Any way you look at it, there was a lot going on in American culture in the 1940s and 1950s. There was a hot war and then a Cold War. American heavy industry had never been more dominant at home and abroad, and union membership was at an all-time high. Car manufacturing and ownership was on the rise, car ownership was spreading throughout the population, and cities were giving way to suburbs as the centers for rising population. Frank Lloyd Wright was designing houses and Charles Eames was designing chairs. In art, the rebellion of the Regionalists was simmering down—Thomas Hart Benton would come to be better known as Jackson Pollock’s teacher—and Mondrian was in New York, Calder was making sculptures, Gorky was painting abstractions, and Georgia O’Keeffe was well on her way into her flower paintings. How little of this you would know from visiting the Robert McCloskey show at the Cincinnati Art Museum! You would not say that he was an artist who had his finger on the pulse of America, though it would be fair to say that he understood remarkably well the things that quietly fascinated his audience, who probably saw projections of themselves in the inhabitants of McCloskey’s Alto and Centerburg and the other Brigadoon-like settings for his stories—or wished they could.

What are McCloskey’s citizens like? These are people who like leisure and labor-saving devices, though they’re not afraid of hard work. Sufficiency suffices; crises are typically marked by excess—too many doughnuts, too many books, too many whales. They are civic participants who like congregating. Their lives are marked by shared time and shared values. They are alone chiefly in moments of duty and moments of pleasure. (When things are really working out right, characters smile and close their eyes.) If you possess some civic authority, you could probably stand to lose a few pounds. One of the most heroic things to be is a storyteller. Genders are divided by areas of expertise, and the boundaries are firm but pleasant. And the kids! They are generally obedient, more likely to be out of line by accident or by being incompletely understood than by defiance or willfulness. They have things they are working on in private, and they have a quiet sort of ambition, looking for a break when others will recognize their value. They are patient, and in no real hurry to grow up.

McCloskey seems to have been patient as well. A well-trained artist—and everywhere we look in this show, we see signs of his considerable skill as a draftsman with a high-energy line—he had received recognition, but didn’t seem to have a career trajectory until he went to visit a distant connection (the aunt of a classmate), the remarkable editor May Massee, who worked on children’s books first at Doubleday and then at Viking. A powerful figure who shaped the careers of many illustrators, she helped foster the work of such mid-century figures as Don Freeman, Kurt Wiese, the D’Aulaires, the Petershams, C. B. Falls, and James Daugherty. She is famous for having told Ludwig Bemelmans, “You must write children’s books”—hence, Madeline. When McCloskey came to visit her, she seems to have said roughly the same thing to him. It took time to retrain himself, and it’s hard not to wonder how he supported himself in the years between Massee’s oracular recommendation and his first publication. Among the few flaws in this excellent show is the absence of his independent artwork before he turned to book-making (though there are examples of his independent artworks from later in his career).

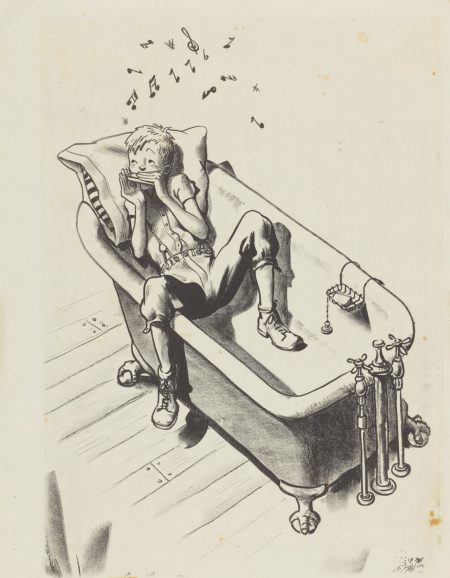

His first book was Lentil (1940). Massee had told McCloskey to draw what he knew, and in response, he decided to set his story in Alto, a version of Hamilton, Ohio, where he was born and grew up. A quick scan of photographs of Hamilton on the Internet make it clear that Alto is far more rural than Hamilton was. In McCloskey’s wonderful sketch “Walking on a fence, whistling,” our hero wears overalls, totes a slingshot in his back pocket, and goes barefoot. (He wears his shoes when he practices his harmonica in the bathtub at home, presumably for the value of the improved acoustics.) The town we can see in the background behind the fence has a Market that sells gasoline and Coca-Cola and a General Store that presumably sells everything else. There are some electric street lamps, but the only sign of a nightlife is a poster for “Perl O’the West” (Pearl? Peril?), a fictive movie, presumably. There are a few people on the streets, and a few more idling in front of the stores. McCloskey’s Hamilton seems to be a barely updated subdivision of Tom Sawyer’s Hannibal.

