Born in Florence, Italy in 1935, Forti immigrated to Los Angeles in 1939 with her Jewish parents. While at Reed College in Portland, Oregon, she met the artist Robert Morris to whom she was married from 1955 to 1962. Although Morris is recognized for having contributed to minimal art, land art, process art, and post-minimal art, Forti’s oeuvre is less known even though her nine “Dance Constructions” (1960-1961) indubitably influenced his practice, especially his notorious 1971 Tate Gallery exhibition that closed after 4 days, but was “reprised” in its entirety in 2009 at Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall.

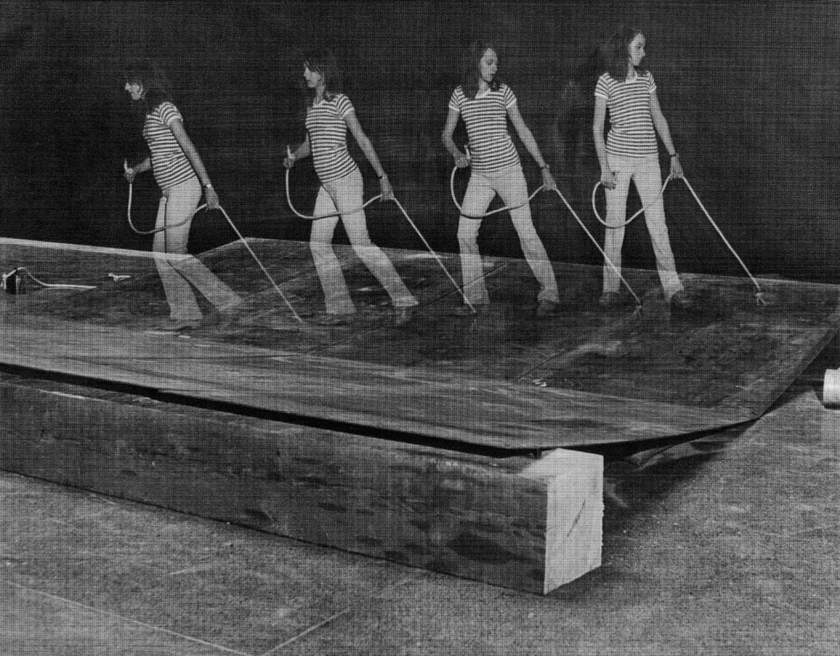

Morris’s 1971 participatory objects totally echo her earlier “Dance Constructions,” two of which premiered in “New Happenings at the Reuben Gallery” (1960) in New York City, months before Allan Kaprow presented Yard in “Environments, Situations, Spaces” (1961) at Martha Jackson Gallery. An early example of participatory art, Yard, which consists of piles of old tires scattered about a courtyard, can evade participation; whereas Forti’s living sculptures require performers. During “New Happenings,” Forti activated Rollers, square, wooden wagons, while Robert Morris and Yvonne Rainer moved atop Forti’s SeeSaw (both 1960), an ordinary wooden plank teetering across a saw horse. In 1961, Forti presented “Five Dance Constructions & Some Other Things,” organized by La Monte Young at Yoko Ono’s loft. In 2015, MoMA acquired nine of her “Dance Constructions,” which are among MoMA’s most requested artworks to show.

