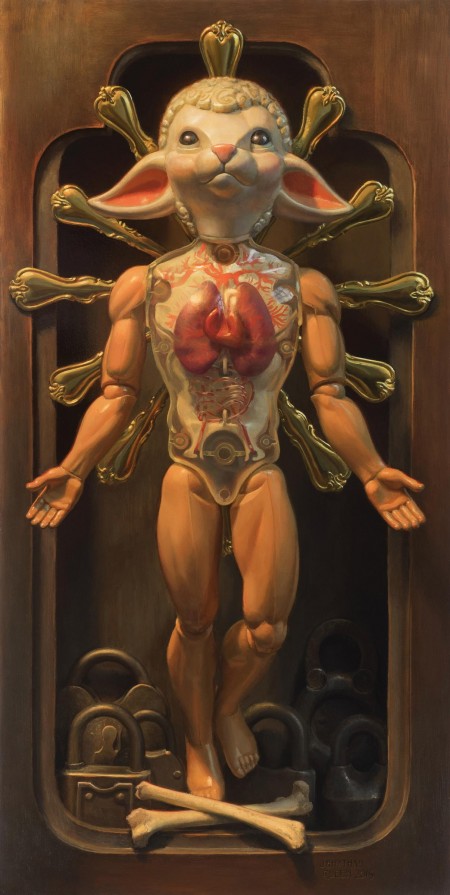

Queen’s show in the Miller’s smaller gallery included a wall’s worth of sketches for the paintings that ended up on Cincinnati’s new merry-go-round in Smale Park which were reviewed when they were on display last year, a couple of interesting tabletop arrangements and three plastic still lifes, all figurative and variously monstrous–in a good sense. “Headstrong” (2015) features a portrait of a nineteenth century athlete with a prodigious moustache framed in an oval as if it were a hundred year old tintype, except that the figure is clearly plastic. There is something fierce and unforgiving about it, as if it were an idol for a post-apocalyptic cult. What if the mute, hulking figures at Easter Island had been redesigned by the toymakers at Hasbro? “Awakening” (2015) is even more like a cult object. A rabbit-headed human with its chest laid bare to reveal its organs is stepping out of a wooden box. It is surrounded by a radiating assemblage of silver spoons and is stepping gently over a pair of crossed bones behind which we see some half a dozen padlocks. Perhaps it is something divine returning to life, stepping forth from a tomb. Part of the piece’s appeal is that its parts are more coherent than the whole; any two or three parts of it make good enough sense, in a mysterious sort of way, but the whole, I think, defies easy categorization. It is not easy to tell whether the overall feel of the piece is intended to be divine or demonic. It seems satiric without being over-determined: perhaps part of the point is that we love our toys, our miniaturized worlds, on the condition that we don’t inquire too rigorously about just what they mean, or how insistently they are capable of meaning it.

I don’t think that Queen is throwing up his hands and walking away from creating meaning. I think he has a good eye for the strange and particularly for the strangeness in our commercial, disposable, hyperbolically iconic culture. “New Light” (2015) is a portrait of a plastic Big Boy. It certainly reminds us to wonder about just how strange a representation of the human form a Big Boy is. We are below it, looking up, suggesting that there is something gigantic about it, which makes its almost appalling cuteness even more strange, like the monstrous Pillsbury Dough Boy in Ghostbusters. I liked that it was evasive—it won’t meet our eye—and its blank and slightly smirky smile is about something that it won’t share with us. An interesting final dimension to these paintings is that Queen is painting things that have already been painted. They are, that is, artifacts that are being re-represented. Despite their sly sense of humor, Queen’s paintings seemed in part a warning to pay more attention to the artwork we might find ourselves surrounded by in our daily lives. As idol-makers have known for millennia, there are powers in inanimate figures waiting to be set free. Unless they’re no longer waiting.

–Jonathan Kamholtz