At the outset of the tumultuous 1960s, more than 25,000 Cincinnatians found themselves evicted from their homes by city planners. Those losses came as a result of the Kenyon Barr project, which the planners named after two major streets in the city’s Lower West End, and which promised to revitalize approximately 297 acres of largely residential land. Kenyon Barr focused on an area affiliated for over 100 years with Cincinnati’s famed pork-packing industry, a neighborhood that featured delis, hardware stores, loan offices, jewelry shops, churches, and synagogues amid an array of historic homes and apartments. It also included an extraordinary nightlife where African American and European cuisines intermingled while such luminaries as Duke Ellington and Dinah Washington gave concerts in local venues (Suess; Swartsell). However rich this history, it gave way to the Mill Creek Expressway and then I-75, as well as to small factories ranged along the rail yards in what would become Queensgate (Hurley). Fewer than 200 people now live in the zone that Kenyon Barr marked out for revitalization, and a dwindling number of citizens can recall the Lower West End before the demolition occurred.

As the 1950s came to an end, planning commission employees made a detailed photographic record of the buildings chosen for elimination. A selection of those pictures now hangs in the Philip M. Meyers, Jr. Memorial Gallery at the University of Cincinnati, along with fire insurance maps that show each structure’s location in the West End grid. Historian Anne Delano Steinert gathered those forty images from over 3,000 such documents that are housed at the Cincinnati Museum Center, calling the resulting exhibit Finding Kenyon Barr: Exploring Photographs of Cincinnati’s Lost Lower West End. The black-and-white photos spotlight eclectic structures in various states of repair, from magnificent spaces of worship to shotgun houses plainly in need of restoration. Most of the buildings huddled well within those poles, though the city determined that almost none of them were “up to code” (Swartsell). The pictures also include people at different stages of life going about their daily routines, reminding gallery-goers of whom the houses and shops served. The pictured subjects’ lives would be upended by 1960, with most people moving to Evanston, Avondale, and Walnut Hills (Hurley).

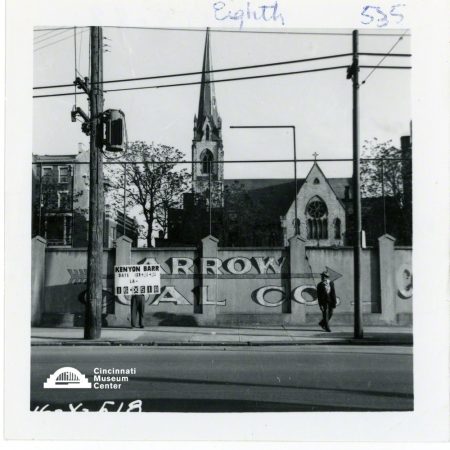

One of the more evocative images includes a house of worship guarded by a fence reading “Arrow Coal Company.” It mixes references to the sacred and the mundane while condensing the dynamics of communal life in accidental but profound ways. Telephone poles and electrical boxes stand as material markers of communication, of information and energy circulating among the district’s inhabitants, the place in dialogue with other places. Yet a figure interrupts the everyday quality of the scene by standing before the fence with a “Kenyon Barr” placard that itemizes the space by date and plot number. The placard is the whitest thing in the image and a portent of the scene’s imminent erasure.

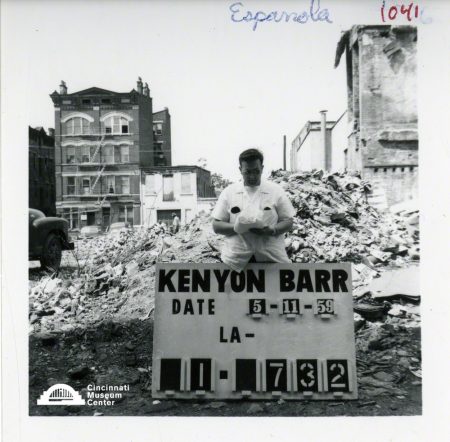

The presence of the placard momentarily indicates bureaucratic distance, but the curious gaze of a passerby disallows the pretense at neutrality. The Kenyon Barr signs appear in every photograph, sometimes finding echoes in the official city vehicles parked in front of the buildings. The citizens look on with confusion, distrust, anger, and resignation, sometimes all in the same picture, sometimes all in the same expression. Children continue to play while a cruel machinery operates around them, bringing changes they have no power to control. Then again, the adults in the community hold little more influence than the children, as city planners never asked for resident input. Even with the exhaustive accounting for the place in its final year, NAACP Executive Secretary Kenneth Banks noted that the city gathered limited statistics about lower West End occupants as it developed the Kenyon Barr plan, paying no attention to how many people it would displace (Swartsell).

