“‘I’m living my life out in a cell in a row of beehives and when I wake up and think of it like I did last night it seems to me I’ll just go crazy! …All these flats just exactly like this one—all of ’em with exactly the same maroon in the furniture and rugs, the same beds that fold up behind false doors, the same kind of linoleum in the kitchenette, the same records for the phonograph, the same programs every night on the radio—'”

–Young Mrs. Greeley by Booth Tarkington, 1929.

Nearly 90 years later, has anything changed? Banal impulses only seem to have gained momentum in driving that sameness of which Tarkington’s protagonist complained. Bland new housing tracts sprout up more prolifically than ever before, the residences therein built ever more alike, tinier, closer together, yet ever growing more expensive. The more possibilities progress bestows upon society, the more our individual choices and pleasures, paradoxically, become eroded. Social media fans flames of ideological conformity among tribalistic cliques. Stark income inequality is only increasing as technology advances.

Though nothing new, these notions are, perhaps, increasing in their urgent relevance. “There’s never before been a society in which everybody is under constant observation, constant surveillance and in which they’re constantly receiving this stream of experience that is being dynamically adjusted to find ways of manipulating them,” Jaron Lanier recently observed[1]. Through the lens of robotization and digital technology, Lanier and many other contemporary theorists are sharpening dystopic notions similar to those propounded by George Orwell, H.G. Wells, and Aldous Huxley. Architect Rem Koolhaas sees a latent “wave of authoritarianism in the name of saving the world.”[2] One could fill a library with recently published tomes of cautionary tales about burgeoning banes of the digital age.

Given such topics’ current prevalence throughout other disciplines and popular culture, it’s no wonder that a growing number of visual artists are also addressing digital technology’s dubious societal effects. Spanning a wide range of media both old and new, many of these artists are picturing potential dehumanized futures. Evincing this trend, three coincident shows by Matthew Lax, Gregory Bennett, and Ian Davis presented remarkably similar visions of the future at different Los Angeles galleries. These artists unite in elaborating claustrophobic never-ending sterile dystopias where humans, devolved into robots or dummies, are relegated to mere pawn-like motifs in all-encompassing patterns.

Matthew Lax’s video installation, which closed Nov. 18 at Los Angeles Contemporary Archive (LACA), featured Brunt Drama (2018), a single 7:30 digital video loop projected on a freestanding double-sided screen. Neighbored by bookshelves, Lax’s glowing projection screen appeared as a holographic high-tech void in the middle of LACA’s darkened library-gallery. The video features lavender crash dummies performing repetitive, seemingly pointless tasks in mechanized groups and pairs against tenebrous backgrounds of nothingness, while simple audio effects sound as clinically hollow as pins dropping in a bare room. Mysterious subtitles, often bearing inscrutable equations, neologisms, and clever misspellings, satirize the euphemistic nebulousness of marketing newspeak and phony personal platitudes. Underscoring monotony, such text snippets are duplicated in mirror images so as to be legible from both sides of the screen. The absurd grotesqueness of conversations and intimate interactions between impersonal dummies is heightened by moments where their modular body parts inexplicably become isolated and jumbled without any clear cause inside the dark void. Perspective cavalierly sweeps away as each scene fades and disappears in this looping video that repeats immediately upon completion.

In a particularly memorable vignette showing rows of dummies aimlessly tossing red balls back and forth, an individual that drops a ball but fails in its many attempts to pick it up serves as a poignant symbol of mechanization’s fallibility. Despite robotics’ advancement, absurd gaps remain in robots’ abilities where humans would have none. Such gaps often remain concealed, undiscovered until tragedy strikes, as with the many lives robbed by robotic car experiments. Lax’s crash dummies are timely metaphors for people reduced to disposable guinea pigs serving unseen powers.

