“VOULKOS: The Breakthrough Years” at the Museum of Arts and Design (MAD) in New York City traces the evolution of Peter Voulkos from accomplished potter to one of the most—quite arguably the most—transformative clay artist of the 20th century.

The exhibition was co-curated by Glenn Adamson, former Nanette L. Laitman director of the Museum of Arts and Design; Andrew Perchuk, deputy director of the Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles; and Barbara Paris Gifford, assistant curator, MAD.

The exhibition is divided into six sections: “Early Works, 1953-1956; Pot Assemblages, 1956-1958; Painting and Sculpture, 1958-1959; Experiments in Color, 1960-1961; Process and Demonstration, 1961-1963,” and, following a gap of five years, the “Blackwares, 1968.” The sections suggest a linear artistic progression, so beloved by art historians, but rarely reflecting reality. I find some of the sections a bit forced.

Voulkos, the son of Greek immigrants, was born in 1924 in Bozeman, MT. He died of a heart attack in 2002, following a workshop at Bowling Green State University, OH. It seems a fitting end as Voulkos was renowned for his bombastic performances. In his classes, part of his shtick, according to his student Mary Heilmann, was to “throw a big form and step away from the wheel and he’d drop it on the floor. And then he’d make it into a pot.” 2

Like many who would become leaders of the contemporary craft movement in various mediums, Voulkos took advantage of the GI bill after serving as an armorer-gunner in WW II. He began his academic career at Montana State College, Bozeman (Bachelor of Science, 1951) and went on to the California College of Arts and Crafts, Oakland, for his MFA in 1952. At Bozeman, he majored in painting but a required clay course set him on his remarkable artistic journey. He became a skilled potter, gaining national recognition for his functional pieces.

“In considering how to install the show, the MAD exhibition design team took its inspiration from Voulkos himself, including the practice of creating work surfaces that sometimes doubled as exhibition pedestals (as in his exhibition at the Pasadena Art Museum in 1958) . . . . . and at the Primus-Stuart Gallery in 1961 . . . the environments he preferred to work in, and the concepts that informed his work.

“A gravel table is used to display Voulkos’s early work (seen here). It recalls a Japanese rock garden and, in turn, the 1952 visit of Shōji Hamada and Sōetsu Yanagi to the Archie Bray Foundation when Voulkos became aware of Japanese concepts in clay and Zen Buddhism as it relates to ceramic practice.” “A Word About the Exhibition Design,” Voulkos: The Breakthrough Years. London. 2016. Black Dog Publishing Limited, p. 188.

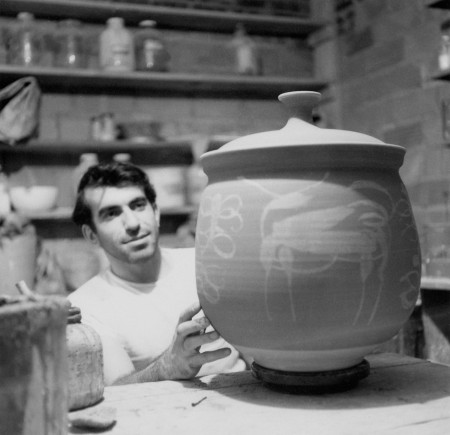

The first section of the exhibition focuses on Voulkos’s “Early Works, 1953-1956” as he moved away from his award-winning utilitarian pieces to more sculptural works. He began experimenting with surface decoration techniques. For example, he appropriated the technique of wax-resist from fabric dying.

In 1952 Voulkos and his fellow student Rudy Autio became the first resident artists at the Archie Bray Foundation for the Ceramic Arts in Helena, MT.3 There they met British potter Bernard Leach; Japanese potter Shōji Hamada; and Dr. Sōetsu Yanagi, founder and director, National Folk Museum of Japan. The trio was instrumental in introducing the Japanese aesthetic to the West. Through them Voulkos became acquainted with the asymmetry, abstract decoration, and serendipity of Japanese ceramics as well as Zen Buddhism.