The proleptic quality of the photographs gives them a grim suspense, yet the certainty of the place’s future turns that suspense to grief. In that way, they resonate with Roland Barthes’s meditations in Camera Lucida, where he contends that photographs are at least partly about temporality, with each shot prefiguring an inevitable aging and decay that it can neither hinder nor redress (14-15). The placards that inhabit the images strengthen the sense that a sentence has been passed, transforming the scenes into mug shots not of singular human suspects but rather of front stoops and alleys, sidewalks and doorways where lives once moved and intersected, even if their surroundings were not “up to code.”

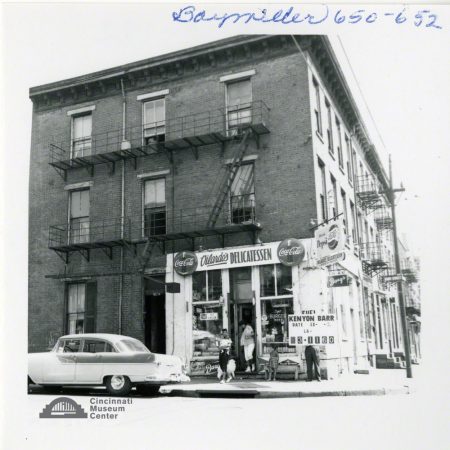

One of those doorways exists at Vilardo’s Delicatessen, where people hover at the threshold of the locally owned grocery, the indication of a local proprieter underwriting the ethos of neighbors serving neighbors. People and pets linger on the sidewalk, apartments and fire escapes lining the facade as the cola wars play out on billboards and benches. A baby nuzzles a woman as an older girl looks on. In an interview with Hillary Copsey, Melvin Grier tells of the sense of kinship that characterized the West End when he grew up there: “People looked out for others’ children,” he explains to her. “Kids played throughout the neighborhood. Neighbors took care of each other and helped out when folks were sick. They gossiped on stoops and shopped in the same neighborhood where they lived and worked.” The photo of Vilardo’s channels much of that liveliness, supporting Dan Hurley’s observation that the West End “was not only the primary residential neighborhood but a vital community with an infrastructure of family businesses, stores, schools, churches, entertainment venues and social agencies.” Hurley further observes that the area drew professionals from outside enclaves to address the specific needs of its population: “African American doctors and lawyers, even if they lived in Walnut Hills, usually had their offices in the West End.” Certain of its venues also had political significance as places where “African American leaders could talk frankly and be confident that what they said wouldn’t get back to white leaders” (Hurley). In that light, Kenyon Barr looks all the more like the imposition of white authority on a place that had, to that point, mostly eluded its hold.

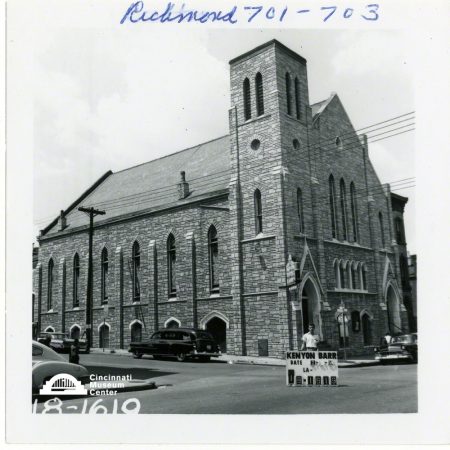

The project also dislocated a number of faith congregations, including the one at Richmond Street Christian Church. Historic for its outreach work, that church founded the Christian Woman’s Board of Missions while helping to establish “thirty congregations in Ohio, Oklahoma, Illinois, Arkansas, Virginia, Michigan, and Iowa” (Mason). The monumental structure, complete with bell tower and rows of stained glass windows, commands the attention as powerfully as anything in the exhibit, but it acquires an additionally sublime quality when juxtaposed with a photo taken on Espanola Street on May 11, 1959. In that image, a city employee checks his papers as a pile of brick and rubble rises behind him. “We were still living there when they were tearing buildings down,” Grier tells Nick Swartsell of Citybeat. Workers who took on the assignments of so-called slum clearance and urban renewal often went about their tasks with a calm detachment, eliminating churches as readily as apartments and groceries, showing little interest in the traditions they destroyed and similarly small concern for where the inhabitants would go next.

