This winter, three major New York institutions hosted exhibitions of immersive, moving image installations. In many ways the works featured in these shows were direct descendants of “expanded cinema,” a term now used broadly to describe many artistic practices engaging the physical situation of moving images outside of theaters though first applied to the utopian vision of artists using immersive cinematic spectacle for transformative art experience. Julian Rosefeldt’s multiscreen ode to modernism, Manifesto (2015), in the massive drill hall of Park Avenue Armory; a mid-career retrospective of Swiss video artist Pipilotti Rist’s immersive installations on three floors of the New Museum; and the Whitney Museum’s historical exhibition Dreamlands: Immersive Cinema and Art, 1905-2016 on its massive 18,000 square foot fifth floor galleries can all trace genealogies originating in many traditions of expanded cinema. In each of these shows, visitors moved from screen to screen in exploratory paths, shifting in and out of visual and diegetic immersion.

Manifesto explored the utopian hopes and anti-establishment spirit of twentieth century modernism. The work is simultaneously an homage to these great writers of the past and a comical pastiche of their tendency towards self-aggrandizement and hyperbole. Unlike the multi-room gallery installation of its previous showings, the Armory installed the work’s thirteen screens in one space in an arrangement that mimicked the Stations of the Cross. Going on the last weekend, I moved together among packed crowds of art world faithful from moment to moment of what were once modernism’s rallying cries but what are now the passionate death throes of the previous century. Following an antechamber screen of a burning fuse, the viewer navigates twelve vignettes starring Cate Blanchett in stunningly versatile performances. She delivers the words of F.T. Marinetti, Andre Breton, Jim Jarmusch, Claes Oldenburg, Sol LeWitt, Guy Debord, and others through very particularly twenty-first century characters and settings with varying degrees of comedy, emotion, and ambivalence.

On one screen, sweeping aerial shots move over the post-apocalyptic landscape of Teufelsberg, a hill made of the rubble of Hitler’s megalomaniacal architecture in Berlin. The camera finally settles on a ranting Scottish homeless man (Blanchett) delivering the manifestos of Situationism, a cultural movement sensitive to the ways built environment is an instrument of power. On another screen, a conservative Texas family sits in a meticulously decorated dining room as a bespeckled mother recites Claes Oldenburg’s repetitive “I am for an Art…” like a boring grace before the meal. In one of the most prescient screens, Blanchett plays a stock broker in a sea of computer screens. She utters the words of Futurist obsession with speed through a bridge-and-tunnel accent and smacks of gum, making a clear connection between the industrialist sentiment uttered by the eventually Fascist-leaning Marinetti and the acceleration of capitalism in speculative markets. Others, like the posh CEO politely toasting to the worlds of Wassily Kandinsky, Barnett Newman, and Wyndham Lewis, were less memorable. The cycle “ends” (if one took the clockwise, Stations of the Cross route between screens, as many did) with Blanchett in her native Australian accent teaching the principles of avant-garde filmmaking to a class of eager schoolchildren.

The setting, character, and text of each screen are linked thematically, but are decidedly anachronistic in terms of setting and jarringly disjunctive in terms of gender. Of the fifty-four texts cited in Manifesto, a whopping four were written by women. Delivered by Blanchett in such diverse contexts, the phony self-importance of these texts is laid bare and modernism is rendered a performative rather than sincere act. Though made of artifice and seemingly interchangeable, Rosefeldt and Blanchett’s modernism-as-performance is not an entirely hollow one, and certainly, as her passionate performances demonstrate, not devoid of affect. Towards the end of each eleven-minute cycle, Blanchett’s face is centered in a close-up and her delivery becomes monotonous, almost possessed. These moments connect the screens through a refrain that echoes throughout the hall, bringing together the many disparate (and at times conflicting) passions and movements. These moments turn the source texts into somnambulist chatter echoing throughout the hall.

Unlike Manifesto, a singular work on multiple screens, the New Museum’s exhibition Pixel Forest featured three decades of video and installation by Pipilotti Rist, whose work is simultaneously sumptuous, intimate, and overflowing with color and natural imagery. While the installation of Manifesto had a fairly regular promenade from screen to screen, Pixel Forest was far more exploratory, prompting visitors to spend as much or as little time with pieces of varying levels of immersion. Rist’s early work, such Ever is Over All (1997), a two channel corner projection featuring a woman gleefully smashing car windows with an enormous flower in slow motion (yes, that’s where Beyonce got the idea) melds into the artist’s more recent projections on delicate and swaying scrims. Rist’s early single-channel video projects were displayed as individual triangular viewing pods, mimicking the erotic corporeality and uneasy singular viewing of the pornographic peep show arcade. This feeling is amplified by the decidedly bodily content of many of these early videos, like the graphic birth in When My Mother’s Brother Was Born It Smelled Like Wild Pear Blossom in Front of the Burnt Brown Sill (1992) or the camera’s tactile exploration of the body in Pimpel Porno (1992). Echoing the awkwardness of the peep show installation, many of Rist’s installations more explicitly played with gaze and domination. Projected on the floor, Mother Floor (1996) looped two handheld shots from above Rist’s body, forming a Mobius strip entering her mouth and leaving her rear end. Our position above the image paralleled the camera’s position above Rist, much like the artist’s pleas to a bird’s eye camera in the small scale work Selfless in a Bath of Lava (1994), delightfully updated at the New Museum as a dropped iPhone in a stairwell.

