“Capriccio,” Michael Dopp’s show in Roberts & Tilton’s small secondary gallery, features 18 ink drawings brimming with symbolism. From afar, their washy Old Masterish monochromaticity suggests pictures one would find hanging in a musty museum or library display case rather than on the walls of a contemporary gallery. Closer observation reveals that the venerable academic semblance belies impishly fanciful compositions. Most depict classical architectural or statuary ruins inside globular vessels resembling cocktail glasses, fishbowls, or snow globes. Underlying the drawings’ cartoonish appearance are sober reflections on timeless binaries: of the anxiety and cavalierism with which civilizations view their own caducity; of the veneration yet commodification with which cultures view their predecessors.

Fascination with ruins transcends era and location and pervades the histories of arts and cultures high and low, from ancient times to modern. One need only look at Brian Dillon’s 2012 essay, “Ruin Lust: Our Love Affair With Decaying Buildings” for a history and bibliography–and that’s only one article.1 Dillon also helped curate “Ruin Lust,” a 2014 exhibition at Tate Britain chronicling artistic depictions of ruins from the seventeenth century to present.2 Simply put, “ruin lust” is a cliché. Dopp’s work embodies the cliché to highlight its significance as a cultural phenomenon both ancient and recent.

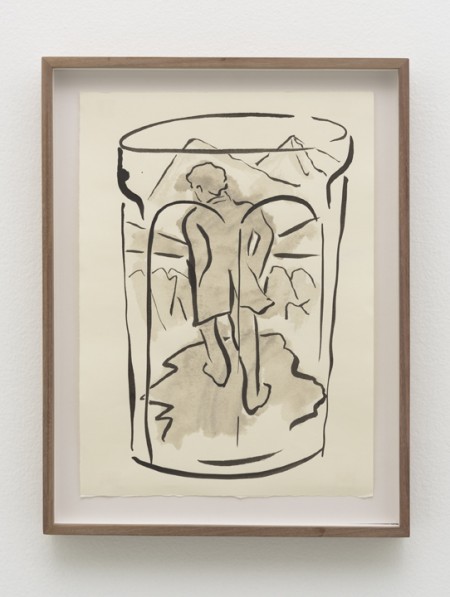

Ruin lust was integral to longstanding traditions of the European “Grand Tour” and the capriccio.3 Dopp’s drawings affect having been torn out of the Grand Tour sketchbook of an artist or architect who stopped at a bar and imbibed a glass of wine while sketching ruins he had seen earlier in the day. His simple, imaginative looseness evokes the sorts of reveries that might be induced by a traveler’s wonder, fatigue, alcohol, and boredom. Dominoes in Capriccio_5 (all works 2016), and Capriccio_16 symbolize civilizations’ downfall as much as they suggest games played in leisure time.

As Bruce Redford postulates in Venice and the Grand Tour (1996), “Indeed, one might go so far as to say that travel abroad existed for the sake of ostentation at home, the Tour supplying the most effective props of all for what E. P. Thompson has called a ‘theatre of greatness’.” Flaunting one’s worldliness by way of souvenirs was as customary then as today. Dopp’s drawings not only suggest sketches as mementos, they also seem like sketches of mementos. Dwarfed by dominoes, small enough to fit in drinking glasses, delineated generically in broad strokes, these depicted ruins look more like miniaturized souvenir facsimiles than actual architecture.

