The Riffe Gallery’s “Women to Watch Ohio – 2018” exhibit highlights ten female Ohio artists working in metal. The show was inspired by the selection of four Ohio artists shortlisted for the exhibition “Heavy Metal”, the National Museum of Women in the Arts’ (NMWA) Women to Watch biennial. Reto Thuring, Curator of Contemporary Art at the Cleveland Museum of Art and Matt Distel, Curator and Exhibition Director at the Carnegie in Covington, KY selected Carmel Buckley, Tracy Featherstone, Llewelynn Fletcher, and Leila Khoury (the finalist for the national show). Distel and Columbus curator Ann Bremner completed the Riffe exhibit’s roster with six additional artists.

In the case of both exhibitions, curators sought to expand prevailing ideas about metal sculpture, highlighting works that, according to the NMWA exhibition statement, “disrupt the predominantly male-dominated narrative that surrounds metalworking”. During Ohio’s industrial past, as for that of many Rust Belt states, metals such as iron and steel were ubiquitous materials. Generations of factory workers, machinists, and other industrial laborers developed considerable skill with metal through their work. After World War II, the steel and iron factory materials and industrial aesthetic migrated, along with American soldiers benefiting from exposure to European avant-garde art and the GI Bill, to the university art departments and the art studios. By the mid-twentieth century, a new, mostly male generation of sculptors began experimenting with casting iron and welding steel to craft abstract and non-objective works. Their art spoke an industrial language and expressed the formal fascination of modernism that resulted in an aesthetic of monumental geometric and totemic objects.

However, women artists have also been developing a rich narrative of their own around metal work. In Cincinnati, Patricia Renick is renowned not only for her monumental fiberglass and steel works, but also for organizing the landmark 1987 national conference honoring women sculptors, including pioneering artist Louise Nevelson, who translated her iconic reclaimed wood sculptures into monumental welded steel constructions. Since midcentury, we have also seen Louise Bourgeois’ cast phalluses, cells, and giant spiders, Gego’s delicate, complex wire constructions, Lee Bontecou’s gaping, wall-mounted holes with taut canvas and steel over protruding armatures, Ruth Asawa’s suspended woven sculptures inspired by Mexican women’s crafts, and Diana Al-Hadid’s fragile steel rod and plaster architectures, to name just a few. In each case metal is a critical material for that artist, serving a conceptual purpose complemented by her ingenuity and skill in handling the material.

The idea of women working in metal is not a revelation but a continuum with a history that includes many divergent paths. The Riffe Gallery’s exhibition provides a glimpse down several of these. While the show is anchored by works made with steel, iron, bronze, aluminum, copper, silver, and lead, it is ultimately shaped by the mettle behind the work rather than the metal in it. Both curatorial essays express this sentiment. Bremner’s essay underscores, “As (co-curator) Matt Distel points out in his essay, this exhibition “is about more than a material,” and its strength comes not from metal but from artists.” The artists in the exhibition have fluently incorporated metal into their creative language, expressing diverse personal, social and political as well as formal concerns. As a result, steel totems have been exchanged for aesthetics of feminism, environmentalism, and social justice, made visible by material, pattern, scale and process.

Initially the show has a whimsical feel to it. Tracy Featherstone’s bright, wall mounted Paper Rug: Pink Ghost, made of small strips of painted cut paper and aluminum, recalls the Pac-Man character Pinky, and Kelly Malec-Kosak’s Hard/Soft, a series of stuffed vinyl and sterling silver pendants in irregular shapes rest like little balloons against the wall. The variety of ways metal is used throughout the show – shaved, found, cast, cut, welded, plated, hammered, patinated, filed, enameled, taped, bent, and encased – inspires close looking and comparison.

Like Paper Rug: Pink Ghost, many of the works use metal as a component integrated with other, sometimes surprising, materials that indicate an irreverent regard for its Modernist-era heft and purity. Featherstone’s Brief Moment of Cultivation, composed of ceramic, copper plating, nylon, and grass displayed under an intense purple grow light, combines organic and inorganic matter into a sci-fi form resembling a giant metastasized plant/machine hybrid seed. Susan R. Ewing’s Momento Mori Series: Form with Fungus (Blackening Polypore) delicately incorporates jagged pieces of rusted steel into a mass of bronze, graphite and mica powder, and epoxy steel, to create an equally organic-looking, otherworldly object.

Image courtesy the artist.