Lentil has friends, though there is no shame in being alone. Out in the woods by himself, he is inspired by nature to come up with melodies, “special tunes that were all his own.” At the proper moment, while dispatched to greet a famous man’s arrival by train, all of the town’s best-trained musicians are prevented from making the music needed to welcome him (it’s a long story, having to do with lemons and puckering up), and Lentil alone comes through. It seems rather like its close contemporary Dumbo (1941), without the blame and mockery. What matters is that a private talent turns out to have a public utility, and that this seems to epitomize the successful pursuit of selfhood.

There are core similarities between Lentil and Homer Price (1943), though Homer’s Centerburg seems a more sophisticated place. Homer’s bedroom is also his workshop where he labors to make a radio. His wall has pictures of sports heroes and pilots and trains, and a pennant for “State.” It is a more elaborate production than Lentil (it consists of six stories and is two and a half times as long), but also seems to feature a boy who distinguishes himself by utilizing the tools of his childhood (including the pet skunk Aroma who, like many of McCloskey’s animals, exhibits just the right mixture of curiosity and love of relaxation). Choosing from among many possible illustrations, the Museum places some emphasis on Uncle Ulysses, who invents for his lunch counter an automated doughnut machine that ends up being far too efficient, turning out piles and piles of doughnuts that must be gotten rid of. McCloskey seems drawn to the archetypal storyline of the Sorcerer’s Apprentice: sooner or later, there will be too many of something for people to handle. Perhaps it is a shrewd reading of childhood fantasies about, well, fantasizing, plus a vision of the direction of the middle class in America as it starts to have access to plentifulness. In one of the show’s best drawings, from a different Centerburg story, four males of varying ages and girths are sitting in a barbershop, only to be drawn from the sublime comfort of their various chairs by the strangeness of a passing vehicle. I was struck by the ease with people associate in Centerburg, and that folks are not on the street unless they have to be; his stories are filled with people who are looking out their windows (of homes, stores, or cars) as something remarkable passes by.

Like a line of ducks. Make Way for Ducklings (1944) and Blueberries for Sal (1948) are—at least they were in my household—McCloskey’s best-known books. They take his interest in the reconciliation between humans and animals to a new level, but in many ways they are strikingly different from the worlds of Lentil and Homer Price. The romance of the small town has been set aside, favoring instead the green spaces of a real city or the genuine countryside. No one comes of age or saves the day with a secret talent. Indeed, no one does really much of anything; they are books in which almost nothing happens. Interestingly, they are also both strongly matriarchal tales, where Mrs. Mallard has to do the right thing by her ducklings (and Mr. Mallard?), and where momma bear and Sal’s mother both avoid panic or anger at switched children, because they can recognize that bear cub and little girl are still both young creatures.

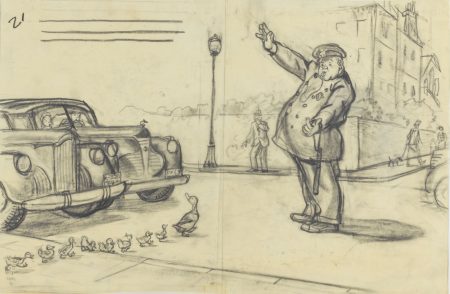

In Make Way for Ducklings, McCloskey’s most urban book, the ducks are all perfectly sure that they belong more or less where they are. It was another book for which McCloskey was given an assignment. At May Massee’s behest, he spent two years studying ducks at the American Museum of Natural History and in his living room, where he kept some as pets, learning more about their bodies and their movements, and sketching, sketching, sketching. I wish that the show had been able to share more of his sketchbooks. There are a couple of great pages of bears that he executed to prepare himself for Blueberries for Sal, but a quick look at the Internet will turn up some remarkable sketches of ducks that I wished we could have seen. In Make Way, people like to look at ducks and perhaps feed them, but are less ready, well, to make way for them. As we often see in McCloskey, people are in buildings or in their cars, staring out out dumbfoundedly at all that’s remarkable. The policemen are the book’s heroes, recognizing a kind of de facto citizenship for the duck family; they alone act with urgency. It’s interesting to put a book like this in the context of Walt Disney, who was also working hard around this time to work out the boundaries between animals in their native forms and in their anthropomorphized forms. (Bambi, for example, came out in 1942.) In the end, the message seems to be that if you treat the ducks like citizens, they are willing to be ducks as well, and swim in your parks and let you feed and admire them.

