The Fotofocus Biennial 2016 features a marvelous array of photography exhibitions – eight exhibits curated by Kevin Moore for Fotofocus and about sixty additional ancillary exhibits of photography that various museums, galleries and libraries from Cincinnati to Columbus have prepared in support of the biennial endeavor.

While the eight exhibitions specially selected by the curator naturally feature contemporary photography, a number of institutions participating in the photography biennial looked back in time to the early days of photography in the 19th century when camera equipment was loaded onto horses or mules and photographers traveled “the road less taken.” I will focus on three items: two exhibitions: Picturing the West: Masterworks of 19th-Century Landscape Photography at the Taft Museum and Islands of the Blest at the Mercantile Library downtown and a special panel at the Cincinnati Art Museum: Artist-Led Communities: Meatyard, Lyons, Siskind & Callahan.

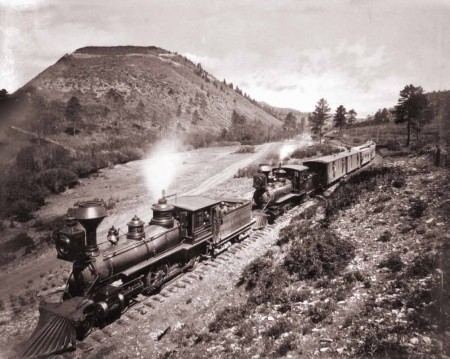

I liken our appreciation of and response to 19th century photography to the popular appreciation of Impressionist paintings. Who doesn’t love Monet? The early photographers were working in the same time period and were facing and benefitting from the same advances in technology. Artists are of their time. Monet painted the railroad station in Paris, all hard iron and rising steam, while William Henry Jackson (American, 1843-1942) photographed the railroads as they snaked their way throughout the West. Jackson’s Station of the Rio Grande Western, Salt Lake City, Utah Territory is a perfect example of this interplay between the awe-inspiring feat of laying railroad track in nearly inaccessible mountain terrain and the irretrievable scarring of the land. The exhibition takes note of this fact by encouraging visitors to see the Taft’s sad painting, The Song of the Talking Wire, by Henry Farny. An American Indian leans against a telephone pole in a wintry, desolate landscape.

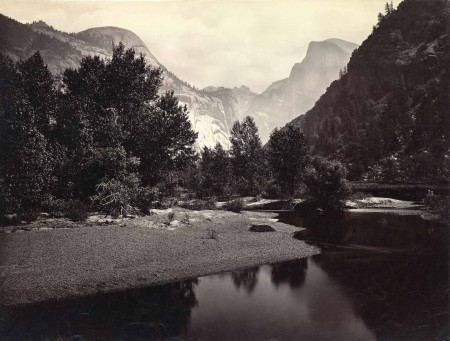

Yet it is the land that is so breathtakingly showcased in this exhibition by ten-renowned 19th century American and one British photographer. The exhibition begins naturally with photographs of the Eastern United States and gradually moves westward. Niagara Falls is featured. Thomas H. Johnson made thirty-two mammoth plate views of industrial sites along the Delaware and Hudson Canal and Gravity Railroad. Mammoth plate negatives are 18 x 22 inches and provide breathtaking detail. The negative and the resulting photographic print are the same size so no detail is lost. Imagine the weight and effort to keep these glass plates intact in the wilderness, especially out West, until they could be brought back to the cities to be processed. The exhibition alone is worth seeing for the mammoth plate photographs of Johnson, Carleton Watkins, Charles Bierstadt (brother to landscape painter Albert), Eadward Muybridge (wonderful to see his dreamy wilderness photographs here), William Henry Jackson, Frank Jay Haynes and Charles R. Savage. One dramatic photograph of the Midwest is featured: Henry Hamilton Bennett’s Up from the Mouth of the Canyon, the Dells, Wisconsin of 1890, then the exhibition moves on to capture the wildness of the West. The Taft notes, “The public craved images of America’s untamed territory, and intrepid photographers showed them what the rugged land looked like. They captured natural wonders, such as sweeping canyons and plunging waterfalls, and manmade marvels like railways and mining structures as well.” All forty photographs are from the collection of Michael Mattis and Judith Hochberg of New York with Tamara Muente of the Taft as the installation curator.

