What makes Jean Dubuffet’s art so captivating? Dubuffet Drawings, 1935-1962, which closed April 30 at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles, offered insight into elusive qualities that vivify his work.

The rawness characterizing Dubuffet’s oeuvre is especially palpable in his drawings. This medium’s immediacy seems ideal for embodying his characteristic roughhewn aesthetic.

“I must learn how to draw,” he wrote in 1944. “Of course when I say draw I’m not to the slightest degree thinking of faithfully reproducing objects; … no, it’s a matter of something quite different: to animate the paper, to make it palpitate.”

This exhibition demonstrated his achievement of this goal. Its approximately 100 works divided into sundry categories illustrated his technical versatility and breadth of material exploration.

Having dropped out of art school in 1918 after 6 months of study, the former wine merchant devoted himself to art in 1942 at the age of 41. As spontaneous as his works appear, Dubuffet approached his material experimentations with considerable technical rigor. His relative lack of artistic training may have afforded him liberty from academic convention; but it also necessitated autodidactic rehearsal in perfecting his idiosyncratic inventions. In North Africa, he made his own paint with gum arabic, which supposedly required months of practice before he felt proficient in the medium. His Corps de dame (Lady’s Body, 1950) series betrays a rather academic inclination: experimenting with different modes of representing the same classical subject.

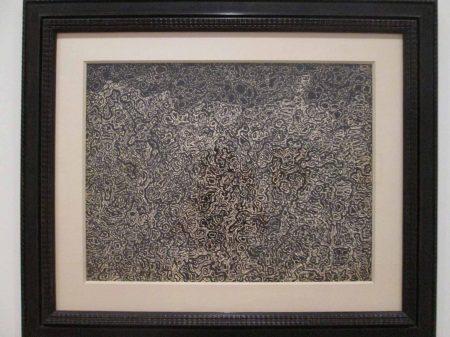

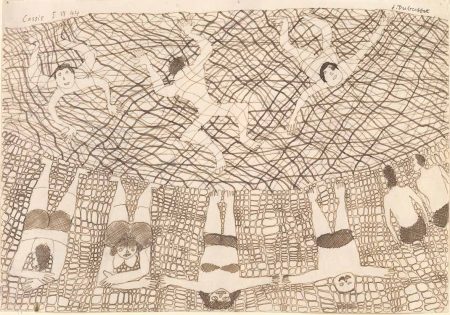

Though diverse, much of his drawing is united by certain commonalities. Dubuffet possessed a flair for allover compositions and pattern-like busyness. Obsessed with representing infinity, he employed various methods for creating profusions of detail, alternating between total manual control and chance. Sometimes, he meticulously drew each line and dot. Other times, he developed less labor-intensive techniques like “imprints,” monoprints created by pressing paper against an inked table covered in textured objects such as foil, sugar, or leaves; or collages assembled from drawings, imprints, or actual objects such as butterfly wings. He often covered nearly every square inch of his pictures in densely packed expressionistic marks, drips, washes, lines, collaged fragments, or combinations thereof.

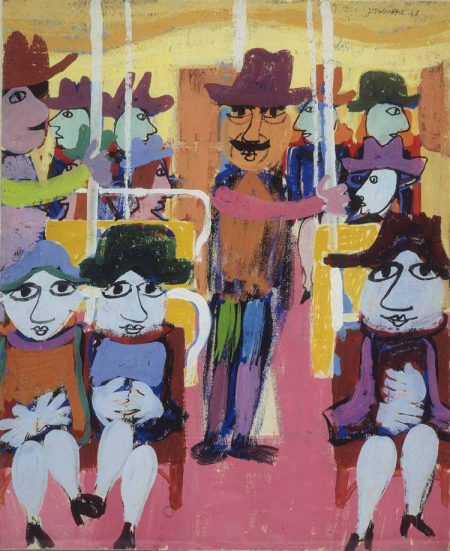

In some pieces, pattern occurs by way of repetitive form. In Le Metro (1943), a series depicting people on subways, the viewer’s focus bounces from face to face, similar to the way it would inside an actual crowded subway car. These drawings are among his most painterly, consisting of color blocks embellished by linear elements.