Those inhabitants carried the communal memories and the pain of loss with them for the next sixty years. Hurley suggests that resentment of the Kenyon Barr initiative helps explain Cincinnati’s participation in the nationwide uprisings that occurred almost a decade after the demolitions. The “long, hot summer of 1967” and the unrest after Martin Luther King, Jr.’s assassination arose in response to a history of city officials ignoring African American voices while doing violence to their bodies, cultures, economic prospects, and their neighborhoods (Curnutte; Kiesewetter). The memory of Kenyon Barr also helps explain the resistance to recent renewal projects such as the Futbol Club (FC) Cincinnati stadium, which is slated for West End completion in 2021 (Hurley; Hatch). Given the controversy over that issue, the exhibit comes at a fitting moment. The timing is testament to Steinert’s savvy curation, which elicits enormous sociohistorical significance and affective weight from a collection of bureaucratic texts. Those texts arose from a process of planning and preliminary engineering, but now they serve as a kind of forensic key, permitting an autopsy of the (un)built environment. The show extracts found art from the archival dig, deriving a piercing political aesthetic from the pose of having none. Sometimes the tacit argument of inevitability, of merely marking the path of progress, constitutes aggression in its most strategic and ruinous form.

–Christopher Carter

Works Cited

Barthes, Roland. Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography. Trans. Richard Howard. New York: Hill and Wang, 1981.

Copsey, Hillary. “‘Finding Kenyon Barr’ Photo Exhibit Brings Razed West End Community Back to Life.” WCPO Cincinnati, 13 Nov. 2017, www.wcpo.com/news/insider/finding-kenyon-barr-photo-exhibit-brings-razed-west-end-community-back-to-life. Accessed 24 Nov. 2018.

Curnutte, Mark. “Avondale Riots 50 Years Later: ‘It’s Never Been the Same.’” Enquirer, 9 June 2017, www.cincinnati.com/story/news/2017/06/09/avondale-riots-50-years-later-its-never-been-same/379214001/. Accessed 24 Nov. 2018.

Hatch, Charlie. “FC Cincinnati Announces Timeline for West End Stadium to Unveil New Design.” Enquirer, 29 June 2018, www.cincinnati.com/story/sports/soccer/fc-cincinnati/2018/06/29/fc-cincinnati-announces-timeline-west-end-stadium-unveil-new-design/745469002/. Accessed 25 Nov. 2018.

Hurley, Dan. “The West End at a Critical Moment.” Cincy, June/July 2018, cincymagazine.com/Main/Articles/The_West_End_at_a_Critical_Moment_5741.aspx. Accessed 22 Nov. 2018.

Kiesewetter, John. “Civil Unrest Woven into City’s History.” Enquirer, 15 July 2001, www.cincinnati.com/story/news/blogs/our-history/2018/06/08/civil-unrest-woven-into-citys-history/685960002/. Accessed 24 Nov. 2018.

Mason, H. Lee. “A Brief History of the Christian Restoration Association.” Christian Restoration Association, www.thecra.org/home/the-c-r-a-history. Accessed 24 Nov. 2018.

Suess, Jeff. “Our History: Old West End Theater Makes Way for Soccer Stadium.” Enquirer, 14 Nov. 2018, www.cincinnati.com/story/news/2018/11/14/former-west-end-theater-razed-fc-cincy-stadium/1997873002/. Accessed 22 Nov. 2018.

Swartsell, Nick. “Echoes of a Lost West End.” Citybeat, 6 Nov. 2017, www.citybeat.com/news/article/20981774/echoes-of-a-lost-west-end. Accessed 22 Nov. 2018. dengi-v-dolg.html