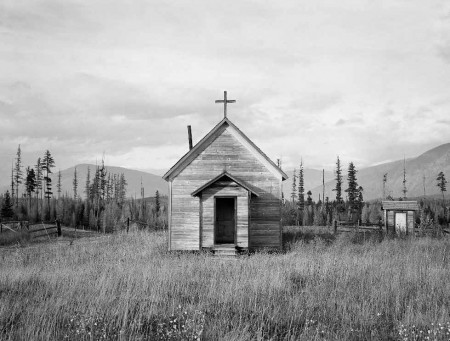

Cincinnati Art Museum’s Brian Sholis co-curated the Mercantile Library’s exhibition, Islands of the Blest along with Bryan Schutmaat and Ashlyn Davis. John Faherty, director of The Mercantile Library, was integral to the development and organization of this exhibition. The exhibition shares its title with Schutmaat’s and Davis’s book of the same name (Island of the Blest, edited by Bryan Schutmaat & Ashlyn Davis, Silas Finch, 2014). The title is drawn from a poem by Michael McGriff, which also appears in the book. The curators went through thousands of photographs from the Library of Congress and the U.S. Geological Survey. Presented are twenty-seven rare photographs from 1871 to 1943, some never exhibited before. Known and unknown photographers are featured showing gold prospectors, mines, mining towns seen close up or from the vantage point of a mountain above. These photographs are often raw, since their purpose was pure document. There is a greater emphasis on fact over grandeur. The hard work of poling large logs downstream is evident in Russell Lee’s Tilamook, Oregon and W.C. Mendenhall’s Wapitas Lake, Kittitas County, Washington shows the rugged tents of a work camp. This makes for exciting slices of life. It is no surprise that among two of the later photographs, from 1939, are two photographs by Dorthea Lange who is known for her poignant images of migrant workers: Migrant Farm Worker, Merrill, Klamath County, Oregon and Boundary County, Idaho.

This leads to a to rumination on the power of color. Photographs in these two exhibitions are black and white, or numerous shades of dark sepia brown, or silvery grays or purple-black. Nineteenth century chemicals and processes allowed for this range within black and white photographs. We are nostalgic when we see the warm-toned photographs of our long-dead relatives. There is a memorial quality to such photographs and such colors. The associations are natural. There is, as a result of this quality, the death of the wilderness contained within these landscape photographs and it cannot be escaped. I believe it is how we should read them.

There is also the graphic pull of black and white, whether in photography, drawing, printmaking or painting. Why is this? Once our world was less colored. Darkness crept in by late afternoon. Cave or cottage or castle was lit by firelight or gaslight. Shadows, outlines of figures, details were all in monochrome or nearly so. The dawn is not in full-blown Toys R Us colors. The black of trees and buildings and telephone poles shift as the pale light of dawn brings color back into our worlds. The monochrome in art triggers these associations etched in our evolutionary memory. A photograph by its nature is a memento mori.

Numerous lectures and panels add depth to the Fotofocus Biennial exhibitions. “Artist-Led Communities: Meatyard, Lyons, Siskind & Callahan” was a panel discussion conceived by Brian Sholis of the CAM to shed light on the backstory to the museum’s exhibition Kentucky Renaissance which is also reviewed by Aeqai. It was a rich panel discussion focusing on the strong friendships, support and collaborations among the early 20th century fine arts photography pioneers. I doubt few who attended went away having only learned a little. I think everyone learned a lot and the passion of the panelists –Brian Sholis, Elizabeth Siegel of the Art Institute of Chicago and Jessica McDonald of the Harry Ransom Center in Texas – solidified the importance of artists supporting artists, of forming artists’ communities. This was especially crucial to photographers.

We forget that after the first strong wave of documentary photography, such as in the exhibitions at the Taft and Mercantile, photography, like the other arts, entered a period of intense experimentation, investigation and doubt. Cubism, Surrealism, Abstract Expressionism all arose from experimentation, investigation and doubt. Mid-twentieth century photographers had to fight for space in fine arts departments. Photo labs were tucked away in science or communications department labs. No one knew what fine arts curriculum in photography should be. Nathan Lyons was the hero in the role of advancing fine arts photography from his vantage point in Rochester, New York, home to Kodak. Add Beaumont Newhall and Minor White and Rochester was the center for fine arts photography.

