Robert Flischel is someone who can’t get enough of looking. He speaks of seeing abstraction in porches, in tool heads, in 300-year-old pavement – “all the lines” – and says he learned long ago that “the body is an abstract composition.” He talks of “the series of lines that work underneath the picture’s composition within the rectangle,” and adds “I respect the rectangle, the four corners. Nothing gets in.”

Flischel has been a photographer in Cincinnati for forty plus years. The fourth edition of his Cincinnati Illuminated: A Photographic Journal is out this year and includes views from the 1990s up to just about now. He is fascinated with shape, with relationships between shapes, with light and shadow, and displays them all in page after page of stunning color photographs. People are not his subject here. The environment in which they live, man-made but enlivened by nature, is what his camera has recorded.

He says, however, that he considers himself primarily a portrait photographer, with the caveat that photo journalism allows him to “define the landscape” through architecture and landscape photographs. “I enjoy creating art photographs,” he told me. As well he might; there are handsome results. We talked in the Flischel home in a room filled with projects underway, the walls here and elsewhere enlivened by Robert’s wife Jackie’s abstract paintings. This is a household attuned to visual experience.

A life-long Cincinnatian, Flischel was a sociology major at Xavier University, with art on the side -”started off as a watercolorist at Xavier” he says, graduating from there in 1971. Kazik Pazovski, a portrait photographer, was a strong early influence. Further studies took him to Edgecliff, then in the old Edgecliff mansion at Edgecliff Point. Sister Ann Biersdofer was Chidlaw Artist in Residence at Edgecliff, which he remembers as “a great environment for learning. High ceilings, large spaces. . .” He is quick to say that he studied with some very good people and also looked, and looked, and looked some more. John Marin’s watercolors were an influence and the Austrian-born, New York-based photographer Ernest Haas made a strong impression on Flischel through his book, published four times and redesigned each time, every picture dated, beginning in 1971. Flischel himself has done something of the same with Cincinnati Illuminated.

This handsome book shows us familiar things: the river, the architecture, Findlay Market, Coney Island, the parks, the suspension bridge, the things that give the city its own flavor. Its generous size allows for spectacular prints – Union Terminal is a mysterious dark shape against an evening sky, fall foliage in Burnet Woods becomes a blanket of color seen from the tower of Hughes High School. New work enlivens each new edition of the book.

Flischel’s publications include a collaboration with other photographers for Messages of Glory, subtitled “The Narrative Art of Roman Catholicism” and his own photographs for An Expression of the Community, about art and architecture in the Cincinnati Public Schools, with essays by Anita Ellis and Walter Langsam. Some of these photographs must have presented problems of access for the photographer; architectural details are not necessarily eye level. “Shadows,” he told me, “are important when photographing reliefs.” So if there’s not a shadow, someone must make it happen.

Immediately after college the photographer-to-be had gone to work for the Cincinnati Association for the Blind and Visually Disabled but in 1977 he opened Robert Flischel Photography and formally made that his primary occupation. “For portraits,” he said, “you need to engage the subject. I still love doing them. Pushes my brain around.”

Some of Cincinnati’s early artists, who themselves never touched a camera for artistic ends, have been continuing influences on how Flischel sees the world. “We have similar interests,” he says of E.T. Hurley’s etchings, Carolyn Williams’ drawings. In terms of more recent influences, he mentions Tom Schiff’s Cincinnati Panorama. “You start to see how the brain works with color.”

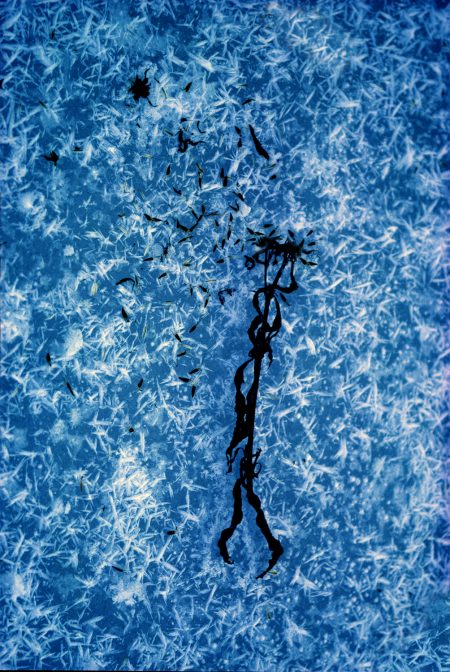

When artists talk about how they think, it can be surprising as well as informative. Flischel is interested in “our culture and the machines that make it” but nature is an equally strong element. “A wet sycamore leaf is transformative. Old apple leaves are a visual pleasure. Color harmony is important to me.” He also mentions, fondly, still lifes, landscapes, abstractions -“which I love,” he says of the latter – paint chips, salt stains on asphalt -“That’s gorgeous. Have to say so.” He believes, he says, “in something out of nothing. Unexpected repetition of shape. It’s all fair game.”

Flischel will continue to look at Cincinnati through his viewfinder and continue to show us what we might miss on our own. “You have to connect the unconnected to understand today,” he told me. In a sense, that is what his pictures do. In fact, he’s been taking photographs long enough that they help to understand yesterday too.

–Jane Durrell