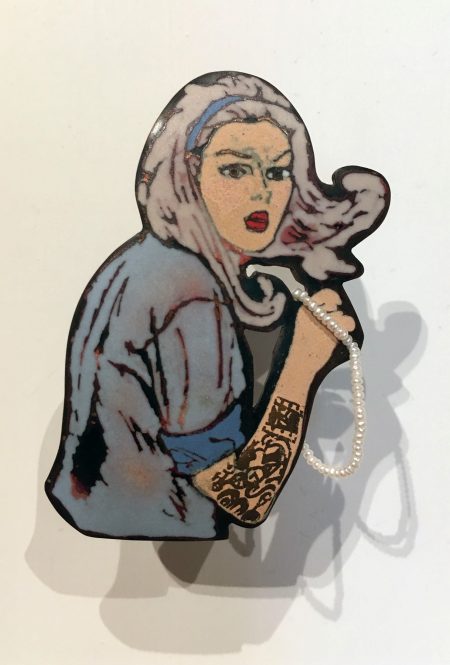

Works in the exhibition include both the monumental and the miniature. Ewing’s Prague Star Series pieces, from 1997 and later, traverse that entire scope from a jewelry concept that evolved, through studies and maquettes, into a monumental sculpture, StarSphere 2010, located on the campus of Kent State University. Kelly Malec-Kosak’s brooches in Shaped Space, although individually small, as grouped together feel expansive in their references to architecture and pattern design. Marissa Saneholtz miniaturizes the miniature by crafting tiny 3-D jewelry on palm-sized female portrait brooches. The portraits, derived from 1950’s and 60’s teen romance comics, incorporate the addition of tattoos to become contemporary statements on female agency, as in The traditions were hers to change. Carmel Buckley’s Untitled, (2018) consists of multiple castings of bronze, aluminum, and steel heads, in human and miniature scale, carefully arranged around a seesaw. Here the confluence of proportion, materials, and composition suggest themes of imbalance and disparity.

Image credit Susan Byrnes.

Image courtesy the artist.

Patterns and structures of meaning are more central to the pieces in this exhibition than wrestling with weight and mass, heat and flame to produce a work of art. In Olga Ziemska’s large outdoor sculptures (depicted as photographs) Mind’s Eye and I’m watching you, watching me, watching you, metal plays a supporting role. Ziemska’s works are constructed with metal armatures concealed by cut stacks of reclaimed trees. The various sizes of round wood end grains combined with large openings designed into the centers of the sculptures provide a play of intricate patterning in the positive space, with a shifting landscape view through the negative space, creating awareness of human perception of and interaction with the natural environment. In Llewelynn Fletcher’s (made in collaboration with Amanda Curreri) Shield for Queer Kin: Protection, welded steel tubing becomes an asymmetrical armature across which a fabric barrier of Sashiko patterned embroidery is stretched. Behind the barrier is a carved wooden fist making a gesture called the “fig” sign, which in some cultures is a protection from the evil eye, while in others is an offensive gesture that references female genitalia. Carol Borham-Hayes’ sprawling cast concrete and reclaimed metal conduit objects Exsanguinate and Eviscerate provide an anthropomorphic appeal, but their names provoke violent images, connecting body and building as sensitive organs. These works set the stage for Leila Khoury’s piece, Aleppo Bathhouse (Fragment). Khoury’s minimalist steel structure displays cast concrete tiles recalling Khoury’s Syrian heritage and the painful destruction of Syrian culture happening as a result of war.

These artists employ a variety of strategies from solo production to collaboration or hiring fabricators and using technological tools to create the ideas they envision. In another of Fletcher’s works, Steel Feather Shield, identical plasma cut metal feathers are technologically made, and then hand formed and patinated. Mary Jo Bole trained in ceramics, but to create Goodbye and Goodbye, Victorians, made of cast iron, and chrome and nickel-plated cast iron, respectively, she worked with artisans to complete works to her specifications, a process she often undertakes. Her pieces explore Victorian-era funerary objects of impermanence contrasted by their transformation into iron, a more permanent material that will also eventually erode and decay. Metal exists only as a reference in Buckley’s Untitled series of drawings created from graphite rubbings of cast manhole covers, embellished with silver acrylic marker.

Image courtesy the artist.

These ten “Women to Watch” continue to shape the contemporary metalworking narrative, each on her own distinct path. The works as a whole demonstrate an adventurous commingling of mundane and specialized materials; mass produced, appropriated, and unique objects and images; and technological and traditional handcrafted processes. Yet from ecology to pop culture to war, each artist has created a larger context for her work from patterns of meaning both historical and current in the process of exploring a material with significant cultural weight.