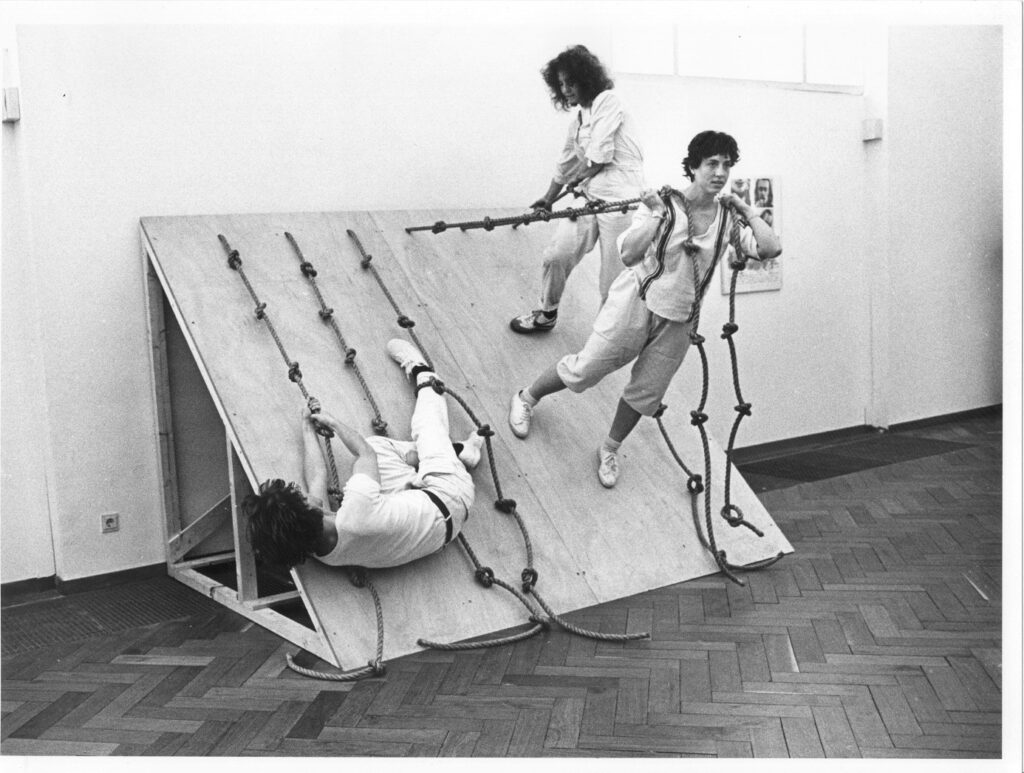

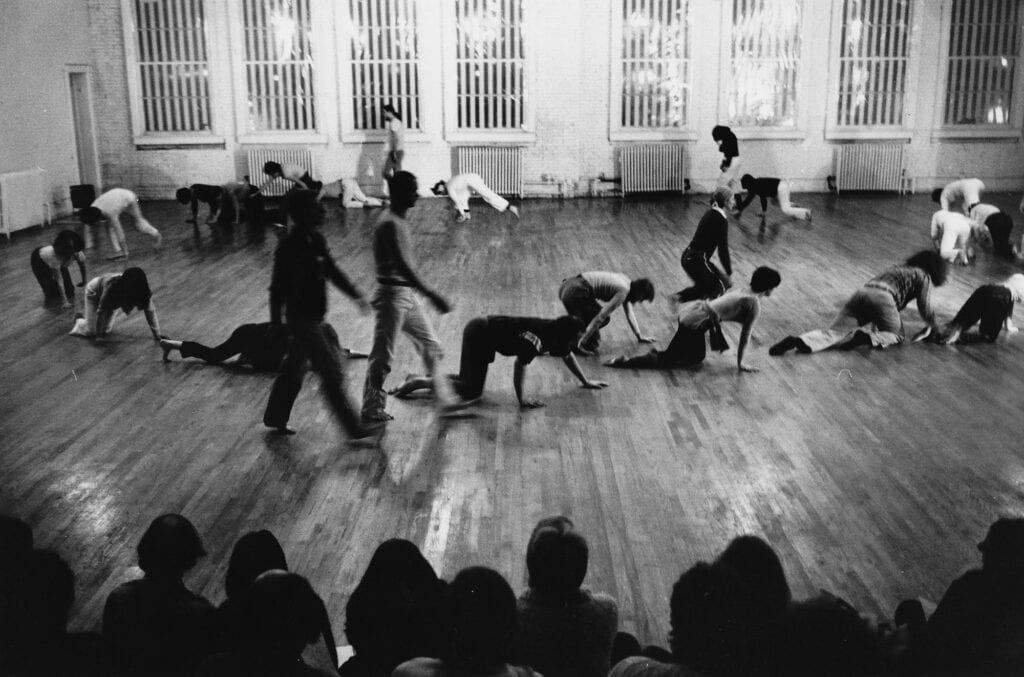

In 1960, Forti and dancer/filmmaker Rainer apprenticed with San Francisco dance company of Anna Halprin, with whom Forti had danced since 1955. Although Forti didn’t perform at Judson Memorial Church, dancers associated with Judson Dance Theater (1962-1964) have credited her influence. In Rainer’s memoir Feeling are Facts, she identifies “Simone [as] the inspiration and the fountainhead….I don’t know what her intent was, but for me what she did brought the god-like image of the dancer down to human scale more effectively than anything I had seen.” Forti’s MOCA survey invited visitors to experience performances of three of her nine “Dance Constructions,” Huddle, Slant Board, and Hangers (all 1961/2023), as well as a 32’ video featuring four different performances of Huddle (1974-2011).