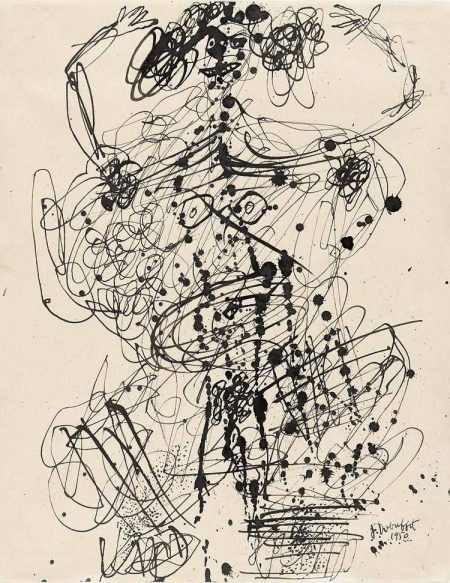

In later works, he employed line more emphatically. Lines act as lifeblood, energizing and sewing together compositions while acting as diffuse centers of attention. “It’s a matter of learning how to make a line, a little line five centimeters long: but a line which lives, whose pulse beats,” he continued his 1944 statement above. Seaside drawings from that same year portray pebbles, sand, and water as stylized webs of lines intersecting with bathers.

Later pieces, especially a series titled Radiant Lands, feature linear networks that overwhelm horror vacui compositions bordering on total abstraction, as in Paysage au Lapin (Landscape with Rabbit, 1952). Others involve lineations that are equally busy but delimited, as in Géologue à la loupe et la canne (Geologist with Magnifying Glass and Cane, 1952), where tangled scribbles delineate titular figure and terrain against blank background.

A wall label explains: “Dubuffet’s Radiant Lands express his vision of the world as an amorphous substance, ‘a continuous broth, which has the same taste everywhere.’ But he also described them as ‘landscapes of the mind…They aim to show the immaterial world which dwells in the mind of man…'” Indeed, the tangled webs seem as diagrammatic of cerebral matter as of terrene topography. In their dense unfathomable abstraction, these pictures seem to present views that are simultaneously close up and far away, microscopic and telescopic, ultimately illustrating the seemingly pointless complexity of life.

Dubuffet’s eloquent quotes betray the fact that his deceptively simple, apparently untrained work was actually founded on sophisticated intellectual ideas. Another museum label says that Dubuffet began the Radiant Lands series while living in New York: “‘I have little contact with the city,’ he wrote, ‘as I live permanently…in vast uninhabited and inaccessible landscapes, deserted escarpments, which I paint all day long. It’s rather funny to come to the most densely populated city in the world to paint these no-man’s-lands.'” Clearly, the artist was well aware of ironies inherent to his work and self-presentation.

It’s almost paradoxical that Dubuffet’s self-aware preoccupation with his anti-academic creative potentiality as a largely self-taught artist led him to study, collect, and categorize the art of psychiatric patients and folk artists, coining the term Art Brut while creating his own art from its inspiration. In a 1962 review, Hilton Kramer pointedly unmasked this incongruity: “There is only one thing wrong with the essays Dubuffet has written on his own work: their dazzling intellectual finesse makes nonsense of his claim to a free and untutored primitivism,” Kramer observed. “They show us a mandarin literary personality, full of chic phrases and up-to-date ideas, that is quite the opposite of the naive visionary.”

Somehow, though, Dubuffet’s work seems to escape pretentiousness; his explorations feel sincere and mysterious. For instance, Le pays hanté (The Haunted Country, 1954), a monochromatic imprint assemblage depicting a lone skull-faced figure in a moonlit landscape populated by cryptic forms, gives the impression of a picture that one could gaze at every day for weeks and still not comprehend its entirety. His are works of dichotomies: existential dread and everyday comedy, sophistication and crudeness, intellectual and primal, infinity and nothingness. Rather than detracting from his work, his polar self-awareness augmented his eschewal of education, allowing him to become one of the rare artists knowingly, but naturally, bridging the worlds of “insiders” and “outsiders.”

“Dubuffet Drawings, 1935-1962” was on view at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles from January 29 – April 30, 2017.

–Annabel Osberg