Radical without a Cause: “Matisse: A Life in Color”

at the Indianapolis Museum of Art

By Keith Banner

A docent was giving a tour of “Matisse: A Life in Color” at the Indianapolis Museum of Art when I was strolling through. I overheard her say, “Matisse didn’t have any social causes in his work. He didn’t want his art to be weighted down with those kinds of messages. He wanted to please people with his art.” I wanted to add that he mostly was just trying to please himself. That wouldn’t be a putdown or slight either. As you witness the show (mainly made up of works from the Cone Sisters Collection at the Baltimore Museum of Art), up through January 12, 2014, you begin to understand that Matisse’s self-involved playfulness is what created the grandeur and momentum of his work. His world, like the writer Vladimir Nabokov’s, is a hermetically sealed universe of constantly reused signs and symbols, and his life work was the constant and feverish rearranging of all these colors and iconographies in order to find the perfect picture, encapsulating everything he was trying to do in one gorgeous, harmonious snapshot.

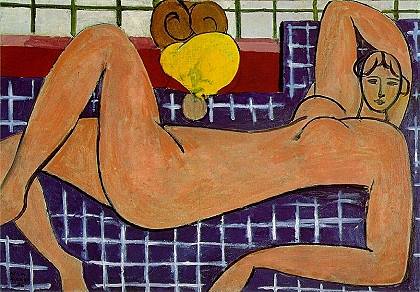

One of the first pictures to truly get at this great self-driven amalgamation is “Large Reclining Nude” from 1935, which is the centerpiece of “Life in Color.” It holds a wall like no other small painting can. Vigorously colored, and painted with a sort of secondhand dreaminess, “Pink Nude,” as it is also called, has a self-assurance and muscular whimsy to it; it seems to be contemplating Andy Warhol and Jasper John works that would be coming 25 or so years later, clean, quick, staring-straight-ahead pictures that have a Pop yet classical essence to them. The nude in the picture stares straight at you like Warhol’s Liz Taylor, but the surrounding paint job has that singular this-is-nothing-but-a-painting brashness that is letting everyone out there know the artist is not interested in verisimilitude. He’s trying very hard to find a picture worth painting.

In fact, next to “Pink Nude” in the show is a series of photos Matisse himself took charting the evolution of the work. It’s truly a mindblower, watching a glum, mediocre kind of realist painting slowly morph day after day into a picture worthy of worship. First the face goes, globbed into multiple shapes and masks, only to end up as the final product, a sort of mythic goddess merged with a dime-store crush. The body as well gets mythologized, moving from shape to line and back again. Matisse is flattening the surfaces but increasing the tension between foreground and background, object and subject so that by the time he finishes the metamorphosis “Pink Nude” is more like a poem than a photograph. He blurs the lines between what we think is “there” and what’s inside his head.

You can see this process as well in some earlier pictures from the 1920s across the way from “Pink Nude,” especially in 1922’s “Festival of Flowers,” an oil painting that looks as if Matisse hardly used any paint. Dry and wispy, the painting is made up of lines used to form shapes disintegrating toward the edge of the canvas. It’s a pretty run-of-the-mill set-piece featuring his daughter and her friend watching a parade pass by from the balcony of a hotel room, but the subject matter isn’t really what Matisse wants to capture here. It’s the essence of a memory of that moment, predicated on the desire of not losing it but not keeping it either. He’s elegizing with oils, turning the medium into the message, and the effervescent sloppiness of his style allows you to leave the real and start thinking about the aesthetic, maybe even the spiritual. That’s Matisse’s gift to all contemporary artists, that slapdash, blissful sense of insouciance given serious thought and practice.

Matisse’s very particularized genius is about taking what is conventional and staid and reinvigorating it through pulling it apart, running it through an aesthetic gauntlet inside his head, and creating pictures that are radical without really losing their sense of grace and even nostalgia for the predictable. His cause, if we were to posit one for him, was about a constant search for joy in the process of making art. While that sounds a little too whimsical and little too pompous, it’s right there in front of you in the works themselves in “Life in Color.”

The curators of the show validate Matisse’s trip to bountiful by finishing with Jazz, his famous artist book made up of paper-cuts from 1947. By this time, Matisse was suffering from poor health, and was at times bedridden. He took to using scissors as a way of making art so he wouldn’t have to stand in front of a canvas, and this pragmatic solution truly allowed Matisse to continue the burning away of what he didn’t need in favor of capturing an exuberant form of home-made purity. The collages in Jazz are simply breathtaking not because they are the works of a master, but because a master mapped a way out of his own canonization and physical decline by mapping a way in. The starburst and Tahitian-frond shapes that haunt the collages have a crisp elegance without losing a sense of play, an innocence that’s both effortless yet somehow constantly reconsidered.

Every image and shape in the Jazz portfolio has that sense of connectedness without losing a sense of disconnection, even disassociation, the scissor-work providing a sort of keyhole into yet another Matisse mansion. This last reinvention, however, was also a coda for a lifetime of experiments, a lifetime of quiet radical readjustments that created a body of work so immense and pleasurable one show can’t really capture the grandeur.

“Life in Color” does catch lightning in a bottle through by simply focusing our attention on the spectacular pieces the Baltimore Museum of Art acquired. The curators align, organize and embellish at every turn. If you go, definitely get the audio-guide. There are also explanatory I-Pads stationed throughout, as well as videos and well-written wall–text. If not an exhaustive retrospective, “Life in Color” is a paean to Matisse’s diligence and imaginative fortitude. The curators seem truly fond of his stubbornness to find perfection in whatever media he was using. In one of the accompanying videos in that last room of Jazz collages, an elderly Matisse cuts colored paper at a table, looking like a kid in a candy-store. That image is sentimental, but also transcendent, even symbolic. The last form of art-making he did was cutting away what he didn’t need: he found a form of total joy through excising the past.

Yes, god forbid anyone should have any fun with this stuff. It should be as fun to do as it is to look at. Yay, Matisse!!!

Yes, god forbid anyone should have any fun with this stuff. It should be as fun to do as it is to look at. Yay, Matisse!!!

Great taste of the show I will be seeing soon. Let’s also add that the great “Radical Intervention” show of Matisse at the Art Institute of Chgo showed his response to war and to Picasso/Cubism/Modernism. That show was brilliant and then, after Chgo, traveled to NYC. Shows them the Midwest knows what it is doing.So, tho Matisse was seen as ‘playful’ to use the reviewer’s words, he was really more than that.

Great taste of the show I will be seeing soon. Let’s also add that the great “Radical Intervention” show of Matisse at the Art Institute of Chgo showed his response to war and to Picasso/Cubism/Modernism. That show was brilliant and then, after Chgo, traveled to NYC. Shows them the Midwest knows what it is doing.So, tho Matisse was seen as ‘playful’ to use the reviewer’s words, he was really more than that.