On view through April 5th at the Weston is an exhibition by a Cincinnati native and current New York dweller, Todd Pavlisko. Pavlisko’s “Pop Supernatural,” is – as you might guess – guided by conversations with popular culture. The Weston’s two floors organize the exhibition. The entrance level floor holds a few different threads, while the lower level gives way to tall Pez dispenser statues with famous faces – a small hall of fame of sorts. With his artistic interest in popular culture, Pavlisko generates dialogues that explore the economics of art, the social politics of time and human influence and the tensions between artistic, scientific and popular cultures.

On the entrance level floor, the economic dialogues here feel the most slippery. A cluster of neon light sculptures hangs from the ceiling. One says “The Birth of Cool” while another reads “Milk and Honey.” Within the tangles of each neon sculpture sits a pair of women’s designer shoes. My initial reading is that Pavlisko wants to criticize rich people who like to read Rupi Kaur’s bad poetry and listen to Miles Davis under the guise that they appreciate the sophisticated arts of jazz and poetry. The sculptures feel, on one hand, counter productive in their protection of the fancy footwear and vapid in their judgments (if indeed they are trying to criticize artistically economic vanity). On the other hand, they don’t quite seem to know what they want to say beyond the surface. Likewise a giant, hanging basketball constructed from loose change (a part of Pavlisko’s ongoing series “All the Money I Found in a Year”) is interesting in its long term scope, though it doesn’t seem to remind us of much more than the fact that art and time cost money. He seems to want to tell us about the realities of capitalism rather than reflect on them. His Pez dispensers ruminate more effectively.

Gold-plated coins, Plexiglas

¾” x 473/4” diameter

Photo courtesy of the Weston Art Gallery

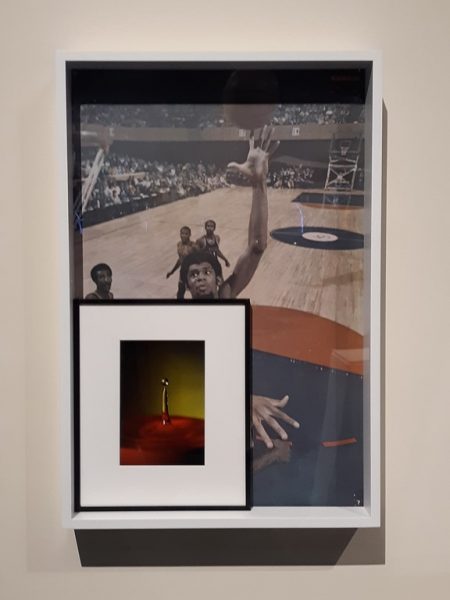

The economically conglomerated basketball does allude to the strengths of the exhibition, however, as it can guide us toward thinking about time and culture. Time manifests here in snapshots and legacies, which give way to a collection of tensions. On the wall hangs a collection of blown up basketball photographs overlaid with photographs by M.I.T electrical engineer Dr. Harold Edgerton. Kristin Rogers (who wrote the informational plaques) writes, “Edgerton’s technologies and genius would go on to influence the innovations and equipment developed to meet culture’s ever increasing demand to capture the micro-blinks in our lives—including the speedy action of professional basketball’s greatest moments.” The tension here includes celebrations of both each major cultural universe. Sport is celebrated. The celebrity of Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, an influential and popular athlete, is on display with these snapshots of enduringly impressive displays of athleticism. The scientific images, placed on top of the sports images are never obscured. Some of the athletes are obscured, reminding us that these experimental, what appear to be smaller moments endure as well. By placing the two in tension, Pavlisko might also be arguing for reverence of scientific culture over sport culture.

