An undercurrent of pleasure runs through the exhibition Biophilia, Standing Witness on view now through October 20 at Studio San Giuseppe Art Gallery, Mount St. Joseph University. Twelve women artists, all with roots in Cincinnati and/or Columbus, are each represented in some depth – not easy in a show including so many artists.

The exhibition is designed to honor Sister Paula Gonzalez, SC, who influenced each of these artists in recognizing and celebrating human relationship to the natural world. Sister Paula died in August, 2016, but is alive in the memory of the artists shown here. The theme for the exhibition is a quotation from Sister Paula: “The most striking realization we had was that everything – humans and non-humans alike – is connected and interdependent.”

Biophilia, Standing Witness centers on that relationship, exploring possibilities offered by a line of thought that both examines and illuminates the natural world. People, it should be said, appear not at all in these works, which range from paintings and prints to sculptural objects and never loose their steam. The artists who produced them are comfortable in withdrawing to let the natural world take center spot.

Biophilia, a word new enough that my computer itself doesn’t recognize it, refers to “the innate affinity of human beings with the natural world,” I learned on-line at a reputable site. The exhibition suggests in itself the welcome indication that human relationships can flourish within a nature-oriented outlook. Its contributing artists are clearly pleased to be “standing witnesses” to that fact, but each responds with her individual approach to the exhibition’s central concern.

Many of the works here are small, which makes it possible to have a generous showing from each artist in the modestly sized gallery at Studio San Guiseppe. The corridor extending the central space lends itself handily to smaller works but also includes a splendid hanging piece which isn’t small at all – it’s roughly the size of a bed spread – by Judy Dominic, whose posted statement says she uses “what’s available” and “no scissors” to make her art. In this case what’s available includes silk scarves, cotton embroidery, beeswax, muslin and more, made into handsome hanging strips, browns and orange on white predominating. Elsewhere, she plays with the idea of bird nests and presents two of them, titled “Ledge Housing.”

Several small ceramic pieces that look as though they could perhaps come from the sea, by Brenda Tarbell, are also among the works shown along the corridor and in another location her “Three Succulent Forms” presents a different take. The Forms are ceramic, yellow and brown, rounded, each creased, in three different sizes that could pass for footstools if they didn’t have such a sense of life. They are shown as a unit.

A very different approach comes from Heather Wetzel, who turns to a historic photo process and transfers abstract drawings onto metal discs that originally were lids to cans, assembling a considerable number of them into wall hangings. Each disc is individual and rewards close looks.

Pam Korte, co-curator of the exhibition, notes in her statement that she has “been in the looking business for over forty years,” a nice reflection of the importance of the way an artist sees the world he or she is reflecting in art. She calls her work “a translation” of what she sees, and is represented here by delicate porcelain pieces with thin, curled lips. Velma Dailey, director of Studio San Giuseppe, is her co-curator for the show.

Margaret Rhein’s hand-made papers are endlessly inventive and appear here in intricate paper collages that include found objects, natural pieces and the occasional quotation from literature. She likes to record who gave her certain interesting portions (“cut-out butterflies gifted to me by Gail Lehing” is one note) and has assembled a number of appropriate elements for the piece titled “Wanted: Woman Attractive to Butterflies.” Butterflies, it’s clear, are attractive to Rhein.

Lisa Huell Conner’s porcelain pieces show imaginative handling of familiar shapes (a bowl, a plate) but she has another side as well. “Cincinnati Monolith,” a column perhaps five feet tall purporting to have small fossils along its surface, is a different take. A pair of pieces made of stoneware and Brookline red clay are titled “Ammonite Recalled,” reminding of the history that unobtrusively surrounds us.

Other works echo this suggestion of long memory and evolving characteristics: Kristen Swanson Bowen’s enigmatic oil painting of a songbird has light colors high in the composition and thicker, darker paint on the lower portions with the implication of change. Sandra Jane Heard has built two small sculptures incorporating reeds, silk and linen, metal bars, the letters from an old fashioned typewriter and for each a round mirror five or six inches across, so that the viewer becomes part of it. One is called “The Remembrance Device;” the other “The Spiteful Summer.”

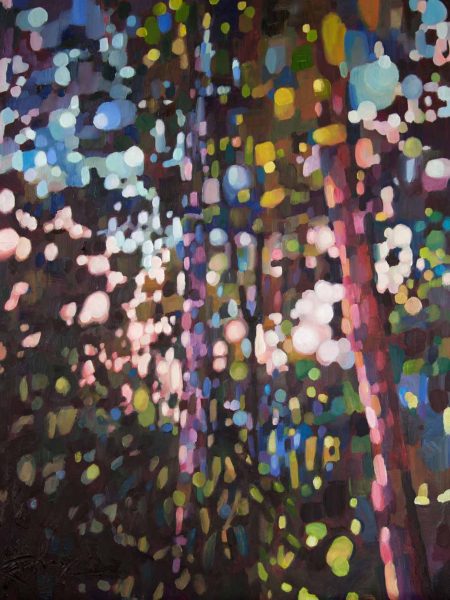

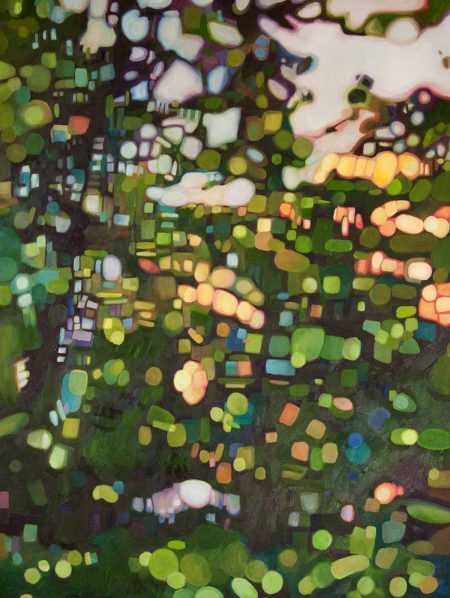

Terrie Kern has said her small, detailed ceramics are “visual markers” that commemorate particular memories. They are unspecific enough to be evocative of memories for others as well. Renee Harris is seriously caught into small forms of life – frog, fish, spider, flowers – and presents them as nature alive and well, portrayed by graphite pencil and acrylic paint in appealing colors. Another painter, Karen Rumora, throws things out of focus in the example seen here, so that light and color rather than object is the subject. Leah Stahl’s black and white prints, functioning as abstracts, are square shaped and invite close attention.

Most of these artists, perhaps all, have been making art for a long time and those I’m familiar with have evolved with the years. The exhibition not only explores “nature/earth/life . . .and the interconnectedness to nature and spirituality” as the exhibition announcement states, but also suggests a serious and effective art community.