This article is the second of a two-part series about shippers, framers, conservators and preparers in the Greater Cincinnati area.

Look no further than 1309 Vine St. where Suder’s Art Store has served the community for years. Sharon Suder, now managing the store, traces its history to 1924 when her husband’s grandfather John Suder Sr. opened the business at 1301 Vine St. It moved up the street in 1931. John, Jr., and Herman Moeller operated the store until Sharon’s husband David, John Jr.’s son, took over and bought out Moeller. David is technically the proprietor though he doesn’t work here. He works at his other business, Suder Engine Service.

“Probably our largest challenge is competing with the large internet stores,” said Suder. “We try to make our store attractive by offering the best service we can and keeping a wide range of art materials. We also have artists’ services like building custom supports, canvas stretching and shrink wrapping.”

Suder counts the framing and restoration services as its largest sellers. The store has custom framing and ready-made frames. Suder’s sells glass, framing hardware, matting and length molding. Restoration services include cleaning, repairing damaged paintings, restoring and rebuilding old frames, gilding and custom finishing.

Suder’s stocks a wide variety of art materials. Paper, pastels, chalks, conte pencils and crayons, graphite in all forms, charcoal, sculpting items, canvas stretchers, easels, palettes, sprays, printmaking supplies and more form part of the complete inventory.

“One thing that is unique to us is the age of the business,” said Suder. “When you come in the door, the building is permeated with the smell of art supplies that has built up over the decades. And the service is personal and knowledgeable,” she said. “We try to gear our inventory to people’s needs.”

Suder notes that the industry is always in flux. Companies are bought and sold. Some supplies disappear and new ones come on the market. Technology is ever changing the field. But people will always need to create, according to Suder, who is grateful for an arts community that has supported the store for 93 years.

This story wouldn’t be complete without talking to Serena Urry, chief conservator at the Cincinnati Art Museum. A member of the CAM staff for the past four years, Urry accepted a promotion from a position as senior conservator of painting at the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia. Now, she manages not only three people, but also an encyclopedic collection of 67,000 pieces. Of that number, approximately 45 – 48,000 works are on paper.

A highlight of her CAM career is Conservation of View: Zaragoza’s Retablo of Saint Peter, which ran from January 26 to April 24, 2016. Urry was on view four to five hours cleaning the Retablo. The Spanish altarpiece, attributed to Lorenzo Zaragoza, dates to around 1400. Its 18 painted panels show scenes from the life of Saint Peter on a rich, gilded background. Urry is continuing to work on the Retablo in the conservation room of the museum. She anticipates it may take several years to finish the project.

Another of Urry’s projects is doing minor cosmetic work on an early 19th century pair of portraits by John Brewster of Captain James Perkins and his wife Sarah, a recent gift to the museum from a private collection. They are part of the CAM exhibit A Shared Legacy: Folk Art in America offered from June 10 – September 3, 2017. The exhibit features more than 60 works of art created by self-taught or minimally trained artists between 1800 and 1925. Barbara Gordon, who lives outside Washington, D.C., accumulated the collection over the course of 27 years.

The current complex Dressed to Kill: Japanese Arms and Armor exhibit involved three CAM conservators who focused their attention on textile, objects and paper. Urry said this was unusual to have so many conservators involved.

Urry counts the benefits she has in working in a museum as opposed to a business where she has the luxury of time, for example, working on the Retablo. Another achievement she mentions is the establishment of a textile conservation lab, new to CAM, which opened in 2014.

The Cincinnati Art Museum established the Conservation Department in 1935, making it one of the oldest in America. It began with one part-time paintings conservator in 1935 and now has several professionally trained conservators on staff. In addition to Urry, these include Cecile Mear, conservator of works on paper; Kelly Schulze, assistant objects conservator and Chandra Linn, associate conservator of textiles.

