“You mean Messiah?” JJ Brine hastily corrects me when I quizzically point at the two McDonalds logos on Vector Gallery’s wall, probing him about his interest in selectively appropriating capitalist imagery. It is the day before JJ Brine’s opening of the newest rendition of Vector Gallery, a space that has traversed a multiplicity of incarnations, from Manhattan’s Lower East Side, Los Angeles’s Beverly Blvd., Miami’s Art Basel and, currently, Grand Street in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. The Grand Street Vector Gallery sports lustrous silver paint, a futuristic chrome interior, and a myriad of appropriated capitalist imagery, neon signs, and disfigured mannequin torsos. I have entered Vector Gallery on a frigid evening to meet and interview artist and Vectorian brainchild JJ Brine prior to the subsequent day’s grand opening.

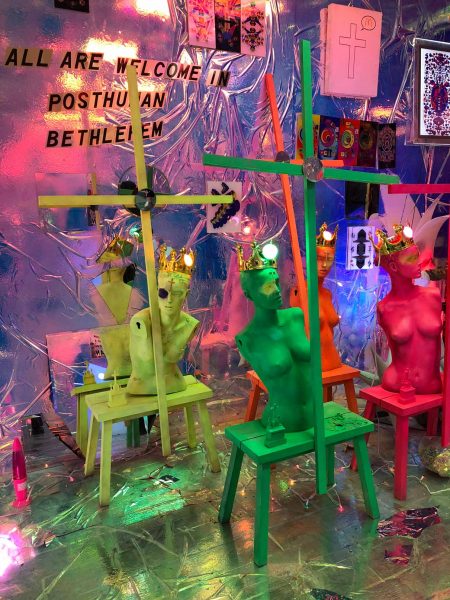

I encounter several torsos and heads spray-painted vermillion, verdant green, and bright yellow, resting on stools and serving as idols before three crosses, the paint matching the mannequin figures. “The Mother of God” reads the text on the back wall, with small depictions of The Virgin Mary and Christ framed by vivid bulbs and fractal-laced posters.

JJ Brine refers to himself as “The Crown Prince of Hell,” and Vector Gallery has been dubbed “The Gallery of Satan”. However, to circumscribe JJ Brine’s project as a self-interested art-cult shock project would be to dismiss its posthumanist ethos and palpable energy. Brine is not interested in thwarting audiences and the newest Vector Gallery is less based on “shock,” with a pronounced lack of the images of Charles Manson that garnered Brine a slew of past criticism (Sunderland, Mitchell). Brine has capitalized on negative space by keenly utilizing mirrors on all the interior walls to create an all-absorbing “liminal interspace” where the self is transfixed with capitalist imagery and Christian iconography, pleading parallels between self-actualization and the cult of self. A large “Dior” sign gleams against the back wall, fitted behind a cavernous white dome. Vector Gallery’s hyper-maximalist decorum traverses the aesthetics of post-net art and reappropriative postmodernist modes. Iconoclasm and orthodoxy are visually sublimated via neon and chrome displays, transformed from their original hierarchy re: religious institutions into the pop-art politics of affect-based installation.

Vector Gallery has captivated art critics from diverse backgrounds, with The Wild Magazine’s Cody Ross extolling Brine for “inverting all manner of orthodoxy” while JamesMichael Nichols compares Vector Gallery to Warhol’s Factory – a blatant parallel considering the penchant for reflective surface and hosting avant-garde musical performances. Nonetheless, Brine participates in dozens of appropriative modes and Warhol’s pop-art practice is solely one; passages from Gnosticism and Kabbalah accompany what Brine has facilitated into a seminally spiritual place, which is fitting considering that Brine forwards a religious accompaniment: Vectorianism. Vectorianism, identified via the deity ALAN (who is praised in several lines of text across the installation walls), presents an aggregate of Abrahamic religions.

The subsequent night will host several performance artists who invite audiences in ritual readings and practices. Brine smarmily wrings his nose when I make comparisons between Vectorianism and cult ideologies/figures past (David Berg, Jim Jones, etc.) yet brazenly predicts that the world will end in 2033 via a “mass return to ALAN.” The level of sincerity regarding Vectorianism and Brine’s faith is difficult to gather, though it is quite possible that he is posing a Brechtian performance of New Sincerity, blending postmodernist criticism of groupthink alongside the genuine belief in poignant communal healing – a central tenant to the mass readings that Vector Gallery audiences perform alongside JJ Brine and company when the gallery walls are open for Happenings-style events.

Despite the fact that the gallery is generally closed to the public, the brilliantly illuminated space is visible to outside audiences through gargantuan glass walls. The chrome interior, glazed idols, and accompanying texts are all visible as, in Brine’s own words, the gallery “empty or full, is alive.” When asked how this reification of Vector Gallery discerns itself from past projects, Brine comments that “This one is not terrifying people, they are delighted…in the past people would scream with terror,” due to the implicated rapture and alien imagery. One of the most interesting points of our interview is when Brine comments that “someone wrote Satanic scum” and adorned the outside with several crosses a few days prior, which he subsequently painted over because he “…didn’t like the shade of yellow” and the way in which the crosses were drawn. Despite being an invitational space of mutual discourse and fluidity per-Vectorianist communalism, it would appear that JJ Brine retains a cult of character during these moments, where he either deflects theoretically involved questions or defends authoritarian rigidity with aesthetic prowess. Curious about how a space designated to break Abrahamic religion’s traditional polemics can reject any form of critical participation I ask him whether such action, albeit vandalism, participates in Vector Gallery’s fundamental crux. Brine shrugs, commenting that he “noted it, I took a screenshot of it,” showing me images of defacement on his phone.

