Little need be said about the strangeness of 2020: A year inundated with historic events has brought to a standstill the customs and contact that once defined our lives. In March, as the reality of the pandemic set into Los Angeles, museums and galleries closed with the lockdowns, leaving in their wake a slew of shows to be canceled and postponed. Museums remain shuttered indefinitely; but for more commercial venues, the shows must go on. Most galleries have reopened by appointment with far fewer visitors, no opening fanfare, and plenty of masks and hand sanitizer. Some have found creative ways to present work online or in open public spaces. That many exhibitions are now on view is a comforting testament to the art world’s resilience. Yet the predominating appointment-only system severely restricts shows’ accessibility. If it continues beyond the pandemic—and at many galleries, it likely will—the art scene will revert to more exclusionary tendencies than ever. The need to secure an appointment discourages and potentially prohibits outsiders from seeing art, while forcing insiders to limit themselves to shows they already expect to like. For now, gone are the days of gallery-hopping, and with it, the thrill of serendipitously happening upon work one never would have guessed to be excellent. Nevertheless, in these trying times, it’s a relief to know that one can still see exhibitions in person. Of those I was able to visit this year, below are most noteworthy.

Rubén Ortiz Torres, “Plata o plomo o glitter”

Royale Projects

Responding to the “glitter revolution,” a movement that erupted in Mexico City in 2019 after demonstrators glitter-bombed the city’s security chief in outrage over a police officer’s rape of a teenage girl, Ortiz Torres’s sparkly paintings and embellished Tijuana police car parts offered powerful points of departure for considering the universal pervasiveness of police brutality and malfeasance. In retrospect, his show seems remarkably prescient: it opened in February, months before our own summer of protests.

Lisa Adams and Kelly McLane, “Unreality”

Pete & Susan Barrett Art Gallery at Santa Monica College

Adams’ and McLane’s dystopian depictions of conflicts among people and nature are punctuated by whimsical touches of humor and hope. Sadly, their all-too-timely show was only open for a few days before it was shuttered due to the lockdowns. Its title says it all: Each painter’s work brilliantly captures the unreal feeling of our present time.

Linda Stark, “Hearts”

David Kordansky Gallery

Indulging a tenor more heartsore than heartsome in her new body of work, Linda Stark disentangled her chosen symbol from its feel-good connotations of feminine affection and treacly approval, instead exploring its capacity for expressing more nuanced themes of mortality, pain, and grief. Her labor-intensive processes of dripping, embanking, and accreting oils over time confer her paintings with the gravity of devotional objects.

Caitlin Cherry, “Corps Sonore”

Luis De Jesus Los Angeles

Evoking a phantasmagorical nightclub populated by shimmering sirens, Cherry’s online show drew viewers into a deeper exploration of Black American women’s complicated roles in shaping, and being shaped by, popular culture in our computer-networked society. The inclusion of digital collages gave the imaginary world of her better-known paintings a whole new dimension onscreen.

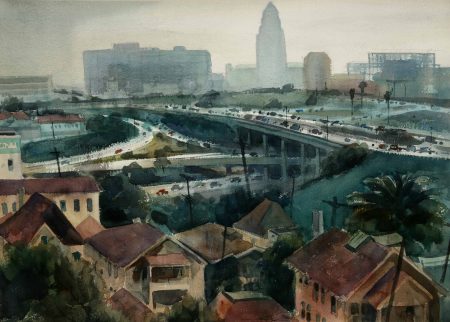

“Los Angeles Area Scene Paintings”

The Hilbert Museum of California Art at Chapman University

It’s often said that LA has a penchant for effacing its own history; but this exhibition attested to local artists’ determination to record in vibrant detail the city as they saw it. Over 70 paintings from the 1880s onward presented a sprawling survey of LA’s diverse districts and essences across time, offering a valuable opportunity for contemporary viewers to gain a better perspective on how the city has changed, and in what respects it has remained the same.

