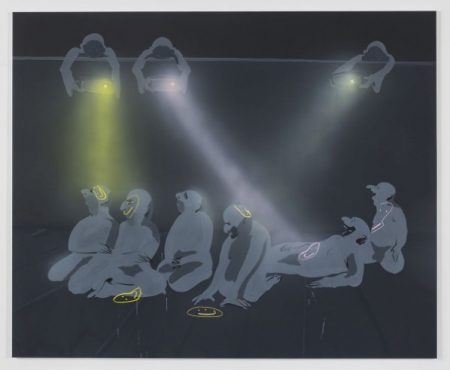

At a whopping eight feet wide and predominately a Mars Black that tempers into the Payne’s Gray realm, Projections (2015) presents itself (similarly to all of Madani’s paintings, animations, drawings and music) as a viscus and intuitive—quick or even hasty— figurative narrative depicting male figures participating in some sort of tragic comedy. Carbon Black lines leading from the bottom corners of the composition toward the center in a joke-y depiction of one-point perspective work as an indexic point of reference toward space, rather than working to actively articulate a sense of illusionistic space.

At first, the placement of these lines in conjunction with the colored lights coming from above (lights coming from realistically rendered projectors) illicit an idea that these are actors or some willing participants in some vague act of theatricality— the space that these six main characters inhabit is a sort of stage. There are six figures all within the center of the composition. All of which are in some assorted pose ranging from seated, cross legged, kneeling, or in a languid lying position. All of which are presumably nude (there isn’t an indication of clothing, just the abundant sense of galkyd and smooth, rotund bodies—no genitals are exposed), all approximately middle-aged and, some bearded, all balding. Their expressions differ widely from blind amusement to utter despair.

Smiley-faces in yellow and pink are projected upon the six seated figures. The smiley faces aren’t depicted as a flat graphic, in their true circle with a pair of eyes and a mouth, but as an image that is being projected with light onto a curved surface. Some of the smiley’s hit their target: on to the face, neck, or chest of the actor or man seated below. Some miss their target, instead hitting the leg of another actor—and in the case of the central, and saddest figure—hits the back of the head and then reappears on the floor in front of the actor or figure. Making the projection of the smiley face known to him is possibly the cause for his misery as he is seen kneeling with his hands on the floor, gazing downward and experiencing anything from aching despair to a subtle and quiet disappointment. Theoretically, the pronounced despair in this particular character, having seen the “smiley face” offers the viewer a Platonic “seeing” akin to the Allegory of the Cave. The figure is saddened by his recognition of his own reality.

The projectors above the central figures are being held by hand by three other men—these seem more malicious and cavalier. They appear to be coming from behind a wall, suspending the projectors over the central six figures, and pointing the light where they need it to go. These figures, also bald, aren’t men with characteristics akin to those below. They are the same light gray shade, but their faces are blacked out, presumably because they are leaning over this wall and whatever natural light source that’s insinuated misses their faces. Upon close inspection, these three figures have smiley-faces for a face. There is no nose. There is no expression. There is no indication of ethnicity (the figures below are vaguely Middle-Eastern, common for the Iranian American artist, Madani) age, or humanity for that matter.

Tala Madani has a reputation for inverting, critiquing, and lampoons contemporary life in a style that is both intrinsically funny and starkly aggressive. Madani is highly successful utilizing materials, or the manipulation of them, to indicate or validate conceptualization. She illustrates rich narratives in flat, non-illusory spaces as a conscious retraction from Renaissance studies of perspective—as well as an embrace of flat or layered realizations of space found in Islamic or Middle Eastern compositions. Madani represents male characters as an inversion of the male gaze—discrediting art history’s deployment of the female figure as vessel for symbolism ranging from the lustful to the economic. The loose, gestural, viscous quality of her paint probes the figures to appear fumbling, sloppy, and irresponsible—but also playful—they’re often child-like in their naiveté—if they aren’t actually babies, which she also utilizes frequently.

In preparation for her mid-career retrospective at MOCA, Los Angeles, in May 2021 and at Kunstmuseum, The Hague, The Netherlands in 2021, Tala Madani and Nathaniel Mellors (coincidentally her partner) sat down for a discussion documented for Flash Art,[1] and in the first moments of the discussion, the two artists enter into the topic of death in Madani’s work. In Projections, death appears in the realization of falsity in how we are coerced into presenting ourselves to the world— a projected joy that inhibits true joy. To quote Mellors, the figures here, have a painted “physical vulnerability that’s very invulnerable. . . A lot of the figures are like cartoon figures that you can smash and break but they don’t die. . .there is, perhaps, an iconography of death to [them].”

All of this makes me consider our chosen symbolism and timeliness. How will Madani’s figures be translated in 2089? Within the interview mentioned above, Madani mentions a painting of a P95 mask that she recently completed in light of the pandemic— a response to feeling overwhelmed and distracted by the daily news. She makes mention that in a few years, those paintings of masks might not register as particularly weighted—as they do now. This observation about the frailty of a symbol is relative to the fragility of her figures, the figure being the most weighted within the iconography of painting. So, how will they be translated in 2089 and, more importantly, does it even matter right now?

Projections, 2015

oil on linen

80 x 98 1/4 x 1 3/8 inches

(203.2 x 249.6 x 3.5 cm)

image courtesy of David Koransky Gallery’s Website

–Megan Bickel

[1] “Invulnerable Vulnerabilities: Tal Madani and Nathaniel Mellors Discuss Life and Art in the Time of the Virus.” Flash Art. No 330, Volume 53. April-May, 2020.