On the next floor, the retrospective’s titular new piece Pixel Forest (2016) transformed half the floor into a dense web of fluctuating colorful lights. This installation was flooded with visitors even right after opening on a Thursday. Recently written up as one of the top places to grab some Instagram selfies, visitors were glued not to Rist’s screens but to their own as they fashioned their new profile pictures inside the forest of light. Also on this floor where the large scale corner-projected pieces Mercy Garden and Worry Will Vanish Horizon (both 2014) complete with plush bean bags for relaxed, immersive viewing. Finally on the top floor, Rist debuted another new work, 4th Floor to Mildness (2016), featuring a singular and immersive soundscape, two large ceiling video projections on cloud-like forms, and scattered floor projections across a gallery covered with beds. The dreamy underwater images and music transformed the space and prompted the audience to lie down, literalizing the connections between cinematic immersion and sleep all the while calling attention to our body’s transgression of the normative behaviors of the museum.

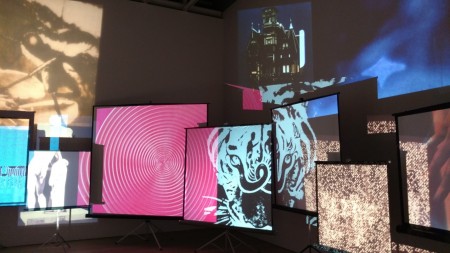

At the Whitney, Dreamlands also asked viewers to contemplate the connections between dreaming and cinematic immersion, but offered a much more scattered, though historically comprehensive, viewing experience. Spanning from early silent film to the latest work by emerging artists, the exhibition included such iconic figures in expanded cinema as Anthony McCall, Stan Vanderbeek, and Oskar Rischinger. As Erika Balsom notes in her review in Artforum, the exhibition’s breadth lead to somewhat tenuous connections between the many different explorations of the moving image in over a century of art. Unlike how the screens rang a chorus in Manifesto or the coherent intermingling of immersive spaces in Pipilotti Rist’s retrospective, the shifts between works in Dreamlands left the viewer feeling disoriented. The recurring presence of versions of Annlee, a background anime character bought by Philippe Parreno and Pierre Huyghe and “liberated” in works by them and many other contemporary artists, attempted to form a connection between spaces, but the complexities of this collaborative project were muffled among the many different viewing experiences.

Nevertheless, many works were still singular and transfixing viewing and welcome surprises in the crowded exhibition. Anthony McCall’s Line Describing a Cone (1973), also a fixture of the Whitney’s 2001 exhibition Into the Light: the Projected Image in American Art, 1964-1977 (one of the first major museum exhibitions to historically exhibit this type of work), transforms the projected image into a sculptural installation and immaterial cone of light. Lynn Hershman Leeson’s Room of One’s Own (1990) made for uniquely uncomfortable voyeuristic viewing. As I peered through the peepshow-like opening I moved the apparatus to face different points in a small diorama to reveal a woman in a bedroom in various stages of undress, despair, and confrontation. Her voice—piped loudly into the gallery space— repeatedly admonished me for watching her and asked me to look away. Only when looking at the live image of my own eye on a tiny screen did the attack on my gaze stop, a sharp critique of the cinema viewer’s anonymous consumption of the woman’s body.

The most memorable work in the exhibition, though perhaps the most traditionally cinematic installation, was German artist Hito Steyerl’s Factory of the Sun (2015). Like most of the artist’s films and essays, Factory of the Sun explored the interconnections of digital images, immaterial labor, and state and corporate sponsored violence. Shot like a video game complete with on-screen stats, tutorial stages, and the ability to respawn, this film imagines a world where forced laborers dance in a motion capture studio to produce artificial sunlight. Steyerl exhibits her film in an enclosed theater mimicking the gridded spaces of a motion capture studio, placing us in the interstices of the material and immaterial movement. The infectious dance soundtrack, humorous asides and on-screen text, and dense imagery and narrative require multiple viewing. In one scene, laborers dance in gold spandex suits atop the former NSA listening towers in Teufelsberg, Berlin, the same modernist ruin featured in Manifesto uptown. Like Rosefeldt’s multiscreen film, Steyerl’s work here explores the limitations and contradictions of utopian thinking. Only Steyerl is less concerned with modernist aspirations and more interested in critiquing the exposing the material violence of the digital age. The film constantly pulls in and out of its production (Steyerl even appears as the director a few times, though she is also dressed in the gold spandex of the dancers), destabilizing what is film and what is the making-of.

Like the hollow modernist mantras in Manifesto or the simultaneously dreamy and corporeal landscapes of Rist’s Pixel World, expanded cinema places us at the nexus of the physical and the immaterial and asks us to explore both spaces simultaneously. Though these three exhibitions had varying levels of conceptual clarity and cohesion, their scale and successes signal the establishment acceptance of expanded cinema and its more contemporary descendants. However, these installations’ many prompts to explore and unravel the ways in which fiction, fact, illusion, and reality comingle seems particularly apt to our present cultural moment.

—Annie Dell’Aria