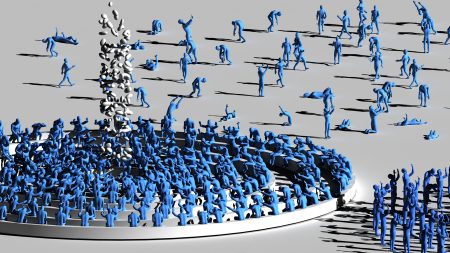

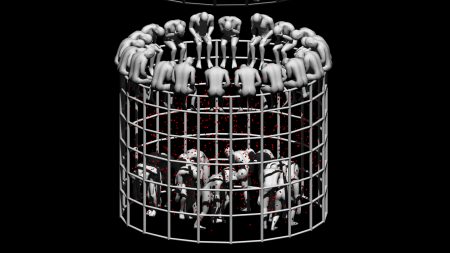

On a much grander scale, New Zealand artist Gregory Bennett’s looping videos also portray humanoids performing repetitive activities. As in Lax’s video, Bennett’s situations seem to develop on their own as though regulated by unseen forces. Whereas Lax focuses on small groups and zooms into robots’ absurd attempts at interpersonal relations, Bennett’s videos pan across sweeping architectural panoramas populated by legions of mannequins. Curated by Ari Lipkis, “Unbearable Infinite,” at AA|LA through Dec. 22, intriguingly juxtaposes three of Bennett’s videos with five etchings from 18th century printmaker Giovanni Battista Piranesi’s “Imaginary Prisons” series. Piranesi’s old-fashioned black-and-white dungeon-worlds meet their modern counterpart in Bennett’s 3D animations where flocks of homogenously blue, pink, red, or white mannequins enact mysterious ritualistic routines.

Are these stultified mannequins gesturing in worship to unseen gods, or have they simply taken leave of their senses? Whatever they are doing, Bennett’s figures appear mindless, devoid of individuality, acting only upon groupthink. In Exosphere (2018), choreographed squads mechanically flail about over spacious plazas, run in herds around curious machines, and gesticulate inside cages on strange staircases. Within these artificial environments, ersatz plants grow and mutate in machinelike conformity with mechanics of computer generation. The more you watch, the more disturbed you feel. In Panopticon 1 (2015), imprisoned mannequins exercise in small groups or alone within cells, sometimes lying prone and bound; buildings chaotically disintegrate and regenerate as if by mechanical magic, and people fall out of chambers in endless skyscrapers as though in mass suicide.

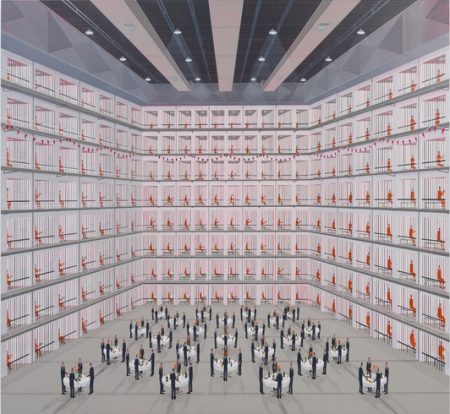

Resonating with Lax’s and Bennett’s video imagery, paintings in Ian Davis’ show, “2nd Dark Age,” which closed Nov. 17 at Night Gallery, depicted organized hordes of automatons in sterile environments. Pointedly emblematizing extreme class and power divisions, Conference (2018) portrays an elite party of similar suit-clad men standing at cocktail tables flanked by a tall, celled penitentiary wall full of prisoners appearing exactly alike in orange jumpsuits. Similar to Lax’s and Bennett’s looping videos, Davis’ repetitive compositions implicitly continue beyond his canvases’ edges; but as still images, his suggestions of infinite patterns seem starker; unlike the other two artists’ moving pictures, the only escape from his paintings is to look away, yet they remain reverberantly in your mind. Each artist’s work imparts empty impressions of stifling hopelessness.

Impersonal aspects of contemporary life are easily recognizable in the work of all three of these artists allegorizing the present through futuristic visions. Suggesting a “2nd Dark Age” having nearly arrived, Davis’ imagery appears most contemporary; while Lax’s and Bennett’s humanoids bring to mind “Singularity,” a popular techno-futurist theory promoted by Raymond Kurzweil and others, hypothesizing that artificial intelligence will someday lead to an exponential explosion of technological development triggering a “transhuman” or “post-human” era where humanity merges into machines with non-biological bodies. Though he has stated that such an epoch would be “neither utopian nor dystopian,”[3] Kurzweil certainly raves optimistically. Through their art, Davis, Lax, and Bennett suggest that a version of that future is already here, and it is certainly not utopian.

–Annabel Osberg

[1] “Jaron Lanier on fighting Big Tech’s ‘manipulation engine’,” John Thornhill, Financial Times, Jul. 6, 2018. https://www.ft.com/content/a3ea16f6-7edd-11e8-bc55-50daf11b720d

[2] “A vision of a very different L.A.,” Mimi Zeiger, Los Angeles Times, Nov. 25, 2018

[3] The Singularity is Near: When Humans Transcend Biology, Raymond Kurzweil, 2005.