Super Cooper: Art without Words

By Keith Banner

In a New York Magazine article about the recent opening of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute’s exhibit “Punk: Chaos to Couture,” Nitsuh Abebe writes: “In music, punk remains what the critic Frank Kogan calls a ‘Superword,’ a term whose main purpose is for people to fight over what it should mean, using it as a ‘flag in a bloody game of Capture the Flag.’ It’s a concept like ‘freedom’ or ‘the one true Church’ or ‘real Americans’: to invoke it is to advance a vision of what it entails, and duke it out with competing visions.”

Semantics becomes destiny in other words, and all the antics, epiphanies and realities get swamped by what we call them. “Superword” is also a great way to conceptualize that other weird little cultural red-headed stepchild: “outsider art.” Anytime I’ve ever been to an “outsider art” conference, fair or symposium, capturing the “outsider” flag is always of optimum importance, especially to curators and academics. It’s like naming and claiming something becomes the something you’re trying to name and claim, a magical alchemy that doesn’t really deliver any help or insight, just fogs up the issue and makes you feel like you did something.

The mainstream artworld considers “outsider art” a sweet little nuisance at best (take a gander at what the MOMA wants to do with the American Folk Art Museum as a general, guiding metaphor), and outsiderness’s representatives and apologists become predestined wannabes. They end up squabbling at the kid’s table at Thanksgiving.

So why not get rid of the whole idea?

Because, I guess, if you don’t name something, if you don’t claim it as ‘something,’ then it often becomes what everybody already seems to think it is: nothing. You have to figure out what an artist who doesn’t have a pedigree, who does not have access to networking and professionalization opportunities, but who does have talent and energy and motive – you have to find a way to help them get noticed, not so you can play the “capture the flag” game, but so they can prove to the world what they are made of. And that means you probably have to get rid of the superwords that are in the way, while understanding that the real game is outside of the outsider realms, outside of semantics, and outside of superwordiness.

That’s what’s so great about Courttney Cooper being in a two-person show at the Cincinnati Art Museum (“Cincinnati Everyday: Cole Carothers and Courttney Cooper,” opening May 25, 2013). It is a joyous occasion for me, as one of the cofounders of Visionaries + Voices, a non-profit organization for “outsider” artists with disabilities. Matt Distel (currently moving from his post as the Executive Director of V+V to Adjunct Curator of Contemporary Art at the Cincinnati Art Museum) made this happen. “Everyday” is truly an epiphany culturally. It allows Courttney to slip outside of outsiderness, and it also allows all of us time and space to contemplate the pigeonholing we often automatically resort to when trying to figure out what kind of people can make the kind of art shown and celebrated in museum spaces.

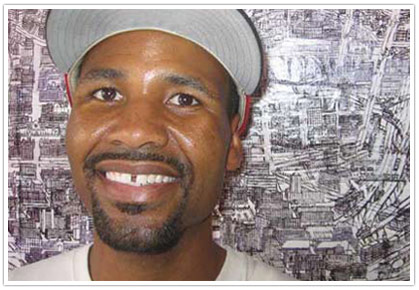

Integrally linked with V+V (he makes a lot of his art there), Courttney could be seen as a prime example of “outsider art” codification. African American, working class, labeled with a developmental disability, he creates large-scale, hand-drawn maps that are mesmerizing to look at and yet maintain a home-grown sense of obsession and delight. His work is sophisticated and complex, but also easily accessed and enjoyed at many levels: as design, poetry, even as actual maps (many folks from Cincinnati who first come upon his maps often say they can see the street they grew up on within them). Courttney is able to recreate the contours and crevices both of the inside of his brain and the outside of his hometown. However, in placing Courttney’s work in context with the work of a more pedigreed artist, Distel and the Cincinnati Art Museum are allowing all of us a chance to ask a really simple yet completely necessary question, and the answer of course is pretty easy. Both artists in “Cincinnati Everyday” deserve to be there.

I met Courttney in December of 2003, right when Visionaries + Voices was in its promising beginning stages. A few months before, we’d incorporated as a non-profit, gotten a studio-space at Essex Studios, and I’d written a grant proposal that was funded by Greater Cincinnati Foundation for a full-time Studio Coordinator. We were on our way. At the time, I didn’t really think a lot about what “outsider art” or what any kind of art meant. I was just intoxicated by the rush of events as a group of us pulled together in a makeshift movement in order to assist artists like Courttney who were not even considered “artists” by many folks.

The whole reason behind V+V came from circumstance. I’m an artist and a writer who has a full-time job doing social-work, and as I and Bill Ross (another artist/social-worker and my partner) were helping people with developmental disabilities we came across great artists. I was vested from that experience, so that the establishing of an organization to help others see what these artists are capable of seemed like a necessary next step. “Outsider art” was just a superword I was getting used to back then. I stumbled upon it because I knew so many artists who fit that bill, and I figured since the nomenclature and market was already there why not go with it. But back then I also didn’t understand the caste system involved in the artworld. Assisting artists to lay claim to an “outsider artist” identity isn’t really a great career move. It also often convolutes the enjoyment of the art through a propensity for depending on sentimentality, biography and exoticism to explain it.