A turning point in Voulkos’s artistic development occurred in 1953, when he taught a summer ceramics course at Black Mountain College in Asheville, NC. There he met M.C. Richards, American poet, potter and writer, who likely introduced him to Picasso’s work. Robert Rauschenberg, John Cage, Merce Cunningham, and poet Charles Olsen were also there. Richards and pianist David Tudor invited Voulkos to come to New York City where he met Willem de Kooning, Philip Guston, and Franz Kline, artists whose Abstract Expressionist paintings influenced Voulkos’s ceramic philosophy, leading most observers to attach “Abstract Expressionist” to his ceramic work. In Voulkos’s paintings the influence is painfully evident.

Voulkos’s definitive break with conventional ceramics can be seen in the second section of the exhibition: “Pot Assemblages—1956-58.” The name came from the sculptor John Mason, who met Voulkos in 1954 when he was studying at Chouinard Art Institute and they later shared a studio in Los Angeles. It describes the technique that Voulkos used for these pieces, slip-welding thrown elements, usually pounded out of shape, with slabs of clay.

The iconic work from this period is Rocking Pot, 1956. A wheel-thrown pot is presented upside down and is pierced with saber-like slabs. The compromised vessel sits on rockers that echo the airplane-like wing slab, balanced on top.

Voulkos is thumbing his nose at the pottery tradition. “According to the potter’s handbook, a vessel should function well. A cup should function well. A cup should hold liquid; a bowl or a plate, its contents; and these forms should sit gracefully on a flat surface,” as Barbara Paris Gifford wrote in the exhibition catalog. She continued, “Even the name is a thinly veiled gibe against the potter’s rule that properly made ceramics should never teeter. 4 Clearly Rocking Pot cannot do that.

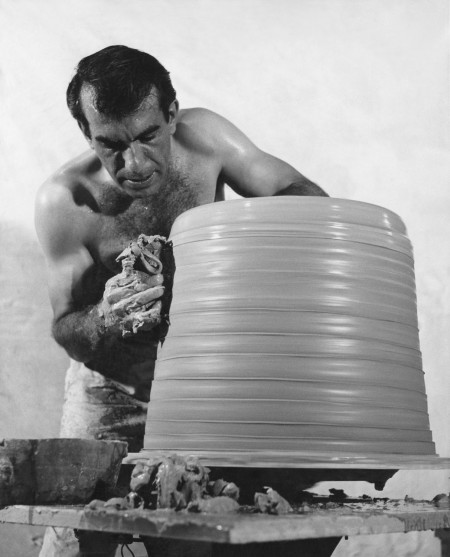

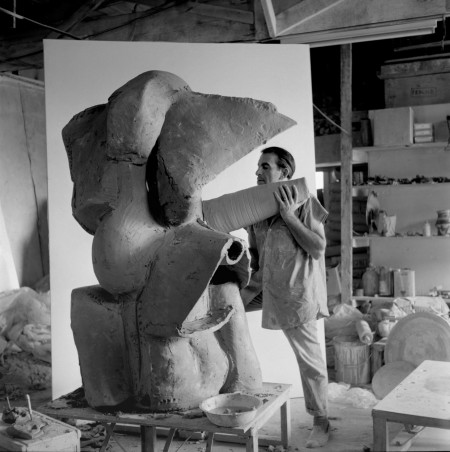

The “Painting and Sculpture, 1958-59” section seems particularly forced. In 1957, Voulkos and Mason set up a studio on Glendale Boulevard in Los Angeles, equipped with industrial-grade machinery 5 that would allow Voulkos to defy the size limits of the medium. Three imposing sculptures from this period—Sitting Bull, 1959, 65” high; Little Big Horn, 1959, 59 ½” high; and Tientos, 1959, 57” high—are on view.

Unlike more conventional ceramic sculpture, in addition to the vastly enlarged scale, Voulkos was not interested in achieving harmony among the individual parts. In the first two, the craggy shapes seem to be punching out of a central core while in Tientos, they looks as if they are melting.

There was also space in the Glendale studio for Voulkos to paint. I find Voulkos’s painting to be completely derivative–Abstract Expressionism a decade too late. Nonetheless Voukos saw value in the practice. He believed, “. . . the painting helped the sculpture, the sculpture helped the painting, pottery helped the sculpture and so they are interrelated, although they all demanded different disciplines and different forms of thinking.” 6

After Voulkos moved to a teaching post at the University of California, Berkeley, in 1959, he continued working in the Glendale Boulevard studio since there was no ceramics studio, which he was tasked to build.