Vintage NBA poster layered with framed “Water Dropping into Water”, 1978 by Dr. Harold Edgerton

Dye transfer print, 20” x 24” (Edition of 25)

Signed original from Edgerton estate

37” x 25” overall

Photo courtesy of the Weston Art Gallery

The counterparts to the images are sculptures of basketballs wrapped with violins. Rogers writes “the dual (duel) presentation of frozen basketballs, draped with silent violins, complement the drama captured in the stilled moments of the wall-mounted works as they ensnare kinetic force and distill it into a montage of anticipation-building.” Her reading seems to imply a certain coexistence of the two – as I think was supposed to be implied with the images – though I want to point toward the tension present where she writes (duel). Perhaps this could be another celebration of basketball, though I’m more inclined to read it as a friction between sport culture and art culture. Rather than coexistence, the basketball rather seems to be warping and punishing the violin. The sculptures allude to tension between the two cultures. Further, the use of violins – an instrument associated with classical music – alludes to time’s role in the decline of older forms of culture. Though the hope of sports and arts coming together is admirable, the tensions therein, might be more realistic and more interesting in their implications.

2014-15

Carved wood, stainless steel, NBA basketball

12” x 14” x 14”

Photo courtesy of the Weston Art Gallery

Cultural endurance and impact through time particularly emanate from the Pez statues that occupy the gallery’s lower floor. I previously called it a sort of Hall of Fame, which is perhaps contextually appropriate in an exhibition with sports iconography. The six faces on the Pez statues are Rosa Parks, James Baldwin, David Bowie, Princess Diana, Frederick Douglass and David Hammons. Interwoven throughout the towers are neatly organized sledgehammers resting on bags of sugar. Rogers writes, “these sledgehammers rest quietly hushed upon their saccharine pillows with the calm cry of destruction averted.” Sharon, who works in the gallery, shared an interpretation of them as symbolic of how each figure broke through to sweet success. I like to think of the six as sledgehammers of culture, though I don’t think we should be distracted by those symbols from the work that the statues themselves do.

Carved wood, metal, lock, undisclosed time capsule materials

78” x 18” x 18”

Photo by John Carrico, courtesy of the Weston Art Gallery

These statues, like the work on the entrance level, interrogate relations between different socially influential culture realms. This is a group of esteemed historical and artistic figures. They each have time-honored legacies that might evolve as time passes. The statues prompt us to think about what these people and their legacies mean. Pavlisko wants to ask about the nature of reverence and how we go about monumentalizing and remembering these legacies. I also think interpretations can vary depending on how we contextualize these specific figures together. David Bowie, for instance, is no doubt a pop icon. Known for his constant generic and visual evolution, Bowie challenged generic ideas of rock and roll – to name only one genre that he worked on. Bowie was also an influential challenger of social norms. We might consider his greatest influence: his musical contributions or his deconstructions of masculinity? Baldwin, another queer icon, is important to me personally as a great writer, though he might endure because of his contributions to discourses on sexuality and black rights.

Carved wood, metal, lock, undisclosed time capsule materials

74” x 20” x 16”

Photo by John Carrico, courtesy of the Weston Art Gallery

A more important question that follows, naturally asks if these people should be on Pez dispensers? Is this appropriate? Each tower has a locked door on the side with no allusion to what might be inside. Should we be interrogating the interiors of these people? I think Pavlisko wants to ask interesting questions about reverence here. Do they belong in museums, or should they be democratized by something so common as a Pez dispenser? Might that democratization be cheapening? I can fathom Bowie realistically on a Pez Dispenser, but I can’t help but wonder if it’s a little disrespectful to put someone like Rosa Parks on one. I think Pavlisko wants to ask if we should allow important figures to be reverenced by simplicity and what dimensions of culture decide who is, and isn’t, important for culture. I also wonder if it’s been long enough since Parks’s time to start changing the way we reverence her. Perhaps, in a culture in which racism is very much alive, if people like her should remain in places of seriousness. No matter how you answer these questions, though, I think this is where he alludes to his economic interests most effectively. It isn’t forceful like the neon and shoes, but it similarly reflects on the reality that people – like art – will be commodified as time negotiates their legacies. Museums and monuments, like Pez dispensers, have economic boundaries and Pavlisko wants to question how our considerations of culture and legacies fit within or without those economic boundaries.

–Josh Beckelhimer