On view at the David Kordansky Gallery through October 21, 2023

Shara Hughes’s vivid paintings in “Light The Dark” sprawl across spacious canvases, to generate otherworldly imaginations of the natural world. Formally they might recall works by French Impressionists or, occasionally, abstract impressionism. These works also feel contemporary. Some of them are imbued with an almost neon feeling hue that might recall, if you’re like me, the ever-creeping works generated by AI. Of course, these are much better. Their brightness, as the title of the exhibition might suggest, seems to revivify traditions of landscape painting in a time when human relationships to the natural work are not so bright. Hughes uses subtle paint strokes to occasionally raise the occasional plant or deluge of water in each painting, largely letting the colors speak for themselves. She uses dye and oil to fill the backgrounds, which provide a subtle foundation for the sharper details that populate the canvas. In totality, the exhibition operates on a dual register. It presents detailed depictions of environments, and it generates an otherworldly aura to expand our sense of time and space in relation to the natural world.

Oil, acrylic, and dye on canvas

Diptych, overall:

72 x 174 inches

(183 x 442 cm)

(Image#: SHU 23.020)

Photo: JSP Art Photography, courtesy of David Kordansky Gallery

Swelling lies somewhere in the middle of the range from abstraction to detail. It sets a tone, aesthetically and theoretically, for the rest of the work. Dark blue and purple waves rip across two large canvases. They curl upward like tentacles. The waves at the very bottom are simple and thin, while those above are thick and imposing. Above those are smaller, thinner strokes of varying colors. If the painting were gazed upon upside down, one might think it depicts an explosion, giving way to billowing, ominous smoke. Swelling mines a unique setting that contrasts the other landscapes. Most of the others are landlocked. When water is present it typically flows through material land. Here, though, Hughes depicts a primarily fluvial scene. These tentacular waves, perhaps of connective ocean, remind me of Donna Haraway’s “tentacular thinking.”

For Haraway “tentacular thinking” models the interconnected methods of thinking (and artmaking) required for responding to our environmentally complex time. For her it is a matter of genre. In her case SF is of great importance. SF’s tentacles include, “speculative fabulation, science fiction, science fact, speculative feminism” (Staying With the Trouble, 31). For me “tentacular thinking” is required for seeing the interconnections of literature, painting, photography, and the natural world, among other forces. Swelling establishes the tentacular, fluvial heart of the exhibition, connecting the varying landscapes of mountains and meadows that populate the gallery walls. These pieces harness a speculative energy that depicts familiar spaces in new ways, rendering waves, flowers, trees, and mountains into fantastic, seemingly otherworldly beings. They are scenes that seem to stretch beyond the spatial and linear temporal boundaries of the human era. Fortunately, they are this-worldly, but the artist vividly interprets what might seem ordinary to many people.

Oil, acrylic, and dye on canvas

115 x 72 inches

(292.1 x 182.9 cm)

(Image#: SHU 23.022)

Photo: JSP Art Photography, courtesy of David Kordansky Gallery

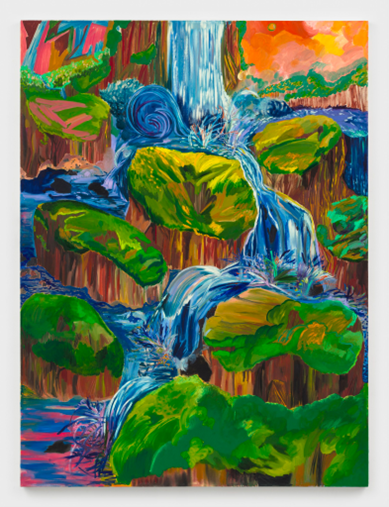

Swelling embodies dynamic nature. The swirls of the waves guide movement across the canvases, some of which can be deceptive. One might look at a painting like The Hangdog and see a static landscape, which would miss the movement of the central wilting plant or the light rising along leaves as the sun rises. Tumble captures the tension between movement and static. Bright waters weave down around mossy rocks. Tension is presented here as part of the natural DNA of the landscape. The water isn’t bothered, moving keenly to the next temporary resting place. Of course, the rocks will erode over deep periods of time as the water cycle repeats this tumbling. Take note of the water that swirls in the top left quadrant of the painting. This motion alludes to the spiraling movement of the grander life of water as it moves back and forth between atmosphere and surface.

Oil, acrylic, and dye on canvas

96 x 72 inches

(243.8 x 182.9 cm)

(Image#: SHU 23.021)

Photo: JSP Art Photography, courtesy of David Kordansky Gallery

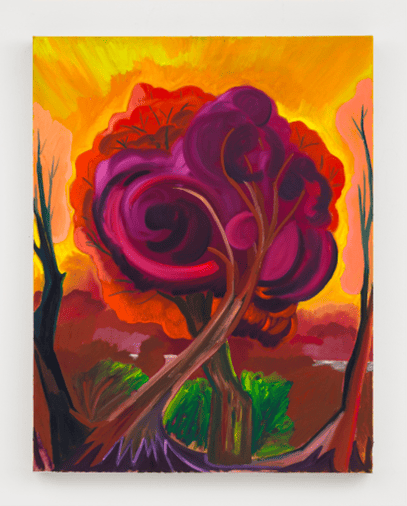

Hughes activates movement with her lines. There are crisp and unbent lines and there are curved and swirling lines. I was attracted to the swirls, which are more prevalent in some pieces than others. Even when they are subtle—such as the swirling water in Tumble—they provide important pieces to the painterly cosmic equations. The Kiss centers swirling flowers while Trust and Love centers a deeply hued tree. The swirls of each painting obscure the details of petals or leaves—this is particularly the case for the latter painting. These swirls provide an absorbing depth. They draw the eye directly into the varying centers yet resist fixing the gaze of the viewer at one point. The other sides of those centers might open up toward an unknown continuity beyond the canvas—both artistic form and the natural world move through the painting as two concepts that exist beyond the skill of the artist to resist totalizing visions of what the natural world should be for human perception. The swirls remind me of black holes, which collapse linear uniformity in spacetime and confound human understanding of the cosmos.

Oil, acrylic, and dye on canvas

36 x 28 inches

(91.4 x 71.1 cm)

(Image#: SHU 23.014)

Photo: JSP Art Photography, courtesy of David Kordansky Gallery

Fool Me Once, is, perhaps what one finds inside the swirls. Hughes’s lines bend and contort while the damper background colors blend into each other. There are more swirls here and, given the context of Hughes’s other paintings, we can assume they are flowers scrawling across a chaotic landscape. If one were to observe the painting independently, though, they might read other shapes and figures in Hughes’s deepest foray into abstraction. The painting hammers down an otherworldly interpretation of a chaotic natural world that, independent of human life, bustles across its own myriad spectrums. The lines that wobble across the canvas remind me again of Haraway’s “tentacles.” Perhaps they are the tentacles that bind the seemingly disparate artistic styles of more traditional landscape painting and abstract impressionism. Perhaps they are the tentacles that remind us that human life and other-than-human spaces are intertwined. Or perhaps they remind us of the destructive, inevitable force of the black hole that operates on deep time scales independent of human comprehension.

Oil and acrylic on canvas

86 x 78 inches

(218.4 x 198.1 cm)

(Image#: SHU 23.016)

Photo: JSP Art Photography, courtesy of David Kordansky Gallery