According to the Speed Art Museum, Picasso to Pollock: Modern Masterworks from the Eskenazi Museum of Art showcases the impressive early 20th-century art collection owned by the Eskenazi Museum of Art at Indiana University. It covers the breadth of nearly every major artistic movement that occurred between the years 1900 and 1950 in Europe and America. During this period, traditional notions and expectations about making art were completely upended as artists explored radical new approaches to color, form, and content. Boundaries were pushed via revolutionary new ways of thinking, expressed through such movements as Fauvism, Cubism, German Expressionism, Dada, and Surrealism.

The exhibition serves as a basic primer in early 20th century modern Western art . . . with emphasis on the creative process and artistic experimentation, especially as the century progressed.

This exhibition is the first in a collaboration between the Speed and the Eskenazi Museum that will span the next five years. The Eskenazi is currently getting a remodel relative in scale to the one the Speed received a couple years back, and is sending its collection out on loan in the meantime. Thus, the museums are taking part in the contemporary practice of shuffling and trading collections in lieu of acquisition due to budget cuts. All well and fine.

The exhibition is arranged as chronologically as Jenny McComas (Eskenazi’s curator of European and American art) and Erika Holmquist-Wall (Speed Museum’s Curator of European and American Art) could manage— which is a huge curatorial feat considering, as they so aptly put it, “The first half of the twentieth century witnessed more sweeping change than the previous 1,000 years of human civilization combined.” Holmquist-Wall and McComas charged themselves with creating an exhibition that covers the fifty years in art—scratch that, the fifty years in history— that changed our contemporary world. The galleries are divided into the following categories: Cubism, Expressionism, Dada and Surrealism, Wars and Revolution, Urban Life, The Figure, and Abstraction. Note, I didn’t observe any works from the Impressionists or Futurists—artists working in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and also artists that I consider part of the modernist brood.

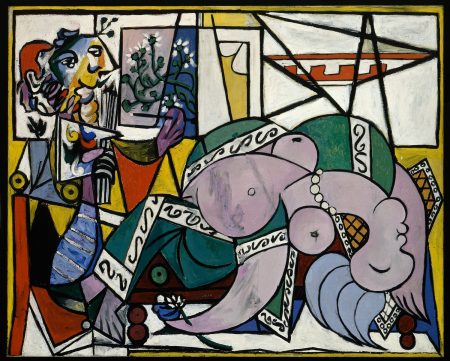

Entering the first gallery of the exhibition, Cubism, the most recognizably Cubist work that you see is Pablo Picasso’s The Studio (1934)(fig 1.), located on the back wall. Perpendicular to it is Georges Braque’s The Napkin Ring (1929). Paired with each gallery or stylistic category, the Speed introduces a historical context and definition of the style, as is museum common practice. Here, the audience is reminded that “Cubism can be linked with Albert Einstein’s theory of relativity, which dates to the same period, and demonstrates that nature is not absolute, and no single interpretation of it—whether artistic or physical—can grasp its totality.” I often forget this as well, remembering instead larger historical correlations such as the World Wars or Industrialization. This reminder is interesting because, yes, Einstein taught us the above, but he later went on to cultivate ideas around the fourth dimension, still being elaborated within quantum physics. In 1952, Einstein proclaimed in Relativity that, in summation, the separation of the past, present, and future was a successful illusion; in reality time was non-linear and relative to the individual experiencing it. Though I recognize this later idea wasn’t one that had any influence on any of these works—I can’t help but consider the pragmatic destruction of perceptual space in Cubist works as an interesting, and eerie, coincidental prerequisite to our ideas around the fourth dimension.

In retrospect, the museum had a great opportunity to fully utilize this Einstein paradigm they put forth to connect history with its present context. For example, in the Expressionist gallery, the Speed describes the Degenerate Art Exhibition of 1937 (the infamous traveling exhibition arranged by the Ministry of Propaganda to destroy the reputations of modernist artists). To add, they do mention that in 1935, a purge of German national museums began and over 16,000 works of art were confiscated with the intent of sale at auction, or just plain ole’ burning. Where they missed the educational mark was in the lack of reminder that, yes those things happened and they were atrocities. But Nazi officers also stole a lot of these works for their own personal collections, and a lot of those 16,000 works never ended up going anywhere because the war ended—and the international market is still dealing with, and messing up, the repercussions. (For example, a Gustov Klimt piece was returned by Austria to the wrong family last month).