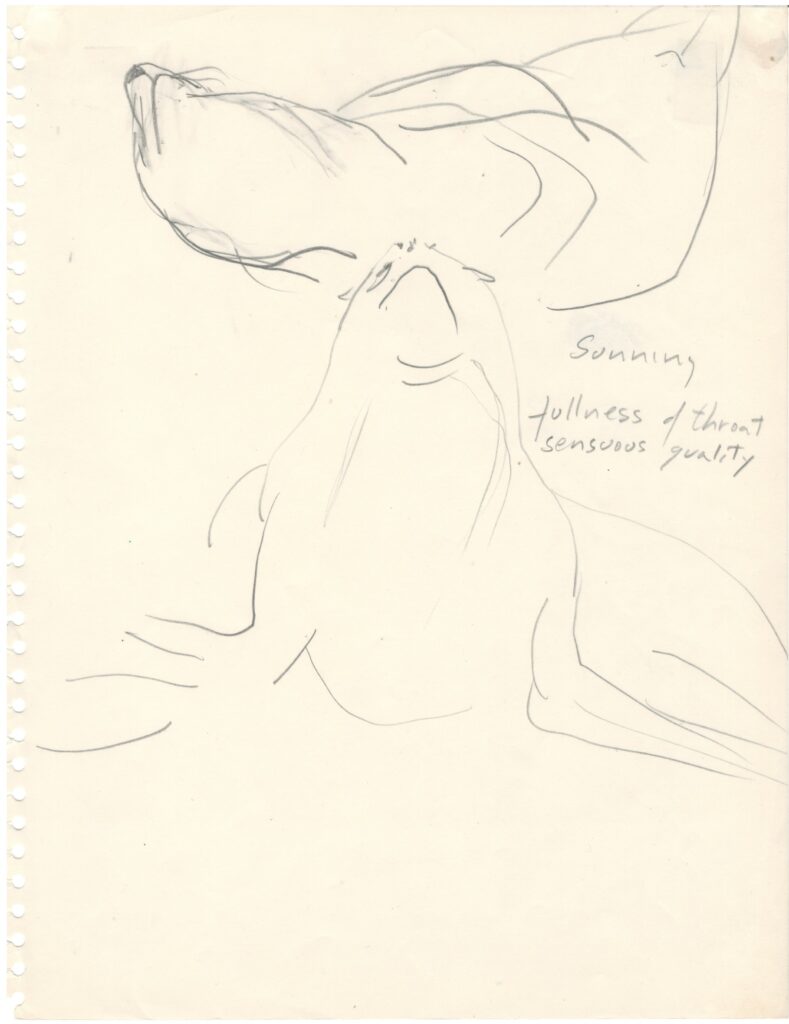

Additionally, Forti’s survey featured scores of drawings, some seemingly associated with her working out performers’ positions, and others recording animal movements. Several of her studies of sunning sea lions (1968), an “important” turtle (1970), a goose shaking water off tail feathers (1973), a grizzly turning a corner (1974), an elephant sensing with its trunk (1982), and a polar bear reaching for its nose (1982), appear to have inspired live performances.

During the pandemic, Forti created Figure Bag Drawings (2020) for which acrylic figures lie prone, horizontally strewn across several brown paper bags. Her Large Illumination Drawings (1972) and related performance announcements appear to double as choreographic scores.