Conservation is a profession dedicated to preserving cultural heritage, according to the CAM website. To work in this field requires special training, only available in four art conservation training programs in North America: Institute of Fine Arts, New York University; State University of New York, Buffalo; University of Delaware, Wilmington; and Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario. Each program accepts six to ten students a year and requires a two to four-year commitment with a background in art history, studio art or chemistry. Urry received an MA MS, a double degree with a master’s in art history and a diploma in conservation from NYU. Jobs in the field are readily available.

Urry found her inspiration in the field of conservation when floods ravaged Florence on November 4, 1966. The surge of muddy, oil-ridden water from the Arno River came rushing into the center of the city in the middle of the night, killing many people, devastating houses and shops, and damaging approximately 1,500 works of priceless art and manuscripts. The water knocked Lorenzo Ghiberti’s famous doors to the Baptistery flat in the mud, half ruining Giovanni Cimabue’s painted wood crucifix in the refectory of Santa Croce, and flooding approximately one million precious books and archival documents in the Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale Firenze. The crucifix became the symbol of tragedy and rebirth of Florence.

Roughly two-thirds of the damaged artworks were repaired in the first 15 years after 1966, but another 450, including Vasari’s Last Supper and Carlo Portelli’s Assumption with Saints languished untouched for lack of funds. Conservation took years.

According to Dr. Donal Cooper, university lecturer in Italian Renaissance art at Cambridge University, the flood drove change and innovation in the practice of conservation, e.g., saving frescoes without detaching them and preserving manuscripts using historic materials and techniques. The post-flood response stands as an example of international collaboration and laid the foundation for Italian excellence in art conservation.

Jill Dunne, CAM director of marketing and communications, said, “Conservation may be an art and science.” To plan a treatment involves more than meets the eye. Courses in a conservation program include chemistry and physics. Conservators look at a work of art with ultraviolet and infrared light, x-radiographs, microscopes, micro-chemical testing and micro-sampling.

The conservators then decide on a plan of action. A number of factors may influence the conservation of a piece. For example, room temperature, relative humidity, lighting, storage space, pest control, gallery layout, proper handling, packing and crating materials all play a part. In addition, historical research and collaboration with the curator aids the process.

Across the river is Bowman’s Framing, Inc., located on 103 N. Ft. Thomas Ave., Ft. Thomas, Kentucky. Ken Bowman inherited his grandfather J. Julian Bowman’s interest in the business because Julian owned Art Publishers in a warehouse on Gilbert Ave. from 1937 to 1988. In 1983 Julian drafted Ken to work for him. Ken left the world of Radio Shack management to build frames and sell molding. By 1993, Julian decided to retire and put everything up for sale.

With encouragement from friends, Ken opened Bowman’s Backdoor Framing, a reference to the location and entrance to the building. He worked in the basement of the Ft. Thomas house and bought the house in 1998. It took him two years to obtain a zoning change to make the move from the basement to the main floor. Bowman then renovated the space. “I am better able to function as a gallery in the house,” he said. “The basement shop was very limited in display space.”

Bowman said he worked like a dog to compete in the business. One large project was doing 120 frames for the former Cooker Bar & Grille with restaurants all over the midwest in places such as Florence and Beechmont, now closed. He said that thousands of frames are available to his customers who come from both sides of the river. “I couldn’t survive on just Ft. Thomas traffic,” he said. His customer database numbers 7,000 in the mid to upper income level. But, he said his rates are competitive. Bowman remains tied to Ft. Thomas and has served on Ft. Thomas City Council for five years.

His tag line used to be, “We have no one time customer,” as he reached out to all of his customers. Ken described some of his services, such as cross stitch framing, shadow box framing, custom mirrors, and framing of vintage posters from the Jack Wood Gallery in Cincinnati.