The Speed had the opportunity to inform the public that we are still dealing with the repercussions of this era of our dark, dark, history that feels so frighteningly current—and yet it didn’t. After all, if we are here to teach, let’s make our teachings relevant for our public that might view drawings and lithographs from 1940 as relics of a bygone time—because they aren’t.

None the less, this exhibition that has over seventy works has plenty of other muscles to flex. To start, the charming little lead drawing by Russian Cubist Kazimir Malevich (1878-1935), Peasant Scene (fig 2). Malevich’s charm is in his modesty, where Picasso’s lies in his brazen masculinity, if you find that quality charming. The bulk of the collection and thus exhibition, lies in the areas after Cubism and before Abstraction. This is clearly where the Eskenazi Museum holds the heft of their Modernist works, and there were some gems and names to get excited over—but in commonality with a lot of Museums in this region of the country— none of the pieces were substantial works by the artist. Money shouldn’t effect curation, but it effects acquisition, which obviously effects curation.

There were absolutely some highlights: Seeing Egon Schiele’s work is always a pleasure, though placing his drawing and a drawing from Edvard Munch next to each other lumped the psychologically problematic artists together—reading as a sort of curatorial asylum, if you will. I was thrilled to see Emile Nolde’s Nudes and Eunuch (1912), and there was an ink drawing across the way from it by Ludwig Meidner, The Bar, Wilmersdorf (1915) that was a hurried depiction of the romanticized bar scene of the turn of the century that I found really lovely, and a great artifact from Germany’s Weimar cabaret sub-culture. In the Dadaist and Surrealist gallery I was happy to find one of the editions of Man Ray’s Gift (1921) and The Enigma of Isidore Ducasse (1920). I’ve always considered Man Ray’s particular blend of prodding wit and strait forward abrasiveness for his audience interesting; he’s vastly underrated. He always felt like the Vito Acconci of the Surrealists—critically adored and deemed absolutely cringe-worthy by his peers. There’s a drawing by George Grosz— whose sensibility I always enjoyed. There’s the overpowering example of despair: Place of Darkness (1943) by Abraham Rattner (fig. 3) grouped into the area designated to those artists particularly distressed over any of the myriad of wars and atrocities plaguing the planet from 1914-1945. In Rattner’s case it was the Holocaust. Rattner’s use of color in this work is psychological, articulate, and overall—terrifying.

After this are the Urban Life, The Figure, and Abstraction galleries. These frankly don’t contain anything too exciting. The Jackson Pollock—yes, I’m implying that there is once again one work from the exhibitions’ named artists—consisted of the series of six untitled silkscreen prints on paper in 1951. Access to the complete set is rare, as only three museums in America have all six prints. These don’t have much circulation, and honestly, Pollock spent three years making drip paintings. They aren’t his all; and if anything they’re a reminder of a mind fallen to sadness in a way that’s way too relatable. The Abstraction gallery overall was a bit disappointing—especially when on the other side of the wall in the Speed’s permanent collection are works by Helen Frankenthaler, Gene Davis, and Louisville’s own Sam Gilliam.

To summarize, I read other reviews of this exhibition that came with warnings about a“sense of whiplash” after viewing. It’s true, there is a lot of content here—with little room for substance due to quantity and necessity of context. “Picasso to Pollock” could have used a bit of editing. In the hope of educating the public, they seem to have removed relevant contemporary information—why this work is important here and now and not some antiquated stuff in a museum. In addition art history is fascinating, especially this era of art history, due in part to its mythic correlations. For example, it’s rumored that Jackson Pollock wandered into the MoMA in 1939 after having visited his therapist about his drinking and found their exhibition of Picasso’s work, Picasso: Forty Years of His Art and felt encouraged to evolve his style further. In the early 1940’s we see him begin to move toward his famous drip painting; these sort of facts are what bring an exhibition of this size and caliber full circle.

“Picasso to Pollock: Modern Masterworks from the Eskenazi Museum of Art at Indiana University will be up until January 13th, 2019 at the Speed Art Museum in Louisville, Kentucky.

–Megan Bickel