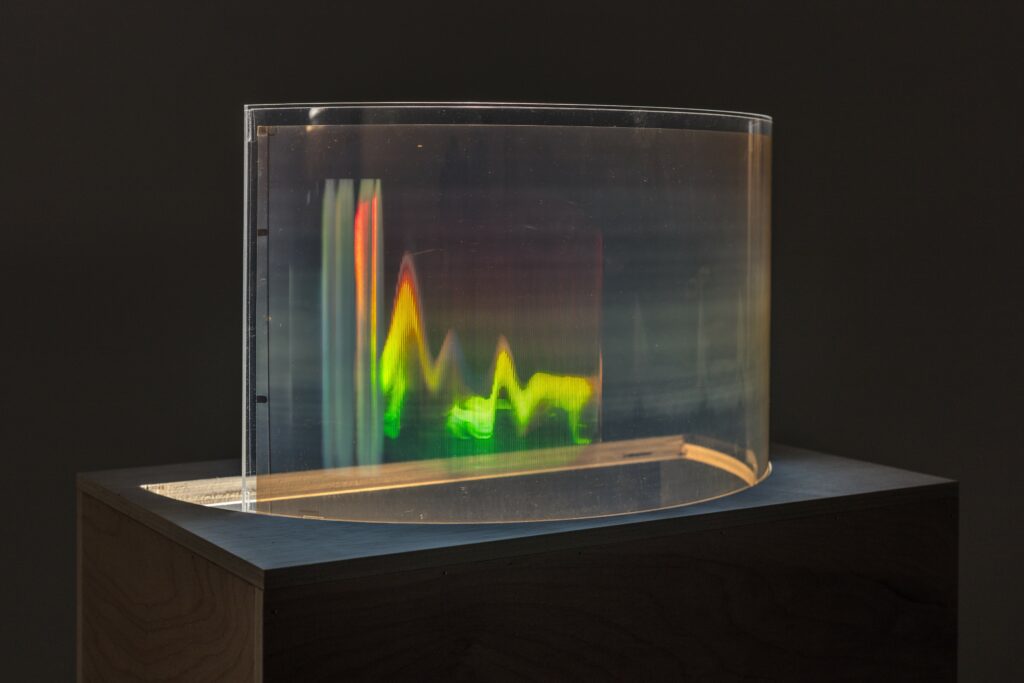

In addition to drawings, Forti’s survey included an oil painting (1960), five note books (1970-1977), three holograms (1975-1978), the vinyl record Illuminations (2010) created in collaboration with Charlemagne Palestine (2010), nine videos (performance documentations), dozens of silver gelatin prints (performance documentations), a horn made from metal tubing (2012), and Ai Di La (2018), a CD whose nine recordings dated 1961-1984 vividly capture her use of voice, folk songs, handmade instruments, and physical space. Additionally, there was plenty of ephemera, including posters, invitations, brochures, fliers, and her 1974 book Handbook in Motion. Hardly afraid of language, drawings such as News Animation-Words Solid (2012) pay tribute to her various performances inspired by news headlines, which she performed as early as 1986.

Although the term “physical dance” is primarily associated with the choreographer Elizabeth Streb, Forti’s “Dance Constructions” are no less physical. Since each is based on a “written instruction,” much like Fluxus “event scores” such as Alison Knowles’ Make a Salad (1962), which debuted at London’s ICA in 1962; they might seem easily performable. Hardly a matter of following instructions, achieving what MoMA curators call “body-to-body transmission,” a unique way of “thinking, learning and activating,” requires several full days of instruction followed by even more days of rehearsal with Sarah Swenson, the principal stager of Forti’s movements. In her hands, movement is passed on, not unlike ancient Japanese crafts that people learn in order to recreate ancient objects, rather than restore them.

Although the dance community has had little qualms about embracing Forti as one of their own, the visual artworld has been comparably hesitant, even though her “dances” based on “event scores” began as happenings, an antecedent to “performance art.” She self-identifies as an artist who “works with movement, using her own body alongside other materials and media.” Typically choreographed for several performers, her “performances” eschew the singular performer familiar to the performance art genre. It matters little whether one categorizes her “Dance Constructions” as dance or performance art, since they clearly influenced both fields.Around the time Rollers and SeeSaw premiered at the Reuben Gallery, Robert Whitman, one of Kaprow’s students, shocked the artworld with his experimental theater piece American Moon (1960), inspired by space travel. More visual than traditional theater, American Moon privileged “plastic construction” over storytelling. Forti not only participated in this theater piece alongside Lucas Samaras, but she married Whitman two years later. In 1966, Whitman worked with Robert Rauschenberg and Bell Labs engineer Billy Kluver, which led to Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.), an organization that paired male artists with male engineers (“guys who do stuff”). A decade later, Forti married tech-oriented musician Peter Van Riper, who suggested she work with Lloyd Cross with whom she made holograms. Amazingly, her holograms Bug Jump (1975-1978) and Striding Crawling (1978) appear to capture animal movements.