Even less happens in Blueberries for Sal—which is, presumably, part of the point—though it continues to explore the unspoken compacts between humans and animals. (We can see from McCloskey’s original sketches that the book’s title originally added the phrase “And for Bears Too.”) The story seems to be a parable about parenting of some sort: children will wander and parents need to be careful? But the tale seems to skirt being judgmental and instead, celebrate maternal common sense: there’s nothing here that mothers can’t handle. I thought that perhaps by this point of his career, McCloskey took less pleasure in creating vivid character types and was paying more attention to landscape. Blueberry hill is a triumph of inkwork with startlingly strong blacks for the silhouettes of distant trees. The panoramic arc of the hill’s horizon seemed to go on forever, from real space to something immense and mythic. In such a place, how can there not be enough blueberries for all?

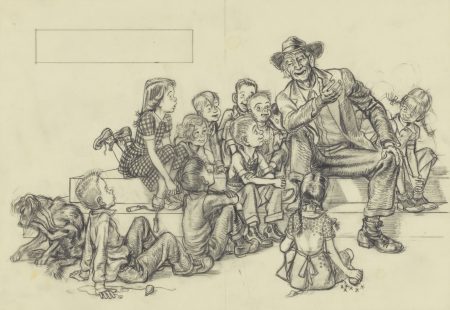

The sketch for the cover of Centerburg Tales (1951), the sequel to Homer Price, was very telling. Homer climbs up on a fence to pull the mail out of the roadside box, but in the background, we see what’s become of quaint Centerburg. Highway 56 runs through it—a road with a striped line! A large sign welcomes you to town, and as you drive in, you would see that an open field has been turned into a tourist camp. The implication seems clear: the charms of small town America are available to rent. The fundamental viability to such life is gone; people are willing to pay to experience a bit of this world, but they will always be outsiders–renters, not residents. The readers, presumably, are in the same position. The town lives on chiefly in stories. The kids gather round Grampa Hercules as he prepares to tell them a good one, and though they seem ready to believe every word of it, the storyteller himself seems to know that all tales in Centerburg are tall tales.

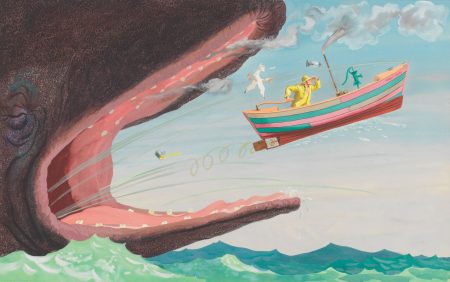

McCloskey’s final books are set in Maine, where he can observe a simple but functioning economy. It seemed to me that the Maine of his final books was a place where grownups go to grow up—but perhaps not completely. In his last self-authored book, Burt Dow, Deep-Water Man (1963)—done in striking watercolor and gouache—we follow the story of a Maine nautical “character,” who must keep mending and repainting his tiny boat. Burt is perhaps given to tall tales of his own. Story-tellers cannot resist story tellers. One fine day, he is out fishing and hooks himself a whale, whose tale he must mend with a Band-Aid after he works the hook out. Caught in a storm offshore, Burt seeks shelter for himself and his boat down the whale’s gullet, where he rides out the rough weather. How to get out? Burt takes those buckets of paint and splashes the whale’s gullet with one can after another, acting, as one sketch for the book has it “in an abstract primitive sort of way” that would have been recognizable as a Jackson Pollock. Irritated by the paint, the whale spits him out, but the story notes that “it was the first time he’d ever had the chance to express his personality in paint.” In the very end, Burt, back out at sea and safe from the storm, encounters a school of whales, and is obliged to make sure that every one of them has a Band-Aid on his tail. The animals need attention and people need stories. That’s the deal.

In a way, the exhibit does take us from American regionalism to abstract expressionism after all, from the drawing style of Thomas Hart Benton to the painting style of his most famous student. It may capture, when all is said and done, the transition between a world where people are driven by nostalgia for small town America to the world where that nostalgia is commodified and offered up for sale. It’s a timely show. People are more interested in historic book illustration than ever. I belong to a Facebook group called The Golden Age of Illustration that is coming up on 80,000 followers. The McCloskey show may also be evidence of a nostalgia for tangible books in an electronic age. It shows us the alchemy whereby hand-drawn sketches are transformed into finished illustrations and finished illustrations are put together to make books, things you can hold in your hand. There is a small library of McCloskey’s books on a big table in the gallery. There’s a roll of drawing paper next to the pile, and a stock of pencils, where children drew whole-heartedly and adults impatiently waited their turn to do the same.