The appointment was serendipitous since Voulkos had been fired from the Los Angeles County Art Institute (now known as Otis College of Art and Design) for what the director, Millard Sheets, called, “ivory-tower teaching.” 7 This charge seems odd given Voulkos’s pedagogy, which Paul Soldner explained in very different terms. “He didn’t lecture, he didn’t teach, he just worked.” 8

While Voulkos was putting together the clay studio in Berkeley, he joined Donald Haskin and Harold Paris to build a bronze-casting foundry. Voulkos found the medium well suited for the large commissions he was receiving at this time. Metal allowed him to contemplate the elements he had cast before combining them using the same assemblage technique that he had used in his clay work. The ceramist Jun Kaneko explained that Voulkos could “leave them for months around the studio, living with them in a casual way. Then something would tell him he was ready, and in one night he would assemble the whole piece.” 9

The fourth section–“Experiments in Color—1960-61”—highlighted a, fortunately brief, period, when the artist found another way to violate ceramic conventions. Rather than stick to the limited range of glazes available, Voulkos painted his sculptures after firing, which gave him complete control over color. Just as he was uninterested in harmony, as he played one form off against another in his assemblage method, his color was jarring.

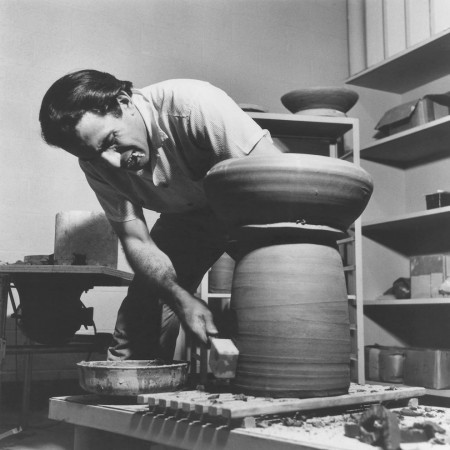

In the early ’60s when Voulkos was most involved with large-scale bronze commissions, much of his ceramic work came out of his energetic performances; the curators recognize this in the fifth section: “Process and Demonstration, 1961-63.”

At this time Voulkos was doing at least six demonstrations a year, mostly in New York City. At Greenwich House Pottery in 1961, he made Josephine. An unnamed observer remembered how the artist “worked with total abandon and total focus at the same time.” Voulkos himself said, “The quicker I work, the better I work. If I start thinking and planning, I start contriving and designing. I work mostly by gut feeling.” 10

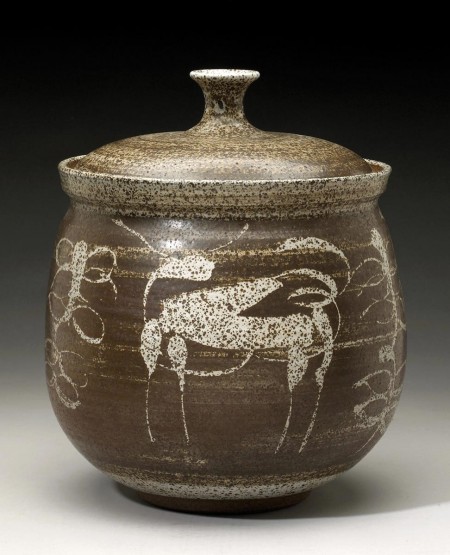

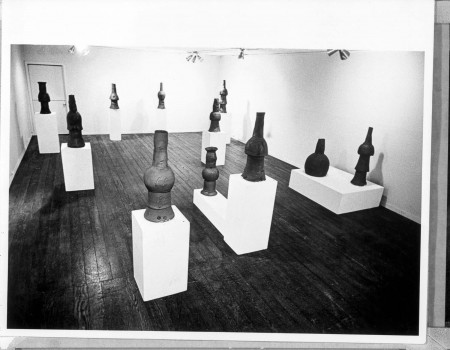

The “Blackwares, 1968,” mark the dividing line between his first explorations in clay and his mature work. He was 44 when he showed this body of work– tall vases, later called “stacks,” and plates–at Ruth Braunstein’s Quay Gallery in San Francisco in 1968. The forms are the closest he’s come to traditional shapes in the previous 15 years. These plus jar-like “ice buckets” and tea bowls became his formal vocabulary for the rest of his life.