Cheryl Beardslee was Courttney’s high school teacher at Western Hills, and I along with some other people from V+V went over to Western Hills back in 2003 to do an art-making project with some of her students. Even though Courttney had graduated from high school a few years before, and was working full-time at Kroger’s in Walnut Hills, Cheryl had maintained contact with him, and she invited Courttney to be a part of the collab. When I first saw Courttney I was impressed with how polite he was, a thin, courteous and quiet gentleman. We had big wood panels for the students to paint on, and Courttney went right to it. He picked up a marker and started drawing robots and cars and buildings. It was amazing. The other students contributed, but Courttney stuck out like a master. And after finishing each drawing he was all smiles, going on to the next.

We got to talking, and Cheryl told me that Courttney happened to live just a few blocks down from Essex Studios, where V+ V was. After we finished up, I volunteered to drive Courttney over to V+ V, to introduce him to the space and the other folks there. He said yes. So we got into my minivan and drove over to Essex. He was silent on the way over, again all smiles, a little fidgety but every time I asked him a question he answered enthusiastically.

“Do you like working at Kroger’s?” I asked.

“Yes I do.”

He spoke with a monotone, breathy assuredness, and as we drove his eyes seemed to be taking in the scenery like hungry mirrors, so wide open it was almost funny. It was so easy to like this guy.

I parked in the back lot. We got out.

“You just live down the street right?”

“Yes I do.”

“You could come here whenever we’re open and you have time.”

“Yes I could.”

“That’s great,” I said, excited for him.

“Yes it is,” he said.

I unlocked the backdoor with my key, and we walked to where the studio was. I opened the V+V door for him, and inside were four or five people who had started coming to the studio regularly to make art, and Shawna Guip, the Studio Coordinator we’d just hired. One woman was working on a ceramic sculpture. Another older gentleman was working on a collage. Somebody else was painting near the back windows. There was a huge table that had just been donated, the size of a vast pool table, shiny mahogany, and everyone was seated around it.

I remember asking Courttney if he wanted to draw.

“Yes.”

Shawna got some paper and a box of pencils, but once he had the paper he pulled out a black Bic ink-pen from his pocket and just started drawing, head-down, like he was diving into his next world.

I didn’t really know anything about him, except that Cheryl liked him a lot, and he lived down the street from V+V. There was no intake process, no billing procedures at this time. Just lucky happenstance. I stayed for a little while and watched him, and everybody else, make art, and I felt so incredibly happy right then. It was like this was meant to be. And that hardly ever happens in life.

Since then, of course, V+V has grown, thanks to the efforts of a lot of people, and to foundations, donations, government funding, fundraising, and all of that. I still think back to that day though, and realize that’s actually what it will always be about for me: that moment when I took Courttney there for the first time, watching him figure out where he could flourish in a world that really did not pay a lot of attention to him and to what he can do.

Courttney has used V+V in a way that has allowed him to be productive and a part of a social network, and also as an opportunity to prove himself as an artist, without the need for descriptive superwords. He expanded his mode of operation because there was more real estate. V+V had that big table that he could stretch out on, and his repertoire grew because of it. His deeply personal and astonishing drawings of maps took on an epic scale because he had a neighborhood place to go to do it that allowed him to expand, with people that cheered him on. This happened because he had a disability and V+V was created to help him, but V+V did not create him. I’m thinking whether or not V+V opened its doors, Courttney still would have found a way to create his art and make happen what he needed to happen. That’s my hope at least. It’s because of his intense talent and drive. In other words, and these aren’t super at all, Courttney is an artist not because he has a disability or because he goes to V+V or because of anything other than the fact that he himself willed himself into being one. When you place some one’s spirit and talents into the realm of superwords like “outsider artist,” it’s easy to forget that. Courttney is an artist because he wants to be. He needs to be. And we’re all the better for it.

Great article Keith! I couldn’t agree more that Courttney’s awesome drawings deserve to be seen in a “contemporary art” context (whatever this means!). As such, my contemporary art gallery in Chicago, Western Exhibitions, included his work in a three-person show last summer:

http://westernexhibitions.com/current/2012/5_IndirectOb/index.html

Great meeting you and Bill at the CAM opening last week.

Cheers,

Scott

Great article Keith! I couldn’t agree more that Courttney’s awesome drawings deserve to be seen in a “contemporary art” context (whatever this means!). As such, my contemporary art gallery in Chicago, Western Exhibitions, included his work in a three-person show last summer:

http://westernexhibitions.com/current/2012/5_IndirectOb/index.html

Great meeting you and Bill at the CAM opening last week.

Cheers,

Scott