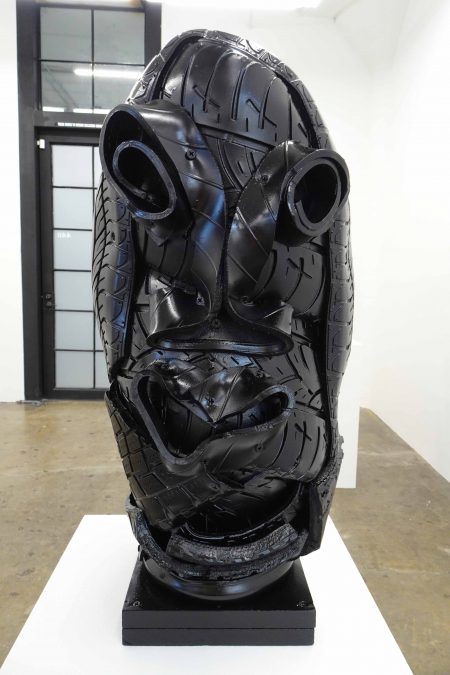

Kim Dacres, “Wisdom Embedded in the Treads”

Gavlak Gallery

Dacres’ bust sculptures were imbued with a weighty presence and spiritual poignancy akin to African tribal totems. So finely and expressively wrought were their features, it was hard to believe they were fashioned from discards found at roadsides and construction sites. The longer you gazed at each bust, the more it seemed to come to life. Her primary medium, tire rubber—a material associated with resilience and travel across long distances—spoke to diasporic migration, hard work, and the strength of Black communities.

“The Body, The Object, The Other”

Craft Contemporary

Despite its popularity in the mainstream art world, clay remains widely associated with craft. Rebutting that stereotype, this biennial featured technically outstanding, conceptually razor-sharp work by 21 contemporary artists exploring a wide variety of personal experiences and sociopolitical issues via the viscerally satisfying, age-old ceramic medium. Its title encompassed tripartite themes: the human body; historical art objects; and self-image in relation to notions of the Other.

Tania Franco Klein, “Proceed to the Route”

ROSEGALLERY

In Franco Klein’s staged photographs, which frequently recall Hitchcockian or Lynchian film stills, a sense of banality is permeated by the sense that something is terribly wrong. Her glamorous, weary protagonists are apt emblems for the increasing toll of everyday life in a society that devalues individuals while expecting them to perform.

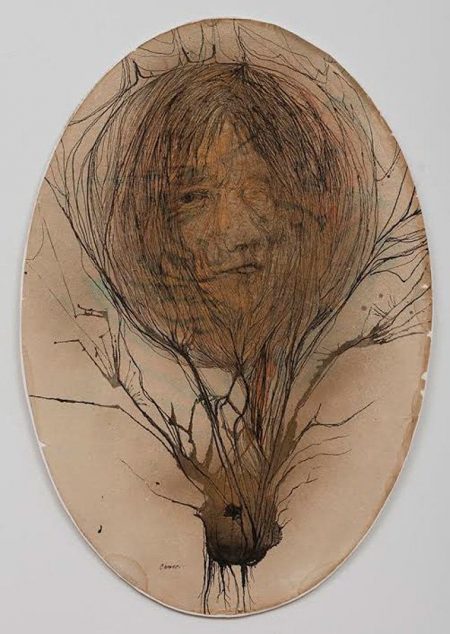

Cameron, “Madame X”

Marc Selwyn Fine Art

In life (1922-1995), Cameron’s art was often overshadowed by her colorful bohemian persona and her marriage to Jack Parsons; but decades after her death, her visionary work stands firmly on its own. Each of her drawings and paintings here exuded a bewitching intensity, conjuring up foreboding scenes of mysticism and metamorphosis.

“The Box Project”

Durón Gallery at SPARC (Social and Public Art Resource Center)

The pieces in this unconventional show were not created for public display; rather, they originated as part of a correspondence between three interconnected women’s collectives in Los Angeles, Mexico City, and Paris. Desiring to collaborate across borders in a manner that circumvented social media’s impersonality, they organized a postal exchange of individually boxed artworks, poems, and other items handmade by members of each group. Opened to a wider audience, the private nature and diminutive scale of the 76 artists’ works and stories conveyed a particular sincerity, provoking contemplation as to what gets shown, what remains unseen, and what is truly meaningful in a world saturated with flashing screens and depersonalized facades.

2021 will bring more vaccines and a new president. We can only hope that it will also include a return to something closer to normalcy.

–Annabel Osberg