He covered the vessel-like forms in an iron-based slip, giving them a dark metallic effect and their name. Black was intended to eliminate anything that might detract from the form. I wonder if Rauschenberg’s “black paintings,” started in 1951 at Black Mountain College, might have had some influence on these pots.

Adamson argues that the blackwares “emphatically reestablished the core value of pottery to Voulkos’s practice.” 11

In Voulkos’ mature work, not seen here, in addition to returning to more traditional forms, albeit altered and even violated, he began firing his work in a wood-fired anagama 12 kiln, a technique with a venerable heritage. Dating back to the fifth century in Japan, the wood-fired kiln imparted subtle coloration to his stoneware forms.

Voulkos rebelled against ceramic traditions, but he never rejected it as his mature work affirms.

–Karen S. Chambers

“VOULKOS: The Breakthrough Years,” Museum of Arts and Design, 2 Columbus Circle, New York City, NY 10019. 212-299-7777, madmuseum.org. Tues.-Sun., 10:00 am-6:00 pm; Thurs. and Fri., 10:00 am -9:00 pm; closed Mon. and major holidays. Admission: General: $16; Seniors: $14; Students: $12; Members: free; 18 and under: free. (This does not include groups). Group Rate (8 or more): $12. All groups must make reservations, including during Pay-What-You-Wish hours. KLM Thurs., 6:00 pm-9:00 pm: pay-what-you-wish. Exhibition through March 15, 2017.

FOOTNOTES

1 Rose Slivka quoted in wall text, Section Four: “Experiments in Color, 1960-61.”

2 Mary Heilman quoted in wall text, Section Four: “Experiments in Color, 1960-61.”

3 Brickmaker Archie Bray founded the Archie Bray Foundation in Helena, MT, in 1951 with the aim of making it “a place to make available for all who are seriously interested in any of the branches of ceramic arts, a fine place to work.” Archie Bray Foundation, website.

4 Barbara Paris Gifford, “Thrown and Painted: The Exhibition Plates,” Voulkos: The Breakthrough Years. London. 2016. Black Dog Publishing Limited, p. 136.

5 Ceramic engineer Mike Kalan built what was the largest updraft reduction kiln outside a factory setting—6 1/2’ x 6’ x4’. They installed large humidifiers used in Southern California fruit industry to keep the clay from drying out. The two artists bought a commercial dough mixer to mix large amounts of a clay body formulated by Voulkos. It combined two different clays mixed with sand and grog to have high workability and lamination that made it possible to achieve the size Voulkos was aiming for as he continued his practice of combining forms that characterized his “Pot Assemblages.”

6 Voulkos interviewed by B. Horiuchi, unpaginated. Glenn Adamson, “Back to Black,” footnote 35. Voulkos: The Breakthrough Years. London. 2016. Black Dog Publishing Limited, p. 136.

7 “Given this remark, we can surmise that he perceived Voulkos’s practice to be elitist; a rejection of the vessel tradition, which threatened the order of skill-building, one of the tenets of ceramics. As a so-called utilitarian discipline, postwar ceramics had initially been aimed at returning veterans, young men accustomed to hard work, performing the manual labor required by their chosen, hands-on medium.” Jenni Sorkin, “Gender and Rupture,” Voulkos: The Breakthrough Years. London. 2016. Black Dog Publishing Limited, p. 15.

8 Andrew Perchuk, “Out Of Clay,” Voulkos: The Breakthrough Years. London. 2016. Black Dog Publishing Limited, p. 33.

9 Adamson, “Back to Black,” Voulkos: The Breakthrough Years. London. 2016. Black Dog Publishing Limited, p. 69.

10 Gifford, op. cit., p. 169.

11 Adamson, op. cit., p. 83.

12 The wood-burning anagama kiln came to Japan from China via Korea in the fifth century. It requires continuous stoking with wood for firing, which may take a week or more and that long to cool down enough to empty it. During the firing, the burning wood produces ash, which settles on the pieces and with the complex interaction of flame, ash, and the minerals of the clay produces a natural ash glaze. This produces a wide variation in color, texture, and thickness, ranging from smooth and glossy to rough and sharp depending on the heat and location of the forms placed in the long kiln. A skilled artisan can anticipate the results but nothing is certain. For the remainder of his life, Voulkos worked with Peter Callas, himself a well-known potter, to fire his work.