The Fetish Line:

“Andy Warhol: Athletes” and “The Art of Sport” at the Dayton Art Institute

By Keith Banner

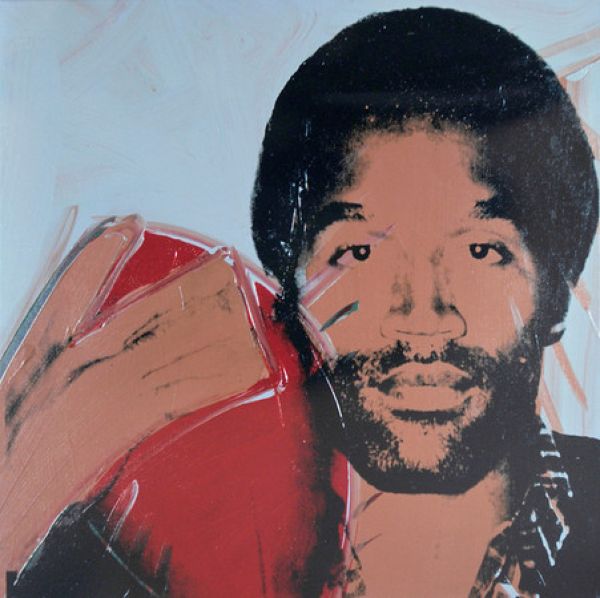

“He’s SO beautiful,” Andy Warhol swoons in quoted text next to his Day-Glo portrait of O.J. Simpson in “Andy Warhol: Athletes,” a show of commissioned pieces Warhol did in 1977 installed on aqua walls at the Dayton Art Institute.

All of Warhol’s icons of sports have a nostalgic, slightly sad, phosphorescent plasticity – as if they were created out of boredom, codified, self-important doodles glossed over a cavalcade of superstars. He meditates through glamorous graffiti – paint swipes and swirls like clown make-up smeared all over 20th Century sports gods and goddesses, including Chris Evert, Dorothy Hamill, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Jack Nicklaus, Tom Seaver, and Muhammad Ali. Not only are the figures he was commissioned to Warhol-ize nostalgic (a scrapbook of late 70s celebrity), Warhol’s yearning to glamorize and fetishize them are as well. The lovely, awful aqua walls of the museum have an old-school art-deco Miami feel, a freaky decadence that somehow turns the work into metaphors as opposed to similes. Warhol has created a plastic Pantheon here, not really referencing the greatness of each athlete’s accomplishments, but registering his love of how they are loved by their fans. He is turned on by fame, not by agility or grace or prowess.

“SO beautiful” means something far more complex and creepy than physical or even athletic allure. Warhol is talking about, and creating art because of, each athlete’s connection to mass media and their claim to an overarching superstardom he always was pursuing in his art. In other words, their images are not really the point. What he does to their screen-printed visages is. He is marking his territory. Those purples, greens, silvers, and flesh-tones smeared around and into the faces of each figure become a sort of transmogrification, a way to find Chris Evert and Mohammad Ali, etc. interesting enough to worship. Muscle, flesh and face get flattened into cathedral décor.

This is always Warhol’s strategy, from the golden Marilyns, the ruby-red-lipped Elizabeths, and the slapdash gun-slinging Elvises in the early 1960s to the sad tumultuous “Pop Art” portraits of the 70s and 80s, in which anybody with enough cash (including Farah Fawcett, Liza Minnelli, a bevy of fun-loving old rich couples, and so on) could ask Warhol to transform them into Warholian avatars, creatures of the Warhol Red-Carpet Night. Not to mention his appropriation of Chairman Mao, transforming the Chinese dictator into a candy-colored clown funny and scary enough to be laughed at and feared simultaneously. That process of conversion is total kitsch in the “Athletes” series. The tarted-up portraiture is an accessory for the nouveau riche, an indicator of a desire to be bigger than you actually are, and yet that desire is always the point. Warhol was a champion at taking banality and desire and channeling all of it into a facsimile of greatness. But the “greatness” is always on his terms; he is a philosopher of nothingness pumped up and decorated into a disco manifesto.

“Andy Warhol: Athletes” truly is a sight to behold because it has that synthetic hyperbolic Pop-ness Warhol eventually turned into a way of speaking, creating, living, and even dying. The “Athletes’” pictures have a totally superficial quality that Warhol uses to satirize and honor at the same time. That’s his genius, in a nut shell: the ability to parody and worship without losing that masterful sense of flash.

The show directly connected to “Athletes” at the Dayton Art Institute, called “The Art of Sports: Highlights from the Collection of the Dayton Art Institute,” is another species of animal altogether. A little pompous, a little silly, but entertaining, this one has been curated with a kitchen-sink kind of spirit that is both fun and a little boring. There are Salvador Dali playing cards, a Jasper Johns target, a 19th Century painting of hunted kills by George Hetzel, a spastically colored lithograph of a horse race by Leroy Neiman, and so on. (Why a parcel of Robert Longo’s 80’s iconic “Men in the City” series got included is beyond me; I guess you can say the film-noir-inspired, faceless, contorted, well-dressed bodies in clipped spaces Longo does are somehow related to sports, but truly they are just crisp, clean wisps of early 80s art-world melodrama.)

It’s as if someone just went through the collection and pulled out whatever came closest to the “sports” concept. Which is fine, I guess, but the one body of work that stands out the most, when juxtaposed to Warhol’s “Athletes,” is Ronald R. Geibert’s photographs. He has quite a few lovely and particular pieces in “The Art of Sports” that truly live up to the title. Artfully shot and skillfully felt, the images he goes after (of racetracks, body-building contests, gymnastics routings, and football games) have a Diane-Arbus tenderness to them that shoots through the confetti and exhaustion inherent in Warhol’s world.

Geibert’s “Competitors,” a moody, 1984 color photograph, depicts an injured player sitting on the sidelines of a football game with a broken leg. He has no expression on his face, but there’s a sort of question-mark across his body, as if the whole atmosphere of the picture has been consumed by his sudden loss of function. It’s an image you might see at an actual game, only frozen in time, and through that freezing process we get a glimpse of what it means to be an athlete ostracized from the game. The player’s motionlessness is the poetry here, and Geibert’s eye gives us a glimpse into the meaning of not knowing what’s going to happen next, now that everything the player might have been living for has been taken away because a bone broke.

That broken bone, when split-screened with Warhol’s “SO Beautiful” sports-celebrity concoctions becomes a sort of symbol that goes beyond demarcation into a moment of loss that reiterates the reason why people play sports. They want to escape their bodies by using them. Warhol wanted to escape his body too, I bet. But all he could do is find ways to worship the escape attempts.

Ronald Geibert, not Robert. Let’s get that right if you’re going to talk about his work. Thank you.

Ronald Geibert, not Robert. Let’s get that right if you’re going to talk about his work. Thank you.