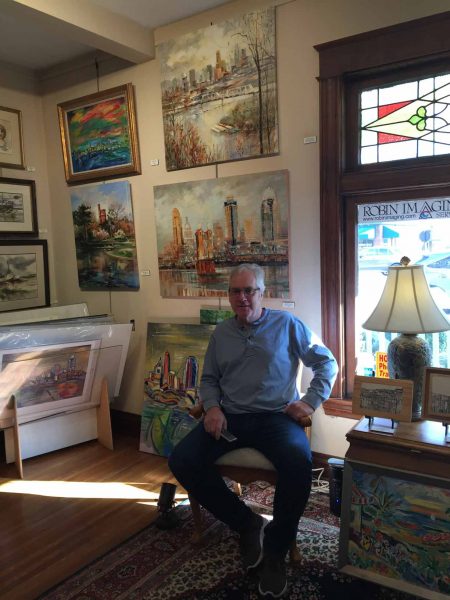

Bowman’s gallery also features artists such as Gina Stevenson, Ted Borman, Beverly Erschell, Deborah Morrissey McGoff, Ken Landon Buck and Sally and Jonathan Kamholtz. Not only does he work with experienced artists, he offers framing, minor restoration, consultation for Cincinnati’s Robin Imaging Services, one of the few photo labs still open, and onsite consultation with clients for installation and display.

He thinks what sets Bowman’s Framing apart from other shops is a sense of design and aesthetic skills gained over the years. Bowman believes he knows how to enhance a painting. “We’re doing things differently than in previous years,” said Ken. Yet, he acknowledged that his biggest weakness is marketing. He relies a lot on word of mouth. “I don’t go after it,” he added. Work comes to him.

Jayne Menke took on a daunting task: She bought the oldest art gallery in Cincinnati – Miller Gallery – in February 2015. She kept the name Miller Gallery after Norm and Barbara Miller who operated the fine art gallery since the 1960’s.

Her trek to owning Miller Gallery began earlier. Menke has a sales background although she has a BFA from Mt. St. Joseph University. She worked in pharmaceutical sales at Schering-Plough. At one point in her career, she said, “I wanted to do something more creative.”

She joined the Winn Art Group as an art consultant. Menke gained experience calling on corporations and making framing. A friend at Winegardner & Hammons, Inc. Hotel Group designed hotels. They were rolling out Marriotts in the city, and Menke was able to get the job of supplying art.

By 1994, she was ready to start on her own and opened Artonomy, which offers full service art consultation, design, custom production, shipping and installation. She began working out of her home which included a frame shop. She eventually bought a building at Fourth & Plum Streets

Menke has operated Artonomy for twenty years. She has many corporate and retail clients, such as GE Aviation, American Girl, UC Health, Hyatt Hotels and Hilton Garden Inns.

Menke has a sales background although she has a BFA from Mt. St. Joseph University, she worked in pharmaceutical sales at Schering-Plough. At one point in her career, she said, “I wanted to do something more creative.” She joined the Winn Art Group as an art consultant. Menke gained experience calling on corporations and making framing. A friend at Winegardner & Hammons, Inc. Hotel Group designed hotels. They were rolling out Marriotts in the city, and Menke was able to get the job of supplying art.

By 1994, she was ready to start on her own and opened Artonomy. She began working out of her home which included a frame shop. She eventually bought a building at Fourth & Plum Streets. One large order was for Hampton Inns where she provided art and mirrors.“The industry has changed,” said Menke. She felt the need to be more creative. Menke bought a warehouse at 544 W. Liberty Street. She now has 35 employees there and two at Miller Gallery. Lauren Johnston serves as director of creative marketing and Jen Gallat as director.

Recently, she received a contract to provide art at the Mandarin Oriental Hotel in Duha. It is a large order with 500 pieces of custom design work.

She met Gary Gleason, former co-owner of Miller Gallery, who indicated he was selling the business. He wanted someone with a strong business sense, which Menke now had. “I feel the responsibility to bring Cincinnati into what is happening in the rest of the world,” she said. Anyone who comes into the gallery notices the difference between the past and the present.