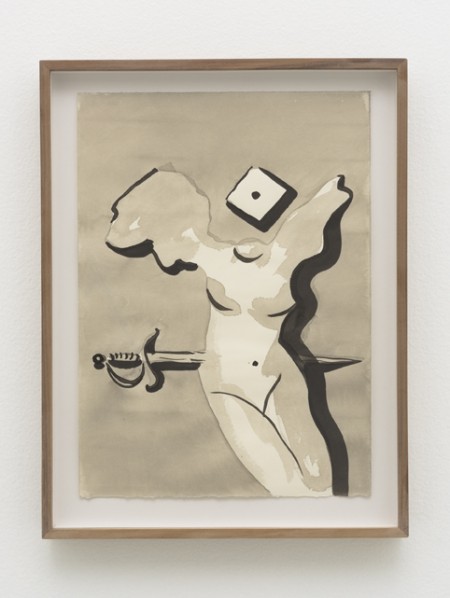

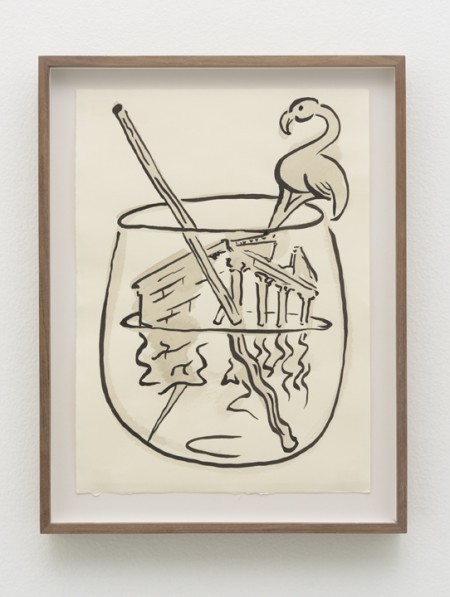

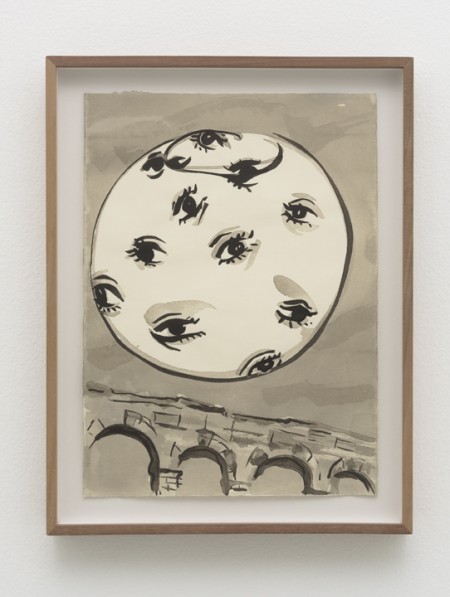

Indications of trinket-hood are multi-layered. Sabers act as swizzle sticks and impale a headless, armless Nike, referencing the ways in which instruments of violence become honored symbols of civilizations’ greatness later to be recycled into tinsel of historic pastiche. Notions of the sublime are reduced to burlesque in works like Capriccio_14, where a water glass encapsulates a composition roughly resembling the focal point of Caspar David Friedrich’s Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog. Outrageously whimsical touches like eyes in a bubble in Capriccio_12 evoke Salvador Dali, Tony Oursler, and New Yorker cartoons. In Capriccio_7, a flamingo-shaped swizzle stick betokens total convolution of location and scale. Are these replicas mementos from European trips, or merely cheap tchotchkes from simulations like the Las Vegas Venetian or Paris? Or were the ruins wistfully copied from some cruise brochure? Either way, these visions of the past are decidedly contemporary.

Our current time is rife with apprehensiveness about the future of our civilization and the rest of the world. Mass exoduses from cities like Detroit leave in their wakes ghost towns of deserted buildings.4 ISIS destroys ancient sites including Palmyra. It is said that oceans are rising, soon to engulf large swaths of land. Dopp’s pictures play on these anxieties. Straws, such as the black tube penetrating a window in Capriccio_18 appear probing and sinister, as though about to vacuum or bludgeon whatever life the edifices still harbor. It’s impossible to view the liquid inundating the buildings in his drawings without thinking of natural disasters, swelling seas, financial crises, climate change.

Vessels hover above bucolic landscapes, looming and distended like bubbles about to burst. For all our latent fears of the possible devastation of our own civilization, perhaps as a result of them, we view the derelict remains of predecessors with a nostalgia bordering on the idyllic. It’s as though it couldn’t happen to us, as though devastation were a mere myth, an abstraction of yesteryear. Or more circumspectly, we take comfort in the fact vestiges still remain. There is beauty in the ravaged. The neatly bottled fluid in Dopp’s glasses brings to mind shipwreck fantasies, the lost city of Atlantis. We contain fears of our devastation inside the surrogate vessels of our predecessors, ignoring our society’s dangerous actions.

Yet despite these dismal connotations, the containment of the liquid also bespeaks less gloomy notions. Water globes are diverting baubles. Fish tanks are decorative, meant to be observed. Drinks are to be relished. In part, the same is true of art. Though apocalyptic, these drawings are amusing.

The staggered refracted boundaries of straws in works like Capriccio_8 symbolize parallel but divergent visions of the same object. Ruins captivate us; and we are possessive of them. They thread us to bygone ages. From disintegrated buildings we create National Monuments and restorative imitations. How entertaining these can be, like theme park replicas. Much is to be learned from observing deteriorated architecture, but how was it in its heyday? How much do we project upon them? Dopp’s capriccios capture such ambiguity and ambivalence.

Beholding ruins depresses some and obsesses others. Some act hilariously at demolitions of historic buildings, others mourn over them. His combinations of whimsical and pedantic, humorous and lugubrious, mirror the opposing sentiments with which societies reflect upon themselves.

Michael Dopp’s “Capriccio” is on view January 14-February 18, 2017 at Roberts & Tilton, 5801 Washington Blvd., Culver City, CA 90232.

–Annabel Osberg

1 https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2012/feb/17/ruins-love-affair-decayed-buildings

2 http://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-britain/exhibition/ruin-lust

3 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Capriccio_(art)

4 See my article, “Painted City: Looking at Art on the Streets of Detroit,” published 4/07/14, The Huffington Post: https://web.archive.org/web/20151015055011/http://www.huffingtonpost.com/annabel-osberg/detroit-street-art-graffiti_b_5093406.html