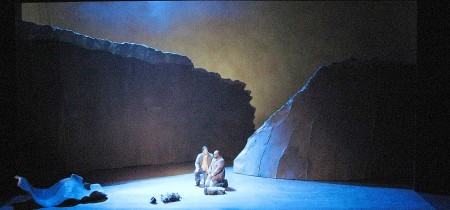

Artists make things. They make stories, they make pictures, they rustle around through possibilities, try something different, emerge with what may be a new look for some old thing. A particular line of work – that is in fact making things – is the creation of sets for theater productions. People can learn to do such work at the highly regarded College-Conservatory of Music, University of Cincinnati, under the direction of Thomas C. Umfrid, who is himself a highly regarded set designer.

Umfrid’s dual career as both teacher and maker, each aspect of which can fuel the other, seems to have evolved as a result of his pursuing his own interests in both. Now in his sixties, Umfrid is Professor and Resident Scenic Designer at the College-Conservatory and has been associated with the school since 1987; he has also played important roles at the Utah Shakespeare Festival and the Hong Kong Academy for Performing Arts and currently has ties to Beijing and Shanghai. The Conservatory, he says, expects staff to have both teaching and outside professional life.

He himself shrugs off the idea of himself as an artist. “Not trained to be one,” he says. He deals with a script, a song (someone else’s ideas?) and thinks about how the stage space will be used. His work “must support the director’s vision” and be part of a collaborative relationship with others, responding to many elements. Set and costumes must work together. He does say he wants to create something – “I’m not a decorator” – but adds that colleagues are vital. He wants to work with people who can interpret ideas. “Problems are the fun of it,” he says. “They’re only problems if you call them that.” Aside from a mid-’80’s try at New York City (not economic to be there, he explains) his professional life has played out in other parts of the country and the world.

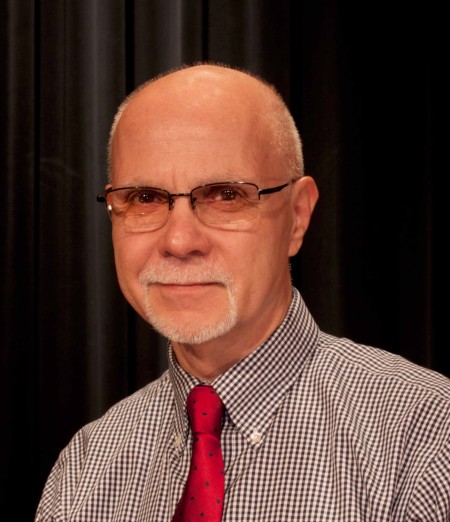

Umfrid has short white hair, short white mustache and brief beard, brown eyes behind rimless glasses. His surname is German, from the Black Forest area, but the family came to this country in the 19th century. Growing up in southern California, he received his undergraduate degree from the University of Southern California, going on to Minnesota for graduate school. In hindsight, Umfrid advises time between graduate and undergraduate studies. “At Minneapolis I learned how much I didn’t know.” He had not originally planned to teach, but “The Conservatory is not like a regular university. We’re not teaching theory, here it’s hands-on. . .all these hands touch.” Although faculty and students are more like colleagues than they would be in a more conventional school, he says that class room time and exams also have their place.

Asked what’s on the show schedule now and what’s coming up, Umfrid replies that the rock opera “American Idiot” has just closed “and was quite successful.” For fall he’s already planning set and props for “Cendrillon,” the late 19th century opera by Jules Massenet, based on the Cinderella story.

We talk in Umfrid’s office at CCM, in the lower levels of the building, windowless, a smallish room so jammed with objects that at first glance one wonders how anyone would find anything. An order to the place is quickly apparent, however. Umfrid seats us in a space that could accommodate several people for a small meeting and speaks of some of the myriad scale model set boxes tucked in rows up to the ceiling. Later, we move into the computer section of the office, look at tiny scale model computer-produced objects that allow the set boxes to foreshadow what will be on stage, and talk about what the computer has meant to the way he works.

“The T-square has given way to digital,” a circumstance he appears wholly satisfied with. “Digital is easier than drawing, and I can send things anywhere.” In the mid-1990s a sabbatical allowed him to concentrate on study of digital developments. He was not always quick, he says disparagingly, but “had a learning moment” that gave him the skills “to figure it out.”

As young man getting started in the business, Umfrid worked as “prop creative staff” at both the Santa Fe Opera and the prestigious Guthrie theater in Minneapolis – “excellent young emerging professional gigs,” he says. He moved into his eventual sphere at the New Mexico Repertory Theater, Utah’s Shakespearean Festival (twelve productions there) and other far flung stages as well as Cincinnati Opera, Playhouse in the Park, and Cincinnati Ballet here at home. He and his partner, “now my husband,” have been together for thirty-six years. “He’s a landscape architect. We understand each other’s language.”

Our interview ended, Umfrid led me down corridors, through doors, up steps, past elevators to the CCM garage, a path only a regular inhabitant of that space could have followed. Umfrid is clearly at home in his environment, and in addition “I love what I do,” he says. “CCM is a good place.” The definition of artist is flexible, and one element sometimes is loving what one does.

–Jane Durrell