“Why Messiah?” I inquire, attempting to elucidate whether Brine has selected iconography that is immediately recognizable, corporately fueled, or purely aesthetic. “Because that’s what I think it means and I can culturally reapproriate McDonalds all I want to, and make it my religiously charged symbol…it gives me religious and psychic power, and anyone else who wants to.”

Brine notes that he doesn’t see McDonalds as an inherently capitalist logo and quips that “we are all Jesus Christ,” pointing at text bisecting two walls that reads this line. An amber “M” and crimson “M” frame the text “JESUS LOVES U LGBTQ.” Brine has reappropriated icons from McDonalds, Maybelline, and Dior with the intent to empower disenfranchised parties through apportionment, a nod to the sociocultural implications therein. At this point, it seems relevant to note that Brine is well-versed on sociopolitical matters, having pursued an international affairs-based education, attending graduate school at the American University of Beirut, serving as an assistant to the National Security Advisor Brent Scowcroft, and interning for the American-Turkish Council. Disenchanted with politics and international affairs, however, Brine comments that he is pursuing the goal of “making people happy” via the cathartic response of his communal invitational – Vector Gallery.

JJ Brine describes how he and fellow Vectorian artist, The Oracle, set to disembody the United Nations at the SpaceX Los Angeles Open by commemorating Pangea as its newfound replacement. Pangaea refers to the Late Paleozoic supercontinent, a united structure that geologically embodies the interconnected catharsis JJ Brine hopes to actuate with Vector Gallery.

The cult of personality emerges, nonetheless, as Brine guides my fiancée (who has been curiously photographing the Vector Gallery interior) and me into a ritual chant. “The Vatican has pardoned Satan, I finally bowed down to Adam…Jesus Christ is coming soon not to Judge, but to restore us all, to ALAN.” Brine then continues to describe Vector Gallery’s early beginnings, having hosted Nico (from the Velvet Underground) performances and other artists’ work to now self-installing all the featured religious tryptichs, re-appropriated industrial signs, and neon lights, mirrors and chrome decor as one continuous installation piece.

JJ Brine rejects the terms and cannon of aesthetic theory and philosophy of art, preferring a more personal motive in art-production. This puts us at inherent ends – I am an art historian adept with theorizing and he a post-humanist who rejects my deferrals to Donna Haraway’s biopolitics and Carey Wolfe’s bioethics. “I am the Minister. To create the art, make the country, to identify post-humans, and mechanize telepathy” boasts JJ Brine, “I thought I invented the term post-human, I came to the term not through study.” Nonetheless, I believe that Vector Gallery’s catharsis – via communal exchanges, chants, ritual and appropriation – fits within Haraway’s posthumanism. JJ Brine mentions the term “cyborg,” a crucial component of how posthumanism has developed in the last few decades. Haraway’s cyborg is foremost a feminist project located in the desire to reconstitute identity politics, particularly as it concerns assumptions about gender norms and representation (Miah, Andy). A second reading of Haraway and, in turn, Vector Gallery, involves understanding how post-humanist ideas have become central tenets for advancing the notion of a post-gender world. Haraway is interested in “how we become posthumanist,” challenging the vein of posthumanism that expresses biological transgressions as a means for utopian evolution with a preference for social transgression (Haraway, Donna). Similarly, JJ Brine rejects a technology-driven understanding of posthumanism, privileging art-production and communalism to techno-human integration. “I evolve past being human by making art, where the organic and synthetic technologies are uploaded metaphysically.” This is well characterized by the aesthetics of Vector Gallery, where one is forced to consider the psychoanalytic modality of self via the Mirror Stage – the moment at which people recognizes themselves as autonomous entities. By pairing the self vis-à-vis the framework of a sea of mirrors crowned by capitalist entities of production, JJ Brine has, willingly or not, traversed the modes of a typical gallery space and introduces a myriad of metaphysically dense questions.

Vector Gallery is not exempt from its cult of the personality, as JJ Brine proudly declares himself Minister and offers 2033 as his eschatology of End Time. Nonetheless, the Vector Gallery space offers unique perspectives on post-humanist sociocultural motives. Truly a single artwork that bounds the walls of a gallery, Vector Gallery is psychologically dense and offers a multiplicity of readings. The aesthetics of the future are markedly pronounced yet difficult to pinpoint with any one message. I urge all those traversing Williamsburg to visit 951 Grand St, Brooklyn, NY and facilitate a visit with JJ Brine by contacting [email protected] for an ethereal art experience, entirely unique from the New York art semblance of art-market savvy Chelsea Galleries and museum megaplexes.

Ekin Erkan is a free-lance writer, senior art history student, and video artist studying at University of Cincinnati, DAAP. My research and art practice concern new media, virtual networks, and affect theory.

Works Cited

Haraway, Donna Jeanne. A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist-Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century. Georgetown University, 2009.

Miah, Andy. “Posthumanism: A Critical History.” Medical Enhancements & Posthumanity, Routledge New York, citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.693.6755&rep=rep1&type=pdf.

Nichols, JamesMichael. “JJ Brine’s ‘VECTOR Gallery’ In New York City.” The Huffington Post, TheHuffingtonPost.com, 20 Jan. 2014, www.huffingtonpost.com/2014/01/20/vector-gallery-jj-brine_n_4619179.html.

Ross, Cody. “Vector Gallery Opens in L.A – The WILD Magazine.” The Wild, The Wild Magazine, https://thewildmagazine.com/blog/vector-gallery-opens-in-los-angeles/.

Sunderland, Mitchell. “New York’s Satanic Vector Gallery Is Closing.” Vice, Vice Magazine US, 5 Apr. 2015, https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/dp54vx/satans-art-gallery-405.