In Chicago, the Institute of Design was the center for photographic development. Founded by Bauhaus émigrés, it was ‘the new Bauhaus.” Lazlo Maholy Nagy was a founding member. People who would become icons of mid-century photography taught there: Arthur Siegel, Harry Callahan, and Aaron Siskind.

In Kentucky, little known to those outside of photography, was the Camera Club of Lexington, started by Ralph Eugene Meatyard and Van Deren Coke in Lexington, Kentucky. Along with like-minded photo enthusiasts, most of whom had technical jobs in photography by day, Meatyard and Coke reached out to poet Jonathan Williams and writers like Guy Davenport, Thomas Merten and Wendell Berry. There was a rich climate of experimentation across artistic fields here. The exhibition, Kentucky Renaissance, is a real tribute to these passionate and visionary leaders in photography and this exhibit runs through January 1, 2017 at the Cincinnati Art Museum.

Picturing the West: Masterworks of 19th-Century Landscape Photography

Taft Museum, October 22, 2016–January 15, 2017 | Fifth Third Gallery

Tuesday-Sunday 11 a.m-4p.m.

Saturday and Sunday: 11 a.m.-5 p.m.

Islands of the Blest

Mercantile Library, through November 18, 2016.

Monday, Tuesday, Thursday, Friday: 9 a.m.-5:30 p.m.

Wednesdays: 9 a.m. to 7:30 p.m.

Saturdays: 10 a.m. to 3 p.m.

Fotofocus Biennial

Maryellen Goeke, Executive Director

Fotofocusbiennial.org – for information on exhibitions some of which continue through

January, 2017.

Cynthia Kukla is an artist, emerita professor and art critic who just returned to

N. Kentucky from the flat fields of Illinois

I enjoyed your clear analysis of the photography of the 19th Century as its photographers were documenting the westward expansions of the United States. Even though the pictures are black and white with tones of gray they show the beauty of the land and the efforts of the settlers to build something out of it.

A very interesting read of an art and time little appreciated by most people now. Makes me wish I could get there to see the exhibitions personally, but your presentation gives me a good perspective of the event as well as the history depicted there. Well done.

Cynthis, seems you’re doing well and…retired?

Well written on a worthy subject but one and a half caveats. I don’t take death of the wildnerness out of any of this. Change, sure, but there’s plenty of wilderness both in the western regions and, increasingly, in the East as cities get denser and marginal lands revert to ever-wilder ecologies.

In point of fact, didn’t the early photographers take developing materials and equipment with them on expeditions? I thought I recall reading that such was part of why it was so cumbersome. Perhaps the printing was done in the cities. Worth another look? Eager to be corrected.

Best to your family, Mark J Carr

Very insightful analysis. Only a painter could identify many of the deeper qualities of the photographs, even those unintended by early generation of photographers who would be more archivist than artist. And black and white is never going to disappear–digital cameras have apps, and digital platforms have options for converting from color.

Cynthia you are an amazing and inspiring woman! This article is very well written, and poetic. You taught me to write and poetry is not an easy task. So, for you to have me understand this and to want to read more, is just plain poetry. That is not easy. I had to look up a few words even though i have a MFA, so great work on the intellectual side as well. My criticism to you (because you were a huge part in me dialing in my writing) is to be more vocal. I want to read more, girl! I want to see this side of you. i was most interested in the color history. It made so much sense. More, more,more, :).

It was very rewarding to cover the two photography exhibitions during Fotofocus. Painting and photography have always had a dialog with each other, since the invention and expansion of photographic processes. I find it important to put any art gesture into its larger context and appreciate Dr. Hansen’s observations on the interplay between the two mediums. I greatly appreciate the thoughtful commentary from colleagues from as far away as San Francisco and the corrective remark that photographers usually developed the plates on site.

A marvelous command of Western Photographic art of the 19th Century. Excellent lay-person appeal, too. (“Who doesn’t like Monet?”)I hadn’t heard of the “Meatyard.” Of course, we have Railyard art venues and museums in both Santa Fe and Albuquerque.