Chinese and Japanese art come from radically different traditions and assumptions than Western art. “Chinese painters are always painting essences, not likenesses,” according to Curator Daniel Brown. Because Asian art looks for essences and is highly reductive, artists radically reduce the visual information included in their work to the barest of essentials. In this sense, the Western word minimalism describes a basic tenet of Asian art. Paintings by Kay Hurley, Paula Risch Head, Stacie Seuberling, and Trish Weeks are examples of this minimalist, reductivist practice. Each of these artists also paints essences, the feel of a scene, rather than a defined likeness of a scene. Although bright color is frequently used in Japanese art, it’s rarely used in Chinese painting. Painter Lisa Molyneux’s landscapes appear more and more Chinese each year, partly because of the subtlety of her color, and partly because of her near-minimalist approach to space, composition, and gesture, where she captures the essences of the landscape.

When Abstract Expressionism hit the American, and then world stage, the visual similarities between what’s known in the West as “the gesture” began to both resemble and serve the same painterly function as the calligraphic mark in Asian art. Since Asian artists are trained to use their entire arm when they paint, and since Abstract Expressionist painters also may use their entire bodies (it’s thus called Action Painting), we propose in this exhibition that the gesture and the calligraphic mark are nearly one and the same in their intentions and execution in the work of these sixteen artists. A kind of hybrid style emerges, a blend of Eastern and Western techniques and aesthetics. The gesture and the calligraphic mark are the defining structural/formal device in the work of the artists in this exhibition; about half the artists are more influenced by Chinese art and the remaining by Japanese art.

We can also call this hybrid, globalized type of painting calligraphic expressionism, simply replacing “abstract” for “calligraphic”; that sweep of the arm we find in American abstraction also dominates in the work of Bukang Yu Kim, Valerie Shesko, and Frank Satogata. Shesko’s and Kim’s work are more Chinese inspired, and Satogata’s, Japanese. Japanese artists paint flatly and decoratively (though the word decorative is used with the highest praise in the Japanese tradition.) If you look at Satogata’s paintings, you’ll see those rapid-fire gestures associated with calligraphy and abstraction; it appears as if flowers and flowering trees are bursting into growth right before our eyes. Kim’s darker, more brooding landscapes draw from the Northern Song and Tang dynasty Chinese painters, considered the finest paintings the Chinese have ever created; she, too, is reductivist, calligraphic, and abstract in her work. Shesko’s work uses overtly calligraphic marks as well as Western gestures, and she, too, is a minimalist/reductivist. Kim Flora’s paintings show even more influences from contemporary Western art, but you can see their groundings in the Chinese aesthetic in particular.

Adam Hayward’s paintings draw clearly from the asymmetric tradition in both Chinese and Japanese art, and Matt Metzger’s investigations into the heavens follow very clear Chinese philosophical and aesthetic traditions. He, too, uses multiple perspectives and radical reductivism in his paintings and interweaves elements of American Abstract Expressionism into his work. And in the context of this exhibition, photographs by Kent Krugh and Jens Rosenkrantz also look very Asian; the lack of color in the Western sense (though the gradations of greys and blacks is very Chinese) is a defining characteristic, as is the emphasis on one tree (Krugh) as a stand-in for all of Nature, which the painters of the Southern Song Chinese Dynasty did with the greatest of effect, where one element in nature is a symbol for all of Nature, microcosm symbolizes macrocosm. Rosenkrantz’s blacks are unusually rich and very Chinese. The fogs and mists are common elements in Asian painting, particularly Chinese, as the delineation of space in Chinese art is totally different from Western paintings. No one point perspectives for the Chinese or Japanese. The Chinese paint space vertically and the Japanese utilize flatness for similar effect. The Japanese frequently over scale natural elements, like birds and flowers, and put them onto gold leaf screens for flatness, but the result is similar to those painters of the Southern Song Dynasty conceptually. And the Japanese aesthetic is defined by the emphasis on the transient; early spring and late fall thus best define what they paint, which refers us back to the work of Frank Satogata in particular.

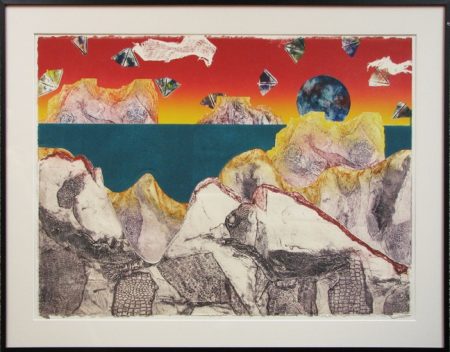

Mary Woodworth’s collotypes are very flat, very Japanese, but utilize the sense of Chinese space in her work, all of which seem nature-inspired and are also reductivist. Jack-Arthur Wood’s very flat prints continue a very contemporary interpretation of Japanese prints, which are indeed their main source in his work. And Kevin Kelly’s landscape paintings seem very contemporary and very Japanese; he frequently uses elements of subtle asymmetry in these paintings, is radically reductivist in his compositions–he eliminates all kinds of unnecessary visual information and/or clutter — to create a very clean, pristine, Japanese-seeming effect and his paintings could easily be turned into Japanese screens. He over scales the way Japanese painters often do, as well.

Defining what beauty is in art and in nature seems an unnecessary exercise. Many would agree that our sense of aesthetic pleasure comes from/derives from our appreciation of nature and of its shapes, forms, colors, seasons, compositions; most paint colors come directly from nature. Henri Matisse maintained that giving joy and/or pleasure is one of the primary purposes of making art–and we note that he, too, was a reductivist and a great colorist. Looking at beauty causes an internal serenity within us, a kind of meditative presence, even an otherworldly glance towards the heavens, the earth, and to the most pastoral types of landscapes included in this exhibition.

Almost all of the artists in this exhibition are mature, at mid-career or beyond (with the exceptions of Jack Wood, Kim Flora, and Lisa Molyneux). A kind of hard earned simplicity dominates in all the work, a trait I find uniquely Chinese and/or Japanese in intention and execution; these traits are timeless in Asian Art, and thus differ from the fleeting “isms” of so much of Western art. Nature seems best suited to the curve, the curvilinear, and you’ll see more curves than straight lines throughout the work in this show; the curve is often associated with the female, or feminine archetype, from which, perhaps, comes the expression Mother Nature. Cincinnati Art Galleries is pleased to present the work of these sixteen regional artists and the influences of Chinese and Japanese traditional/classical painting on their work.

–Daniel Brown